2018 School Spending Survey Report

What Makes a Good Fractured Fairy Tale?

Primary school–age children are ripe for enjoying literary parody, and fractured fairy tales are a great introduction.

It’s that familiarity with the original that makes reading or listening to a parody so satisfying — that feeling of being in on a joke. Your younger, less sophisticated sibling might not get it, but you know how this story is supposed to go, which makes it all the funnier when it goes off in a different direction.

There are probably as many ways to fracture a fairy tale as there are to fracture your leg. Some make for great stories, and some are just, well, not all that interesting, like those that rely merely on a change of setting, or simply substitute one type of animal for another, or even throw in some vampires or ninjas. The good ones are those that really twist your perspective on the story, showing you its other possibilities.

It probably goes without saying that the ultimate fractured fairy-tale picture book is The Stinky Cheese Man and Other Fairly Stupid Tales, a product of the hilariously strange imaginations of Jon Scieszka and Lane Smith. Really, all you have to do is say the title to a group of kids and they’ll start cracking up, either because they’ve already read it, or because the words stinky cheese (not to mention stupid) are so extremely funny, or both. (Side note: a former administrator at the school where I work once made a guest appearance in the library to read selections from the book, and he actually brought in a hunk of pungent cheese for the kids to smell. It wasn’t strictly necessary to their enjoyment of the stories, but it was a nice touch.)

It probably goes without saying that the ultimate fractured fairy-tale picture book is The Stinky Cheese Man and Other Fairly Stupid Tales, a product of the hilariously strange imaginations of Jon Scieszka and Lane Smith. Really, all you have to do is say the title to a group of kids and they’ll start cracking up, either because they’ve already read it, or because the words stinky cheese (not to mention stupid) are so extremely funny, or both. (Side note: a former administrator at the school where I work once made a guest appearance in the library to read selections from the book, and he actually brought in a hunk of pungent cheese for the kids to smell. It wasn’t strictly necessary to their enjoyment of the stories, but it was a nice touch.)The tales are delightfully irreverent. The ugly duckling, despite his confidence that he will someday grow up to be a beautiful swan, just grows up to be an ugly duck; the princess kisses the frog for nothing; and Cinderella is too dense to recognize a solution to her problem when it’s standing right there shouting at her. But it’s not just the stories that are parodies, it’s the whole package, from title page to dedication to Surgeon General’s Warning. The Little Red Hen takes possession of the front matter to browbeat us (“But who will help me tell my story? Who will help me draw a picture of the wheat? Who will help me spell ‘the wheat’?”), and the table of contents falls down and squashes everyone, despite all of Chicken Licken’s warnings. We can’t trust anyone or anything in this world, including Scieszka and Smith’s jacket-flap author and illustrator bios.

In the nearly quarter-century since this book was published, metafiction has come to seem almost obligatory, and it often feels more like a clever diversion for adult readers than anything else. This one, however, was aimed squarely at kids at the age when they are learning the structure and conventions of stories as well as the structure and conventions of books themselves. Scieszka and Smith never talk down to their audience — the humor and artwork are sophisticated and reward repeated readings, yet they are rooted in things kids understand and find funny. Like stinky cheese.

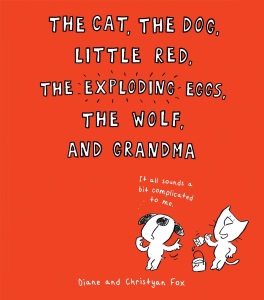

With The Cat, the Dog, Little Red, the Exploding Eggs, the Wolf, and Grandma, Diane and Christyan Fox take the “Little Red Riding Hood” story completely apart and in the process remind us how truly strange these old stories are. The familiar elements of the setting (cozy cottage, dark forest) are nowhere to be seen. Instead, on pages with abundant white space, in drawings that are mostly black-and-white with spots of color, we have a cartoon cat and dog alternately reading, arguing about, and acting out “Little Red Riding Hood.” The dog, unfamiliar with the story, keeps trying to turn it into something else entirely. A little girl who wears a red cape with a hood? She must be a superhero! Does she zap bad guys with her kindness ray? When the cat, with growing exasperation, at last convinces him it’s not that kind of story, the dog begins to question the tale’s logic. Why doesn’t the wolf just eat Little Red when he first meets her? Does he like dressing up in girls’ clothes? And why isn’t it glaringly obvious to Little Red that that’s a wolf lying in the bed, and not her grandma? By the time the dog learns the story’s violent end and asks, “Are you absolutely sure this is a children’s book?” we are scratching our own heads in amused bewilderment.

With The Cat, the Dog, Little Red, the Exploding Eggs, the Wolf, and Grandma, Diane and Christyan Fox take the “Little Red Riding Hood” story completely apart and in the process remind us how truly strange these old stories are. The familiar elements of the setting (cozy cottage, dark forest) are nowhere to be seen. Instead, on pages with abundant white space, in drawings that are mostly black-and-white with spots of color, we have a cartoon cat and dog alternately reading, arguing about, and acting out “Little Red Riding Hood.” The dog, unfamiliar with the story, keeps trying to turn it into something else entirely. A little girl who wears a red cape with a hood? She must be a superhero! Does she zap bad guys with her kindness ray? When the cat, with growing exasperation, at last convinces him it’s not that kind of story, the dog begins to question the tale’s logic. Why doesn’t the wolf just eat Little Red when he first meets her? Does he like dressing up in girls’ clothes? And why isn’t it glaringly obvious to Little Red that that’s a wolf lying in the bed, and not her grandma? By the time the dog learns the story’s violent end and asks, “Are you absolutely sure this is a children’s book?” we are scratching our own heads in amused bewilderment. One of the most profound things a parody can do is to take down the powerful, making the villain ridiculous and inspiring our derision or, in some cases, our sympathy. Eugene Trivizas reverses the roles of villain and victim in The Three Little Wolves and the Big Bad Pig, illustrated by Helen Oxenbury. How could we ever have thought that these fluffy little creatures were frightening, with their china teapot, their croquet games, and their wide, startled eyes when that nasty pig comes after them? When their last refuge, an iron and barbed-wire bunker, is dynamited to bits, their solution is a house made of flowers. Even the big bad pig can’t resist its fragile beauty. And as he breathes in, preparing to huff and puff, he is instead filled with the sweet scent and becomes a new

pig altogether, gentle and remorseful. The tables, already turned once, are turned inside out.

One of the most profound things a parody can do is to take down the powerful, making the villain ridiculous and inspiring our derision or, in some cases, our sympathy. Eugene Trivizas reverses the roles of villain and victim in The Three Little Wolves and the Big Bad Pig, illustrated by Helen Oxenbury. How could we ever have thought that these fluffy little creatures were frightening, with their china teapot, their croquet games, and their wide, startled eyes when that nasty pig comes after them? When their last refuge, an iron and barbed-wire bunker, is dynamited to bits, their solution is a house made of flowers. Even the big bad pig can’t resist its fragile beauty. And as he breathes in, preparing to huff and puff, he is instead filled with the sweet scent and becomes a new

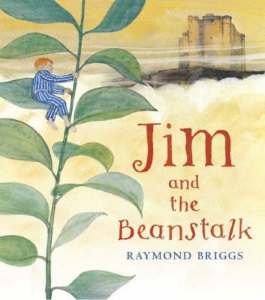

pig altogether, gentle and remorseful. The tables, already turned once, are turned inside out. Raymond Briggs creates a hilariously feeble villain in his classic Jim and the Beanstalk. This giant is enormous, but he’s also awfully old. Bald and toothless, he can’t even enjoy his poetry books anymore because the print is too small for him to read. When Jim, having climbed the beanstalk, arrives at his door, the giant says, rather pathetically, “Come on in, boy. You’re safe.” Even in the end, as the spruced-up giant (with wig, glasses, and false teeth provided by Jim) delightedly dances around the room and warns Jim that he’d better leave immediately or be eaten, we get the feeling that Jim complies not because he’s scared but rather in the spirit of humoring his no-longer-so-terrifying neighbor.

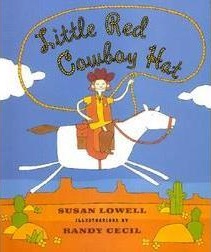

Raymond Briggs creates a hilariously feeble villain in his classic Jim and the Beanstalk. This giant is enormous, but he’s also awfully old. Bald and toothless, he can’t even enjoy his poetry books anymore because the print is too small for him to read. When Jim, having climbed the beanstalk, arrives at his door, the giant says, rather pathetically, “Come on in, boy. You’re safe.” Even in the end, as the spruced-up giant (with wig, glasses, and false teeth provided by Jim) delightedly dances around the room and warns Jim that he’d better leave immediately or be eaten, we get the feeling that Jim complies not because he’s scared but rather in the spirit of humoring his no-longer-so-terrifying neighbor. In other stories, the bully remains a bully, and it’s the victim/heroine who reacts unexpectedly, as in, for example, Susan Lowell’s Little Red Cowboy Hat, illustrated by Randy Cecil. I’m not talking about Little Red here, though she is certainly spunky in her cowboy hat, doing tricks on her pony. No, I’m talking about Grandma. Far from being a sweet, elderly lady quivering in her nightgown and waiting for that brave woodcutter to show up, she’s a tough old dame in cowboy boots, her mouth set in a grim line, who takes off after the wolf, firing her shotgun and hurling colorful epithets. It might not be groundbreaking as a parody, but it’s really funny. “That yellow-bellied, snake-blooded, skunk-eyed rancid son of a parallelogram!” she tells her granddaughter with satisfaction, “This time he picked the wrong grandma.” You might have missed it (and it’s understandably not depicted in the illustrations), but I’m pretty sure she shot that wolf dead. SPLAT.

In other stories, the bully remains a bully, and it’s the victim/heroine who reacts unexpectedly, as in, for example, Susan Lowell’s Little Red Cowboy Hat, illustrated by Randy Cecil. I’m not talking about Little Red here, though she is certainly spunky in her cowboy hat, doing tricks on her pony. No, I’m talking about Grandma. Far from being a sweet, elderly lady quivering in her nightgown and waiting for that brave woodcutter to show up, she’s a tough old dame in cowboy boots, her mouth set in a grim line, who takes off after the wolf, firing her shotgun and hurling colorful epithets. It might not be groundbreaking as a parody, but it’s really funny. “That yellow-bellied, snake-blooded, skunk-eyed rancid son of a parallelogram!” she tells her granddaughter with satisfaction, “This time he picked the wrong grandma.” You might have missed it (and it’s understandably not depicted in the illustrations), but I’m pretty sure she shot that wolf dead. SPLAT. Another spry (both mentally and physically) grandma — albeit more of a pacifist than the former example — appears in Susan Middleton Elya’s Little Roja Riding Hood, a parody that incorporates Spanish words and phrases into the energetic rhyming text. In Susan Guevara’s illustrations, Abuela, wearing peace-sign PJs, is in bed with her laptop when the wolf bursts in. She and Little Roja (who drives an ATV and can take care of herself, thank you very much) make a more-than-capable team and handily dispatch the lobo — “no problema!”

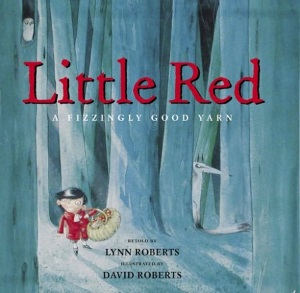

Another spry (both mentally and physically) grandma — albeit more of a pacifist than the former example — appears in Susan Middleton Elya’s Little Roja Riding Hood, a parody that incorporates Spanish words and phrases into the energetic rhyming text. In Susan Guevara’s illustrations, Abuela, wearing peace-sign PJs, is in bed with her laptop when the wolf bursts in. She and Little Roja (who drives an ATV and can take care of herself, thank you very much) make a more-than-capable team and handily dispatch the lobo — “no problema!” In Little Red: A Fizzingly Good Yarn, Lynn Roberts opens up the possibilities of this story with a gender switch, a different setting, and the sheer inventiveness of her solution to the wolf problem. This Little Red is a boy, comically innocent and helpless-looking with his round googly eyes, and the setting is colonial America, complete with roadside inns and buckled shoes. In David Roberts’s illustrations, the inn and its guests, the forest and the lurking wolf all have a spindly, shadowy, shifty-eyed menace, but we are still unprepared for the wonderfully shocking sight of Grandma in the process of being swallowed by the wolf. Clad in Little Red’s too-small jacket, the wolf is in the air, on a diagonal trajectory flying downward across the page. Grandma’s wig, cane, and lorgnette go flying from her hands, and her dainty feet have left their shoes as her head and shoulders disappear into the wolf’s enormous jaws. Fortunately, Little Red has brought a jug of Grandma’s favorite ginger ale with him, and once he convinces the wolf to drink it down, the process is reversed, with a startled-looking Grandma shooting out of the wolf’s mouth as if from a cannon from the force of his enormous, ginger ale–induced belch. I don’t have to tell you that it brings down the house.

In Little Red: A Fizzingly Good Yarn, Lynn Roberts opens up the possibilities of this story with a gender switch, a different setting, and the sheer inventiveness of her solution to the wolf problem. This Little Red is a boy, comically innocent and helpless-looking with his round googly eyes, and the setting is colonial America, complete with roadside inns and buckled shoes. In David Roberts’s illustrations, the inn and its guests, the forest and the lurking wolf all have a spindly, shadowy, shifty-eyed menace, but we are still unprepared for the wonderfully shocking sight of Grandma in the process of being swallowed by the wolf. Clad in Little Red’s too-small jacket, the wolf is in the air, on a diagonal trajectory flying downward across the page. Grandma’s wig, cane, and lorgnette go flying from her hands, and her dainty feet have left their shoes as her head and shoulders disappear into the wolf’s enormous jaws. Fortunately, Little Red has brought a jug of Grandma’s favorite ginger ale with him, and once he convinces the wolf to drink it down, the process is reversed, with a startled-looking Grandma shooting out of the wolf’s mouth as if from a cannon from the force of his enormous, ginger ale–induced belch. I don’t have to tell you that it brings down the house. Like Little Red Riding Hood, Goldilocks can be exasperating in her innocence and haplessness, making her the perfect victim for Mo Willems (not to mention a family of dinos) in Goldilocks and the Three Dinosaurs. Willems uses the kind of broad strokes of irony that kids love. The dinosaurs rub their hands together as they hatch their plot, eyes narrowed with evil glee, and Mama Dinosaur booms, “I sure hope no innocent little succulent child happens by our unlocked home while we are…uhhh…someplace else!” It’s great fun watching Goldilocks dopily skipping through the forest and exploring the dinosaurs’ house, actually swimming through bowls of chocolate pudding in her greed, completely missing the obvious danger signs (from a signpost reading “.2 miles to trap” where “trap” has been amended to “very nice house,” to family portraits of dinosaurs on the wall and a doormat that reads “Wipe your talons”). By the time the dinosaurs finally charge into the house, ready to eat her, we almost hope they succeed. She escapes, of course, but at least we have the consolation of seeing her, two pages later, show up at the bears’ house, smiling with her arms outstretched as if for a hug.

Like Little Red Riding Hood, Goldilocks can be exasperating in her innocence and haplessness, making her the perfect victim for Mo Willems (not to mention a family of dinos) in Goldilocks and the Three Dinosaurs. Willems uses the kind of broad strokes of irony that kids love. The dinosaurs rub their hands together as they hatch their plot, eyes narrowed with evil glee, and Mama Dinosaur booms, “I sure hope no innocent little succulent child happens by our unlocked home while we are…uhhh…someplace else!” It’s great fun watching Goldilocks dopily skipping through the forest and exploring the dinosaurs’ house, actually swimming through bowls of chocolate pudding in her greed, completely missing the obvious danger signs (from a signpost reading “.2 miles to trap” where “trap” has been amended to “very nice house,” to family portraits of dinosaurs on the wall and a doormat that reads “Wipe your talons”). By the time the dinosaurs finally charge into the house, ready to eat her, we almost hope they succeed. She escapes, of course, but at least we have the consolation of seeing her, two pages later, show up at the bears’ house, smiling with her arms outstretched as if for a hug.One of the best things about these characters is how game they are. Okay, so things didn’t go as planned; well, what can be done about it? Maybe a house of flowers would work out better in the long run than barbed wire. Maybe that giant really needs something to give his self-esteem a boost. Maybe that jug of ginger ale you’re carrying around could be a useful weapon. As in fractured fairy tales, so it can be in life. When confronted by difficult people (or giants, wolves, or dinosaurs) or scary situations (like, say, being eaten), sometimes you have to fight, sometimes you just have to hope for the best, but sometimes, with humor and imagination, you can look at things a different way and change the story. And the sooner kids discover that, the better.

Good Fractured Fairy Tales

Jim and the Beanstalk (Putnam, 1970) by Raymond Briggs

Little Roja Riding Hood (Putnam, 2014) by Susan Middleton Elya; illus. by Susan Guevara

The Cat, the Dog, Little Red, the Exploding Eggs, the Wolf, and Grandma (Scholastic, 2014) by Diane Fox and Christyan Fox

Little Red Cowboy Hat (Holt, 1997) by Susan Lowell; illus. by Randy Cecil

Little Red: A Fizzingly Good Yarn (Abrams, 2005) by Lynn Roberts; illus. by David Roberts

The Stinky Cheese Man and Other Fairly Stupid Tales (Viking, 1992) by Jon Scieszka; illus. by Lane Smith

The Three Little Wolves and the Big Bad Pig (McElderry, 1993) by Eugene Trivizas; illus. by Helen Oxenbury

Goldilocks and the Three Dinosaurs (Balzer + Bray/HarperCollins, 2012) by Mo Willems

From the May/June 2015 special issue of The Horn Book Magazine: Transformations.

RELATED

RECOMMENDED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!

Dorothy Gale

Hi! I just have a quick question. For our final writing project assignment, the members in my group want to make a fractured fairy tale on the Wizard of Oz, (the teacher only gave us two choices----the wizard of oz OR Cinderella.) We didn't want to do Cinderella because there are already TONS of stories on that, specific, fairytale. But, I'm having trouble thinking of an idea, because it's also supposed to be from the Wizard's perspective. SOoooo I was just wondering, Is it possible to make a fracture fairytale on this?? Would it be tooooo hard? Could it still be possible from the Wizard's perspective? Pls help! - sorry 4 writing this looooooooooooooooooooooooooooooong comment...Posted : Jun 24, 2018 11:51

Frances Spaltro

Love it - you have helped me decide on several birthday gifts. And perhaps I'll explore these tales for my own enjoyment.Posted : May 27, 2015 08:29