Jack (and Jill) Be Nimble: An Interview with Mary Cash and Jason Low

In between the few huge publishing houses and the many tiny ones lie the small independents.

In between the few huge publishing houses and the many tiny ones lie the small independents. Mary Cash is vice president and editor in chief of Holiday House, founded by Vernon Ives in 1935 and currently publishing sixty-plus new books a year; Jason Low is the publisher of Lee & Low Books, co-founded by his father Tom Low and by Philip Lee in 1991 and publishing approximately twenty books annually. I met with Mary and Jason in New York soon after Hurricane Sandy, and after some discussion about what the weather had wrought on all of the city’s publishers, we got down to talking about what the current climate is like for the littler guys.

In between the few huge publishing houses and the many tiny ones lie the small independents. Mary Cash is vice president and editor in chief of Holiday House, founded by Vernon Ives in 1935 and currently publishing sixty-plus new books a year; Jason Low is the publisher of Lee & Low Books, co-founded by his father Tom Low and by Philip Lee in 1991 and publishing approximately twenty books annually. I met with Mary and Jason in New York soon after Hurricane Sandy, and after some discussion about what the weather had wrought on all of the city’s publishers, we got down to talking about what the current climate is like for the littler guys.Roger Sutton: Are you conscious of working as an independent publisher?

Mary Cash: Definitely. I used to work for what was at the time the largest publishing conglomerate in the world (what is now Random House; then it was Bantam Doubleday Dell), so I think about it every single day. At Holiday House we aren’t beholden to either shareholders or owners who are not accessible to us, or to a group of executives that are charged with making us all behave or making sure that we’re profitable.

Jason Low: The independent thing is pretty huge at Lee & Low, too. I’ve been in the publishing business for fifteen years, but I haven’t had any other type of experience — I’ve only known it this way. I work with my brother and my dad — it’s a small group of people, and there’s no red tape. Essentially, we get together, jointly make a decision, and then go from there. It’s incredibly challenging to run a small publishing company. Publishing is going through such changes — just to be in the business at this time is really interesting.

RS: Mary, at Bantam Doubleday Dell, you would have had an elaborate acquisition process, which I’m guessing is only more elaborate there now, in which several levels of approval would be required…

MC: …and paperwork that had to be filed before you could even make an offer. You had to do an entire research project! I was so used to this method that when I first got to Holiday House, for the first book I wanted to acquire, I went into John Briggs’s office, and I had my reviews, my sales figures, all about the author, how many awards she’d won, all kinds of things that I’m rambling on and on about, and John’s looking more and more confused. Finally he stopped me and said, “Mary, what about the book?” That is a big, big difference.

RS: Sales are just as important to small publishers as big publishers, but I’m guessing the scale is different.

JL: For us, it’s just that everything’s smaller. Print runs are smaller. Our expectations are smaller. We’re very realistic. If we can cover the initial investment, everything else is gravy. It frees us up to take a lot of risks, and we do. And really, there are a lot of risks, in terms of what we acquire. Because many of the things that we go after are, for instance, biographies of people you’ve never heard of.

RS: Like that guy with the motorcycles — Honda. I loved that book.

JL: Before we did Honda, I didn’t even know there was such a person; I just thought it was the name of a car company. What I like about that book is the universal theme of “follow your dreams.” Honda wasn’t a good student; he was terrible, in fact. But he was good with his hands, with machinery. I think that’s an important message to give to kids. You have your different things you’re really good at—it may not be school, but hey, look at this guy. Honda’s a great example of a project we might go after.

RS: And how does that work at Lee & Low? If an editor brings in a project, what does he or she have to go through in order to get that book approved for publication?

JL: The owners are all in the room — we all read everything that we’re going to acquire. And then the editors, and that’s it. We really just go by the notion that nobody has a crystal ball in terms of what’s going to be successful, so you’ve got to go with your gut. If the people in the room feel strongly about this manuscript, then we’re going to give it a shot.

MC: And so many things can change between acquisition and publication. At a big publishing house, you have to jump through hoops if you discover that a thirty-two-page book needs to be, say, a forty-eight-page book. And there’s always tension if you want to alter the specs, because it was not what was approved of or signed off on. And you’re signing up books two to five years before you publish them, and so many things can change in that time. Including the technology.

JL: We’ve seen a lot of change in technology. But I feel that it doesn’t speed up the process of making books, because the illustrations are still dealt with by archaic media. We’re still dealing with paintbrushes and paint, stuff people have been using for ages. And then you plan for a book to take six months to a year, but then, you know, illustrators — how often do they run into personal problems that basically make that fall down?

RS: Like sleeping late.

JL: Exactly. So more often than not I see books become multi-year projects. It’s not uncommon. I think publishing’s a very odd industry in that way. Economically it doesn’t make a lot of sense. It’s really based on this creative process that’s very old.

RS: So do you feel then you have more — I can’t remember what the latest business-world buzzword is for “flexibility.” Oh, yes, we must be “nimble.” You can easily say, “Okay, this isn’t going to be on spring 2014. We can put it on this list.” Or can you speed something up?

MC: We can do both. Although it’s easier to put things off than speed them up. In all of our decisions, as at Lee & Low, the decision-making process is completely streamlined. I always tell people I can get an answer right away, whether it’s the answer I want or not. It’s like the difference between trying to turn a small sailboat, which takes some thought and some skill, and trying to turn a gigantic ocean liner, where you’ve got to get hundreds of people working together. We can turn on a dime.

JL: We’ve had to do that many, many times over the years.

RS: Do you find that being smaller and more agile can work to your benefit with authors and agents?

MC: Definitely. For one thing, our contract is much easier to read. And agents do send us a lot of new people, too, because it’s easier for us to take on new talent. We don’t have to come up with a whole marketing strategy to sell the project to the publishing board.

JL: We work with a lot of new people, too. Part of Lee & Low’s original mission was to develop new talent, so that was the idea from the get-go. It lightens the negotiating of it — sometimes authors or illustrators are unagented, but if they are, they can’t really ask for the moon, and we can’t go there anyway. And large advances are just not possible. Our big thing is that our books stay in print a very long time, because we don’t publish many, and we can really pay attention to every single book that we are putting out. That’s something that agents like to hear, and authors like to hear it, too. They say, Well, I want to go with these guys even though I’m not going to get everything I asked for. And from an owner’s point of view, I know how much we’ve invested in this thing — time, money, everybody’s effort — so for me, I don’t want to see any books go out of print. I have a personal as well as monetary stake in this. I’ve got a lot of skin in the game, you know? So it definitely motivates us to try really hard on everything.

RS: One way that your companies think very differently from each other is in terms of audience. Mary, Holiday House is trying to reach traditional groups — schools, libraries, bookstores, general readers; basically the same people that Random House and Macmillan are trying to reach. Jason, your company has more of a mission: to bring multicultural books of all kinds, written by all kinds of people, to different channels. Mary, how does it feel to be the little fish in that big pond?

MC: It feels good. I have a huge amount of independence, which I would certainly not have at a larger publisher. And we still have our niches that we fit into.

RS: Holiday books.

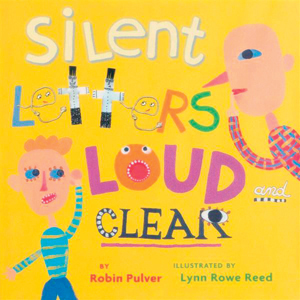

MC: Yes, and holidays that aren’t necessarily big holidays to other publishers, like Groundhog Day and St. Patrick’s Day. We’re very attuned to what’s happening in schools, so we also do wacky grammar books and irreverent math books that still teach math, and I think these are areas that a larger publisher would not be as interested in. Because to pay for their overhead, they’ve got to sell a lot more copies than we do.

RS: And that’s something that’s true of both your companies — you really have an investment in the school and library market. Most of the Big Six publishers don’t depend on it.

JL: We made that decision many years ago. When I first entered the business, we worked with both the trade and the institutional market. But it seemed to me that the institutional market was the one that was embracing what we were doing. At that point I asked the question, “What kind of publisher are we?” We realized that, really, our strength was institutional sales. We went whole-hog and basically never turned back.

RS: But, like Holiday House, it’s trade books for the institutional market.

JL: Yes.

MC: Once librarians and teachers embrace a particular book or a particular author, it’s far more likely that it will have a longer shelf life. Because when a teacher starts to use it, when it’s part of the program, or when he sees that this book works well with a certain kind of kid, then he hangs onto it. It becomes part of his teaching.

JL: Yeah, it gets referred to kids year after year after year: the strength of the backlist.

RS: Mary, what do you miss most about big publishing? The deep pockets?

MC: The deep pockets are not available all the time, to everyone. They’re only available for specific kinds of things, and they weren’t necessarily the sorts of books that I was doing. I really can’t say that I miss that. Daily life is just so different. I spend much more time editing books. With a big corporation, communication is like this constant obstacle, and you spend much of your time doing presentations so that people in the company know what you’re doing, writing memos and reports, traveling to sales conferences in other places, having lots and lots of meetings. It’s so much more pleasant to be working on the books, with other editors, with the art director, calling up authors, having illustrators come in with their dummies. It’s a lot more fun than sitting in a meeting.

JL: All that stuff takes time away from what people are supposed to be doing. It takes time to put together a presentation. It takes time to do anything, really. If you were to run a timesheet on the things you do every day, even the simplest thing takes up your time.

RS: Jason, you’re an independent publishing baby. I mean, this is really all that you’ve known. When you see your opposite numbers at conferences, what do you envy about their situations?

JL: I do like, when I’m at an ALA conference or someplace, to see them building their towers [of giveaway ARCs].

MC: That’s the only thing I want, too. I want their booths.

JL: We just started a YA imprint — science fiction, fantasy, and mystery — and we’ve published two books. We’re just beginning to get those types of books, so my pathetic towers look nothing like their towers. I don’t have that many to give away, so my tower’s a bitty tower. We’ve just started asking: How are we going to get this new imprint’s books noticed on such a small scale? And I guess the social media stuff is going to come into play. But even that has its limitations, because you’re tooting your own horn to the people who are already following you. You’ve got to go out and try to get more people to subscribe, and that ain’t easy.

RS: So you both contend with big publishers. And now we have all these new self-publishers, digital publishers, or print-on-demand publishers. Do you keep your eye on that side of things?

MC: I would say not in a concerted way. I pay some attention, but there’s just so much out there. And I think that is the real disadvantage to being a self-publisher: there is so much out there. How on earth are you going to get any attention?

JL: It’s like the whole scheme of what’s being published anyway: there’s going to be good and there’s going to be bad. The only thing I take offense at is the co-opting of the “indie” label. These self-publishing guys are trying to take it for themselves, and I’m not willing to give it up to them.

RS: Are you ever presented with a book that you love, but you think is not right for Holiday House, or not right for Lee & Low?

MC: All the time. Certain formats we can’t do — novelty books, board books. Which creates a bit of a problem if you have an artist who wants to branch out into those areas. We don’t have the right kind of distribution for those sorts of things. We can’t get a book into Walmart or discount drugstores, or the kind of places where that sort of book needs to sell.

RS: Why couldn’t you get a book into Walmart, say?

MC: First of all, Walmart doesn’t even want to see your products if you don’t have a critical mass. And big bestsellers. If you’re Random House, you go in there and say, Oh, I have all these cookbooks by Rachael Ray. Don’t you want those? And then you can get some other books in there as well. We don’t publish on a mass market schedule, either, where you’re really publishing every month. We have two lists a year, still. And that’s very old-school.

JL: We would probably have to avoid something that required a very large advance, so that would rule out a lot of high-profile authors and illustrators. We avoid things like, say, a book about Martin Luther King, because how many Martin Luther King books are already out there? What new spin would we bring to that? But we would do something about John Lewis, who was MLK’s right-hand man.

RS: What does the news that Random House and Penguin are getting together mean for your companies?

MC: After a certain point of big, it doesn’t matter to someone like us anymore. I don’t think we’re going to be affected by the fact that they have merged, because we aren’t competing with them in the same ways that the other big publishers are.

JL: We’re also not looking at the big guys as competitors, really. They’re almost in a different universe than we are. We’re a small universe. We do our own thing. We run the company as best we can. We try to do right by everybody who works with us, people working for us, the authors, the illustrators, and that’s our world. That’s all we’re focused on. Yes, we’re trying to predict like everybody else what’s happening with the digital stuff, but nobody knows that yet. I would have to say we’re definitely playing more follower than leader in that respect.

MC: And the leaders, I don’t think know where they’re going.

JL: Well, that’s the thing. Everybody’s driving and the headlights are out, basically.

RS: Given you don’t have the big pockets, how do you keep the authors and agents coming?

MC: I have to say, at Holiday House, our authors have been really wonderful and loyal to us, and I think there are some people who will always prefer to work with the smaller publishers. Some will want a huge one, but just like we’re not the answer for everyone, the big publishers aren’t the answer for everyone, either.

JL: We’ve started a lot of careers, and now and then those people end up moving on, but I will say that a lot of them do come back, like Greg Christie, for instance. We published his first book, and he does publish with many different houses, but he does come back, and he says it’s because he really likes working with us. We work with Ted and Betsy Lewin as well. They’re Caldecott honorees and all that, and they publish with us now because a) they like the experience, but b) the stuff they want to do in some of their books, the big houses aren’t interested in. It doesn’t matter that they’re the Lewins. They like to do these travel books, based on their adventures, and we think they’re great, so we will do that for them. There are people who are loyal. I think that if they didn’t have a good experience — obviously we earn their loyalty in some way in return.

MC: Yeah, good or bad, I think it is a very different experience.

RS: What is the next step for Holiday House and for Lee & Low? How are the next twenty years looking?

MC: I think smaller publishers are going to be, in a way, better equipped going into the future because of our small overheads. I don’t know that print publishing — because it is going to shrink — will be able to support the infrastructure of a large company.

JL: I think for us it’s just keep doing what we’re doing. We’ve found a way to be profitable, doing the kind of books that we do. Our mission has definitely dictated that, but it has also grown and shifted to encompass a lot of the things that are coming up in today’s modern world. People know to come to us for multicultural books; now we also address issues including sexuality, same-sex parents, disabilities, autism. We brought out a book about a deaf baseball player. So I think that gives us even more places to go, in terms of the stories we want to tell. I’m happy with that.

From the March/April 2013 issue of The Horn Book Magazine.

RELATED

RECOMMENDED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!

Roger Sutton

http://archive.hbook.com/magazine/editorials/jul99.aspPosted : Mar 22, 2013 06:54

Roger Sutton

Oh thanks, E. "ARTIST-HATER ALSO ACCUSES PLEASANT COMPANY OF PEDDLING CHILD PORNOGRAPHY"Posted : Mar 22, 2013 06:53

Elizabeth Law

I also appreciate Barbara Johansen Newman's comment. Illustrators *have* sometimes been treated as stepchildren in our business , or at least they've often been professionally overshadowed by writers, who have loud voices. At the same time, what I've taken away from the long exchange above is "Gee, you must be new here. This is the many-decades-outspoken Roger Sutton speaking, guys." And hey, Roger, isn't it time to run another link to your American Girl editorial?Posted : Mar 22, 2013 06:48

Roger Sutton

Christine, you're right about "partner." I used "client" because that is how I have heard illustrators refer to publishers, but your term better reflects the nature of the relationship. In the article, I made a joke about why illustrators might be late. In the comments here, i amplified that joke to observe that all contributors to the publishing partnership are capable of being late, and that their reasons for being so are not always the best. While I don't see the obligation to apologize for any of these remarks, i do take Barbara's point about illustrators feeling like step-children, which I do understand and have sympathy with. I'll only say that ninety-some years of the Horn Book Magazine should prove that we are on your side.Posted : Mar 22, 2013 06:17

Barbara Johansen Newman

I think it is important to remember that illustrators have felt like the step children in the industry for long time. Let's not forget how long it took to get that "I" added to SCBW. Ironic, since you can't have picture books without pictures. Can you blame any of us for having feathers that are easily ruffled? I've been illustrating for 30 years, the last 15 of which have been of-by-for-and-about children's books. I've had to beg for a little (and I do mean little) more time because of delayed sketch comments, changes in text, or highly detailed artwork that required extra attention in spite of 12 hour days and 7 day work weeks. And once in a blue moon, the realities of real life intervene. But, damn! Never even thought of the "I need to sleep in" approach. I shudder to think of how many extra zzzz's I might have had. Who knew?Posted : Mar 22, 2013 06:02