Beatrix Potter in Letters

by Bertha E.

"'Here’s peppermints for you, Pig-wig! Here's peppermints for you.' Pig-wig is you, Allan, and I've got peppermints at home for you." So spoke my grandnephew, Arnold, aged four years, as he came running out onto my sleeping porch, one morning this week, with the little friend who was going to spend the day with him. A week earlier he had sat up on my bed, leaned against the pillows and studied the pictures as I read to him The Tale of Pigling Bland. When the story was finished, he was given the book as a belated valentine and had taken it home where it had been read to him every day. Now he spoke in the words of it.

A few weeks earlier he had come in chanting:

Four-and-twenty tailors

Went to catch a snail,

The best man amongst them

Durst not touch her tail;

She put out her horns

Like a little kyloe cow,

Run, tailors, run! or she'll have you all e'en now!

When I asked him what he was singing, he said, "Why, don't you know? That's what the mice sang when Simpkin peeked through the keyhole.''

"Oh, you mean in The Tailor of Gloucester."

"Yes, and the mice finished all the lovely coat 'cept just one single cherry buttonhole, and they left a little note. The note said, 'No more twist.' "

William and Bertha Miller with their grand-newphew, Arnold Manthorne

William and Bertha Miller with their grand-newphew, Arnold ManthorneIn how many homes in the British Isles and America are childish voices speaking today, as any day in the last forty years, as my small grandnephew spoke, and thereby making immortal the author-artist, Beatrix Potter.

The news of her death on December 22, 1943, has brought to me a sense of deep personal loss. I never met her, but since the spring of 1927 letters have come from her several times a year, always giving clear, direct expression of her vigorous and salty personality; showing her thorough understanding of the changing world, with its increasingly disturbing events, and revealing gradually her own special interests and varied gifts.

When the war was upon England in all its violence her courage never failed, but she turned then more than ever to her hobbies as relief, or "escape" — a "modern" use of this last word she did not like but used, perhaps, because the need for relief was so great. Her last letter, received in November, 1943, spoke of her having been upstairs for a long time with bronchitis and the need to save strain on a heart which had never been normal since an attack of rheumatic fever as a young woman, and closed characteristically with the words, "But I hope to do a bit more active work yet — and anyhow I have survived to see Hitler beaten beyond recovery."

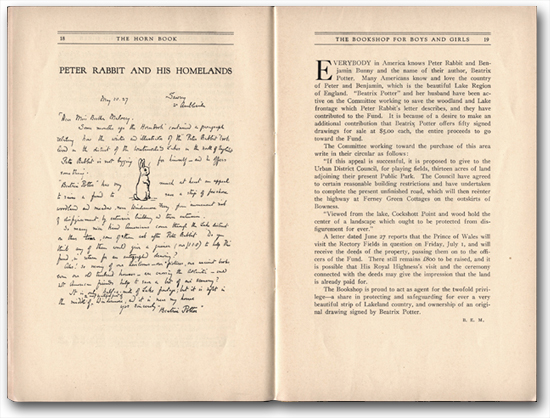

Her first letter under date of May 7, 1927, was concerned with helping to save from commercial exploitation a stretch of beautiful land fronting on Lake Windermere. With it she sent a packet of signed drawings asking if they might be sold through The Bookshop for Boys and Girls and through The Horn Book. This was done, and the entire receipts went toward the desired Fund.

Beatrix Potter's 1927 letter in The Horn Book Magazine

Beatrix Potter's 1927 letter in The Horn Book MagazineRecently, British and American papers have reported Beatrix Potter Heelis's gift to the National Trust of four thousand acres of Lake country in her own county of Westmorland. This bequest includes various farms, woods and cottages and Troutbeck sheep farm at the top of the beautiful Troutbeck Valley — perhaps the entire region covered by The Fairy Caravan. We hope that Hilltop Farm, her own home before her marriage, will be made a memorial to her. Hilltop Farm is the scene, as many will remember, of The Tale of Tom Kitten, The Roly Poly Pudding, Jemima Puddleduck, and Pigling Bland.

It was the earnings from her books, along with a legacy from an aunt, which made possible the purchase of a home in Sawrey, near Ambleside. This farm gradually grew into a large sheep farm and Beatrix Potter herself became an authority on Herdwick sheep. In a letter of November 20, 1942, Mrs. Heelis wrote that Mr. Hudson, the Minister of Agriculture, had telephoned one day, asking her to meet him on Kirkstone Pass for a brief talk on hill farming, as he motored from Scotland to Lancashire. They met as planned; she found him very" cheerful and jolly," and they had a pleasant conversation, but as he looked down into the valley with its bird's-eye view of Troutbeck Park farm, a very thick mist covered everything and Mrs. Heelis's sheep and cattle could not be seen. In the same letter she said: "It is very hard work but I am still managing two sheep farms and the small home farm; and a tractor outfit. I cannot work with my own hands now, like last war; but I'll do my bit till I drop — and enjoy it!"

Last summer I had written of my interest in certain well-written pamphlets published in the British Isles, telling of sheepraising and wool conditions in various parts of the British Commonwealth, and lent to me by a Finnish tailor in our village — a man who worked, when young, in Moscow on uniforms for the Czar's officers. In reply came the following in a letter dated August 18, 1943.

Curious about wool, though perhaps too technical to go into the question. Briefly our Herdwick sheep with their hard water-proof jackets are the only sort that can thrive on the high fells; but the demand for their wool almost ceased when linoleum came in and carpets went out of fashion. At present the price is fixed by Government — 15 1/2 pence instead of 5 to 8 pence, and there is also a subsidy to help hill sheep; so hill sheep farms are paying reasonably well; but we farmers are apprehensive of what will happen after the war. The rate of wages goes up; no one grudges the shepherd his high wages, but if wool drops and the subsidy ends, it's doubtful if Herdwick sheep farms can survive another slump, unless a fresh market can be found for the harsh, hardwearing wool. Government is buying it all; reported to be for khaki and a rumor that the cloth is going to Russia. I wish very much it may be true. Lasting! Your tailor, Mr. Aho, would find it bad for his trade because Herdwick cloth never wears out!

I am in the chair at Herdwick Breeders' Association meetings. You would laugh to see me, amongst the other old farmers, usually in a tavern (!) after a sheep fair.

There had always been occasional brief, but interesting, references in her letters to old furniture. Indeed, one cannot study the drawings and water-colors in her books without realizing her love for fine old furniture and china. It was not until 1934, when I had sent her a catalogue of colonial reproductions in maple made in my husband's factory, that her letters began to reveal her genuine knowledge of antique furniture and period houses. I have taken pains now not to repeat letters quoted in my paper — "Beatrix Potter and Her Nursery Classics" — in The Horn Book for May, 1941, but to enlarge the picture of Mrs. Heelis's interest and activity in this direction.

December 13, 1934

The local furniture in this region was oak; rather out of fashion in the salesrooms now 1'ut I collect any genuine pieces I can get hold of to put back in the farm houses. The court cupboards with carved fronts are the most interesting as they are usually dated. It is a great shame to take them out of the old farm houses for they really don't look well in a modern room. There are a good many cottages belonging t~ the National Trust which will be preserved safely. The oldest I know is 1639.

I am "written out" for story books, and my eyes are tired for painting; but I can still take great and useful pleasure in old oak — and drains — and old roofs — and damp walls — oh, the repairs! And the difficulty of reconciling ancient relics and modern sanitation! An old dame in one of the Trust's cottages wants new window frames .because only two little panes open. A date, March, 1826, is scratched on an old pane.

There was more that was interesting about furniture, architecture and old cottages in a letter of December 18, 1936.

The massive, square furniture has always appeared to me to be a branch of cubism, and the cubic rage in architecture was surely started about the time or soon after the finding of Tutankhamen's tomb — a sort of quasi-Egyptian style. Very fine in the East, and probably tolerable on the English south coast with hot sunshine and rolling chalk downs for background instead of the desert. But most absurdly unsuited to its surroundings when plumped down amongst the English fields and lanes, and especially amongst the Lakes mountains.

There is an outsize large cubist house near Wastwater Lake which looks a1together out of scale, and too exotic, with flat roof, vast curved walls and bare terrace. Advanced, up-to-date, people say we should get used to them; but I do not think flat roofs can be suitable for carrying a weight of snow.

Anyhow the District Council has refused to pass plans for a similar house near Lakeside, Windermere. It is sad how many pretty old cottages are being condemned; slum clearance is necessary in towns, but old fashioned cottages should be re-conditioned in country districts instead of being scrapped. The Council houses which take their place are not solidly built, and yet the rents are beyond what workmen can afford comfortably. It is foolish to have the same regulation for country dwellings and for town back streets. And even in towns — I do love Kendal — fine old houses are piled up along narrow yards, with oak floors and stairs. fortunately most of them are used for office and warehouses; but too much is being pulled down in this craze for rebuilding.

In answer to certain questions I had asked about the pictures in The Tale of Little Pig Robinson, Mrs. Heelis replied on November 24, 1941:

"Stymouth" was Sidmouth on the ouch coast of Devonshire. Other pictures were sketched at Lyme Regis; the steep street looking down hill into the sea; and some of the thatched cottages were near Lyme. The steep village near Lyncon is called Clovelly; I have never seen it, though I know parts of the North Devon coast. Ilfracombe gave me the idea of the long flight of steps down to the harbour. Sidmouth harbour and Teignmouth harbour are not much below the level of the towns. The shipping — including a pig aboard ship — was sketched at Teignmouth, South Devon. The rail wooden shed for drying nets is (or was?) a feature of Hastings, Sussex. So the illustrations are a comprehensive sample of our much battered coast.

In The Horn Book for May, 1929, there appeared, in full, the most important letter we ever received from Beatrix Potter. We had asked her about the roots out of which her work had sprung. Since there are few copies left of that issue of the magazine, and many of our readers today have not seen it, we now reprint parts of it. It seems to explain — so far as genius can ever be explained — how that enchanting blend of the real and the fairy came to be.

The question of "roots" interests me! I am a believer in "breed"; I hold that a strongly marked personality can influence descendants for generations. In the same way that we farmer know chat certain sires — bulls, stallions, rams — have been "prepotent" in forming breeds of shorthorns, thoroughbred , and the numerous varieties of sheep.

I am descended from generations of Lancashire yeomen and weavers; obstinate, hard-headed, matter-of-fact folk. (There you find the downright matter-of-factness which imports an air of reality.) As far back as I can go, they were Puritans Nonjurors, Nonconformists, Dissenters. Your Mayflower ancestors sailed to America; mine at the same date were sticking it out at home; probably rather enjoying persecution.

The most remarkable old "character" amongst my ancestors — old Abraham Crompton, who sprang from mid-Lancashire, bought land for pleasure in the Lake District, and his descendants seem to have drifted back at intervals ever since — though none of us own any of the land that belonged to old Abraham.

However, it was not the Lake District at all that inspired me to write children's books. I hope this shocking statement will not distress you kind Americans, who see Peter Rabbits under every Westmorland bush. I am inclined to put it down to three things, mainly: (1) The aforesaid matter-of-fact ancestry; (2) The accidental circumstance of having spent a good deal of my childhood in the Highlands of Scotland, with a Highland nurse girl and a firm belief in witches, fairies and the creed of the terrible John Calvin (the creed rubbed off, but the fairies remained); (3) A peculiarly precocious and tenacious memory. I have been laughed at for what I say I can remember; but it is admitted that I can remember quite plainly from one and two years old; not only facts, like learning to walk, but places and sentiments — the way things impressed a very young child.

I learned to read on the Waverley novels; I had had a horrid large print primer and a stodgy fat book — I think it was called a History of the Robin Family, by Mrs. Trimmer. I know I hated it. Then I was let loose on Rob Roy, and spelled through a few pages painfully; then I tried Ivanhoe — and The Talisman; — then I tried Rob Roy again; all at once I began to READ (missing the long words, of course), and those great books keep their freshness and charm still. I had very few books — Miss Edgeworth and Scott's novels I read over and over…

In those early days I composed (or endeavoured to compose) hymns imitated from Isaac Watts, and sentimental ballad descriptions of Scottish scenery, which might have been pretty, only I could never make them scan. Then for a long time I gave up trying to write, because I could not do it.

About 1893 I was interested in a little invalid child, the eldest child of a friend; he had a long illness. I used to write letters with pen and ink scribbles, and one of the letters was Peter Rabbit. Noel has got them yet. He grew up and became a hard-working clergyman in a London poor parish.

After a time there began to be a vogue for small books, and I thought "Peter" might do as well as some that were being published. But I did not find any publisher who agreed with me. The manuscript — nearly word for word the same, but with only outline illustrations — was returned with or without thanks by at least six firms.

Then I drew my savings out of the pest office savings bank, and got an edition of 450 copies printed. I think the engraving and printing cost me about £11. It caused a good deal of amusement amongst my relations and friends. I made about £12 or £14 by selling copies to obliging aunts. I showed this privately printed black and white book to Messrs. F. Warne & Co., and the following year, 1901, they brought out the first coloured edition.

The coloured drawings for this were done in a garden near Keswick, Cumberland, and several others were painted in the same part of the· Lake District. Squirrel Nutkin sailed on Derwentwater; Mrs. Tiggywinkle lived in the Vale of Newlands near Keswick. Later books, such as Jemima Puddleduck, Ginger and Pickles, The Pie and the Patty Pan, etc., were done at Sawrey in this southern end of the Lake District. The books relating to Torn Kitten and Samuel Whiskers describe the interior of my old farm house where children are comically impressed by seeing the real chimney and cupboards.

I think I write carefully because I enjoy my writing, and enjoy taking pains over it. I have always disliked writing to order; I write to please myself.

…My usual way of writing is to scribble, and cut out, and write it again and again. The shorter and plainer the better. And read the Bible (unrevised version and Old Testament) if I feel my style wants chastening. There are many dialect words of the Bible and Shakespeare — and also the forcible direct language — still in use in the rural parts of Lancashire.

"Wag-by-Wall," the story which appears in print for the first time in this issue of Horn Book, was originally intended to be a part of The Fairy Caravan. There it was a story told by Jenny Ferret to the Caravaners on a stormy night when they sheltered in an old barn called “High Buildings," far up in the Troutbeck Valley. It had been our first plan to publish the story in The Horn Book for November-December, 1943. We had asked if Sally Benson might sit reading the letter from America on Christmas Eve when the owl and the gold pieces come down the chimney. Then later we wanted to save the story for this, our anniversary issue.

In that last letter, dated November 5, 1943, Beatrix Potter wrote:

I cordially agree with the delay until May for printing the story in The Horn Book. It leaves time to see proofs, and I would like to make it as nearly word-perfect as I know how, for the credit of your 20th anniversary. The winter's snows will be over by then. Would you desire to drop "Christmas Eve"? I am inclined to leave it in, with perhaps an added sentiment about the return of spring. (How the sad world longs for it!) I liked your suggestion of Christmas Eve because I like to think some of your storytellers may read the story turn about with the old Tailor of Gloucester, at Christmas gatherings in the children's libraries.

What a pity Beatrix Potter could not have had a chance to read of the excellence of her prose in the three columns of "Menander's Mirror" section in the London Times Literary Supplement for January 8, 1944, in Margaret Lane's fine critical piece of the same date in the New Statesman and Nation and the New York Herald Tribune's rare editorial of January 6. On June 18, 1942, she wrote she had been sorting over old letters to consign to the pulp heap. She had been freshly amazed at the quantity received from America. She did not receive nearly so many English letters. "But never does anyone outside your perfidiously complimentary nation write to tell me that I write good prose."

"Menander's Mirror," in concluding, says the rule Beatrix Potter obeyed is "the old one: a beginning, a middle, an end; an illusion sufficient to maintain suspense of plot; a good humour warm enough to yield the pleasures of good company." He quotes the opening lines of The Tale of Peter Rabbit as showing her gift of attack and after quoting it writes: "Goldsmith could not have opened more plainly or Stevenson have wasted less time. Lovely as are the illustrations, their virtue is that they fulfill the text." All agree that Beatrix Potter "made and peopled a world, and brought it perfectly to life — which is what Dickens and Trollope did, on a different scale."

From the May 1944 issue of The Horn Book Magazine

RELATED

RECOMMENDED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy: