What Makes a Good Picture Book About Loss?

The three-hankie middle grade novel is a literary tradition as old as time (or at least as old as Charlotte’s Web).

Those of us concerned with young people and their reading recognize the appeal and value of books such as these. While tearjerkers may not enjoy the same market share as daft diaries and action-packed adventure series, they do have a devoted following. And books that speak to sadness — that acknowledge its very existence — help establish loss and grief as part of the human condition and offer opportunities to practice their processing.

Sad books are more difficult to find in the picture book canon, amidst the boisterous alphabets and sunny barnyards and irreverent pigeons. This is not to say that picture books are a homogeneous lot, for we know that they are not. Nor is it to say that they are devoid of darkness. The prevalence of fairy-tale picture books, for example — and the fearsome goblins, trolls, and witches therein — demonstrates that children have an appetite for dread. We do not, however, see a micro-genre of grief- and loss-themed picture books with runaway appeal.

A small selection of books do exist to help children through the grief associated with the death of a loved one, and many of these books display the hallmarks of exemplary picture-book making. Tomie dePaola’s Nana Upstairs & Nana Downstairs tells the story of dePaola’s own childhood relationships with his grandmother and great-grandmother, whom he would visit every Sunday. The author fills the text and illustrations with fond, personal, sometimes humorous details (e.g., the family tied his great-grandmother into her Morris chair to prevent her falling out), giving the story a tender immediacy that is perfectly suited to the nostalgic subject matter and establishing family love as life’s central theme — and death as one of its necessary components.

A small selection of books do exist to help children through the grief associated with the death of a loved one, and many of these books display the hallmarks of exemplary picture-book making. Tomie dePaola’s Nana Upstairs & Nana Downstairs tells the story of dePaola’s own childhood relationships with his grandmother and great-grandmother, whom he would visit every Sunday. The author fills the text and illustrations with fond, personal, sometimes humorous details (e.g., the family tied his great-grandmother into her Morris chair to prevent her falling out), giving the story a tender immediacy that is perfectly suited to the nostalgic subject matter and establishing family love as life’s central theme — and death as one of its necessary components.In contrast to the trademark sentiment of dePaola’s work, Judith Viorst’s The Tenth Good Thing About Barney, illustrated by Erik Blegvad, employs direct prose and spare etchings to recount the death of a boy’s cat and the small funeral the family undertakes. Viorst focuses on the power of memory as a path through grieving, and the book’s cool crosshatched imagery sets a mood of quiet contemplation. The books are markedly different, yet each explores its subject in a deeply personal yet universally relatable way, and it is this distinction that marks the volumes as fine picture books.

There are some contemporary exemplars as well. Rebecca Cobb’s Missing Mommy pairs a young child’s concerns about the loss of a parent (“I am worried that she left because I was naughty sometimes”) with scribbly, childlike drawings. The naive style of the imagery is well matched to the innocence of the perspective, adding a literary harmony to the exposition of the psychological truths about bereavement.

There are some contemporary exemplars as well. Rebecca Cobb’s Missing Mommy pairs a young child’s concerns about the loss of a parent (“I am worried that she left because I was naughty sometimes”) with scribbly, childlike drawings. The naive style of the imagery is well matched to the innocence of the perspective, adding a literary harmony to the exposition of the psychological truths about bereavement.Saying Goodbye to Lulu by Corinne Demas, illustrated by Ard Hoyt, takes an unflinching look at a family dog’s final days, as a little girl struggles to comfort Lulu and reconcile herself to the dog’s passing. Hoyt’s flush, animate drawings hum with life, giving Demas’s clear-eyed telling a gentle heartbeat to provide the utmost, and most excruciating, potency.

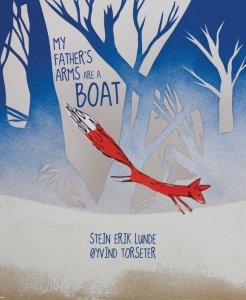

My Father’s Arms Are a Boat by Stein Erik Lunde, illustrated by Øyvind Torseter, depicts a single, quiet episode in a family’s grieving. A boy lies sleepless, listening to the silence. He goes to his father, who wraps him in a sheepskin coat and takes him out into a snowy night of gray and black where they talk of foxes and bread and stars and wishes. Only passing reference is made to the death of the boy’s mother. Instead, the lyrical language and still, dioramic illustrations observe the evening’s simple spectacle, with all the intimacy of warm detail. The pair returns home and, as the fire casts a brilliant orange glow, the father’s promise that everything will be all right is echoed by the rising of another sun. With layers of meaning and metaphor, this book offers profound insights into nature’s immutable, cyclical dance, messages that extend well beyond the specificity of the circumstance.

My Father’s Arms Are a Boat by Stein Erik Lunde, illustrated by Øyvind Torseter, depicts a single, quiet episode in a family’s grieving. A boy lies sleepless, listening to the silence. He goes to his father, who wraps him in a sheepskin coat and takes him out into a snowy night of gray and black where they talk of foxes and bread and stars and wishes. Only passing reference is made to the death of the boy’s mother. Instead, the lyrical language and still, dioramic illustrations observe the evening’s simple spectacle, with all the intimacy of warm detail. The pair returns home and, as the fire casts a brilliant orange glow, the father’s promise that everything will be all right is echoed by the rising of another sun. With layers of meaning and metaphor, this book offers profound insights into nature’s immutable, cyclical dance, messages that extend well beyond the specificity of the circumstance.And there is the rub. Picture books such as these have things to say to children, about life and family and love and loss. And the best of them say these things in artful and compelling ways, as pieces of engaging and gratifying literature. Yet they are relegated to bibliotherapy. We look to them when events in a child’s life precipitate an immediate need. And, generally, we look to them only then. In contrast, the middle-grade classic Where the Red Fern Grows by Wilson Rawls, for example, has enchanted generations of readers with its heart-rending evocation of the love between a boy and his dogs, made all the more visceral by the dogs’ deaths. I imagine that most of the novel’s readers have found and loved it independent of a corresponding loss in their own lives. Saying Goodbye to Lulu communicates a similar kind of love and loss in just the same way, with the same moving narrative power. But is it reaching as broad an audience of picture book readers, those small children whose dogs haven’t just died?

One of our primary vehicles for connecting young people with picture books is shared reading. Storytimes in schools and public libraries are meant to delight children with the joys of books and reading, leveraging the most engaging literature at our disposal. Our first choice of book to share with poor, unsuspecting young ones wouldn’t be a dead-dog story, would it? Well, why not? If indeed the purpose of storytime is to introduce kids to the breadth and power of books and stories, wouldn’t it make sense to include as wide a variety of good literature as possible? Admittedly, books of bubbly humor and silliness intoxicate a preschool audience, eliciting the kind of raucous laughter so gratifying to the reader-aloud. But if we limit ourselves to that kind of material, are we suggesting to children and their families that those are the best, or only, books to read aloud? Or, worse, are we sending a message that exuberant happiness is the only emotion that picture books engage, or the only emotion to legitimately consider or experience in public?

Before the Little Bear series that would make them famous, Martin Waddell and Barbara Firth collaborated on We Love Them about a brother and sister who live on a farm. The boy relates the story of their dog, Ben, who finds a baby rabbit, whom the siblings name Zoe, in the snow. Ben and Zoe enjoy a long life together, until one day Ben dies. Not long after, the siblings find a puppy in the hay. And the cycle continues. Waddell’s open verse and Firth’s soft, sun-filled watercolors make for a lovely book perfectly suited for reading aloud. I have shared the book with groups of children many times, with great success. There is often a gasp when Ben dies, but only because the kids, and their grown-ups, are riveted. It is almost as if kids are surprised at the events in the story and the adults are shocked that I would read them aloud. Invariably, though, the children respond to the whole book, understanding the sadness as one part of the story’s longer arc, and the adults relax, a few of them having had an epiphany of their own.

Before the Little Bear series that would make them famous, Martin Waddell and Barbara Firth collaborated on We Love Them about a brother and sister who live on a farm. The boy relates the story of their dog, Ben, who finds a baby rabbit, whom the siblings name Zoe, in the snow. Ben and Zoe enjoy a long life together, until one day Ben dies. Not long after, the siblings find a puppy in the hay. And the cycle continues. Waddell’s open verse and Firth’s soft, sun-filled watercolors make for a lovely book perfectly suited for reading aloud. I have shared the book with groups of children many times, with great success. There is often a gasp when Ben dies, but only because the kids, and their grown-ups, are riveted. It is almost as if kids are surprised at the events in the story and the adults are shocked that I would read them aloud. Invariably, though, the children respond to the whole book, understanding the sadness as one part of the story’s longer arc, and the adults relax, a few of them having had an epiphany of their own. A recent trend in publishing complements these straightforward stories with more abstracted explorations of loss and death. In the picture book Today and Today, G. Brian Karas knits together a sampling of haiku from eighteenth-century Japanese poet Kobayashi Issa, using the poems to adorn a pictorial narrative of one family’s loss of a grandparent. The story begins in spring, with children playing in a field while an older man sits in a chair beneath a cherry tree in bloom. Summer comes and the children play on their own. In fall, the old man sits in his chair, wrapped in a blanket, as the family tends the yard around him. At the advent of winter, the chair stands empty. Snow falls, fol lowed by trips to the hospital, and then the cemetery. And spring returns. The book is extraordinary for many reasons. Structurally the words and pictures switch traditional roles, with the images carrying the arc of the story and the poems providing tonal embellishment. The tension between the homespun, cartoony nature of Karas’s illustrations and the graceful elegance of the haiku gives the book a quiet, vital energy that fills the pages with life. Because the text makes no reference at all to the story’s events, the narrative is especially permeable, allowing readers and listeners to insert their own imaginings.

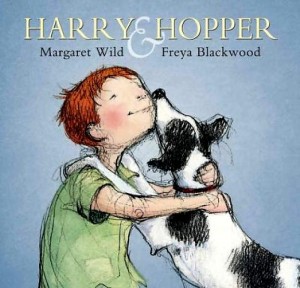

A recent trend in publishing complements these straightforward stories with more abstracted explorations of loss and death. In the picture book Today and Today, G. Brian Karas knits together a sampling of haiku from eighteenth-century Japanese poet Kobayashi Issa, using the poems to adorn a pictorial narrative of one family’s loss of a grandparent. The story begins in spring, with children playing in a field while an older man sits in a chair beneath a cherry tree in bloom. Summer comes and the children play on their own. In fall, the old man sits in his chair, wrapped in a blanket, as the family tends the yard around him. At the advent of winter, the chair stands empty. Snow falls, fol lowed by trips to the hospital, and then the cemetery. And spring returns. The book is extraordinary for many reasons. Structurally the words and pictures switch traditional roles, with the images carrying the arc of the story and the poems providing tonal embellishment. The tension between the homespun, cartoony nature of Karas’s illustrations and the graceful elegance of the haiku gives the book a quiet, vital energy that fills the pages with life. Because the text makes no reference at all to the story’s events, the narrative is especially permeable, allowing readers and listeners to insert their own imaginings. Harry & Hopper by Margaret Wild, illustrated by Freya Blackwood, adds a touch of magical realism to the story of a boy, Harry, whose dog, Hopper, dies in an accident. For several nights thereafter, Hopper returns to Harry’s window and the two play together, just like old times. But each night Hopper is a bit less substantial (communicated brilliantly in text and illustration), and in time Harry is ready to let go. Eric Rohmann takes a similar conceit in a different direction with Bone Dog. On Halloween night a boy named Gus is beset by menacing skeletons. His recently deceased dog, Ella, returns (at least her bones do) to help him; after all, to a dog, even a ghostly one, an onslaught of skeletons is akin to a smorgasbord. At first the story’s injection of playful humor feels a bit off, but with it, Rohmann demonstrates that responses to grief are compound and sometimes unexpected. He shows us, too, that thirty-two pages are more than enough to explore this complexity.

Harry & Hopper by Margaret Wild, illustrated by Freya Blackwood, adds a touch of magical realism to the story of a boy, Harry, whose dog, Hopper, dies in an accident. For several nights thereafter, Hopper returns to Harry’s window and the two play together, just like old times. But each night Hopper is a bit less substantial (communicated brilliantly in text and illustration), and in time Harry is ready to let go. Eric Rohmann takes a similar conceit in a different direction with Bone Dog. On Halloween night a boy named Gus is beset by menacing skeletons. His recently deceased dog, Ella, returns (at least her bones do) to help him; after all, to a dog, even a ghostly one, an onslaught of skeletons is akin to a smorgasbord. At first the story’s injection of playful humor feels a bit off, but with it, Rohmann demonstrates that responses to grief are compound and sometimes unexpected. He shows us, too, that thirty-two pages are more than enough to explore this complexity. Bob Staake’s wordless Bluebird makes something universal of loss, imagining a fantastical situation outside most children’s experience. A boy is bullied, rather mercilessly, and he roams the city streets, friendless. He is adopted by a little blue bird who becomes his trusted companion. The bullies persist, though, and in a particularly brutal attack, the bird is struck by a stick and killed. A rainbow of other birds arrives, and boy and bird are flown to the sky where the little blue bird is released. Staake tackles a remarkable range of accordant emotions — grief, guilt, loneliness, hope — evoking them with fierce clarity. By painting such a sweet picture of the pair’s abundant happiness, he offers a precise definition of just what the loss will mean, palpable to readers whether or not they have experienced such privation themselves. He offers, too, an open statement about the life that continues.

Bob Staake’s wordless Bluebird makes something universal of loss, imagining a fantastical situation outside most children’s experience. A boy is bullied, rather mercilessly, and he roams the city streets, friendless. He is adopted by a little blue bird who becomes his trusted companion. The bullies persist, though, and in a particularly brutal attack, the bird is struck by a stick and killed. A rainbow of other birds arrives, and boy and bird are flown to the sky where the little blue bird is released. Staake tackles a remarkable range of accordant emotions — grief, guilt, loneliness, hope — evoking them with fierce clarity. By painting such a sweet picture of the pair’s abundant happiness, he offers a precise definition of just what the loss will mean, palpable to readers whether or not they have experienced such privation themselves. He offers, too, an open statement about the life that continues.While these expressionistic explorations of loss eschew the more linear directions of their forebears, they are no less suitable for group sharing. In their experimental approaches to storytelling and the poignant drama of their content, they provide a welcome balance to the boisterous hilarity that dominates the read-aloud landscape.

In an effort to spare children discomfort, we fill their environments with primary colors and fun and cuddles, and purge those environments of any references to despair or struggle. We don’t want the kids in our lives to be unhappy, after all. But kids despair and they struggle. And should not books be places for kids to make sense of those emotions? There is a place in the picture-book world for books that acknowledge hurt and sorrow, books that recognize that such emotions exist and tell kids that it’s okay to feel them. We owe it to the children we serve, and the families who love them, to make their literary acquaintance broad and rich. They must understand that stories reflect the whole of their emotional experience, not just the exciting and funny bits. By introducing very young children to books and stories as opportunities to validate and communicate all of our feelings, we give them a powerful gift indeed.

Good Picture Books About Loss

Missing Mommy: A Book About Bereavement (Holt, 2013) by Rebecca Cobb

Saying Goodbye to Lulu (Little, Brown, 2004) by Corinne Demas; illus. by Ard Hoyt

Nana Upstairs & Nana Downstairs (Putnam, 1973 [reissued with new illustrations, 1997]) by Tomie dePaola

Today and Today (Scholastic, 2007) by Kobayashi Issa; illus. by G. Brian Karas

My Father’s Arms Are a Boat (Enchanted Lion, 2013) by Stein Erik Lunde; trans. from the Norwegian by Kari Dickson; illus. by Øyvind Torseter

Bone Dog (Roaring Brook, 2011) by Eric Rohmann

Bluebird (Schwartz & Wade/Random, 2013) by Bob Staake

The Tenth Good Thing About Barney (Atheneum, 1971) by Judith Viorst; illus. by Erik Blegvad

We Love Them (Lothrop, Lee & Shepard, 1990) by Martin Waddell; illus. by Barbara Firth

Harry & Hopper (Feiwel, 2011) by Margaret Wild; illus. by Freya Blackwood

From the September/October 2013 issue of The Horn Book Magazine.

says

says

says

says

says

says

says

says

says

says

says

says

Add Comment :-

RELATED

RECOMMENDED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.