2018 School Spending Survey Report

Tribute to an Artist-Wanderer

by Louise Seaman Bechtel

In the late twenties and early thirties, a happy brew was stirring in the children's book field; much of its spice and a good deal of the steam of the cooking came from the number of artists from all over the world who contributed to its bookmaking.

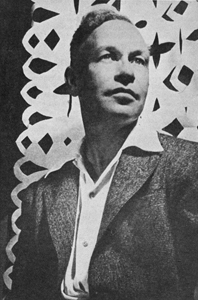

Thomas Handforth at the Seeman School, 1943. (Photo from the October 1950 issue of The Horn Book Magazine)

Thomas Handforth at the Seeman School, 1943. (Photo from the October 1950 issue of The Horn Book Magazine)by Louise Seaman Bechtel

In the late twenties and early thirties, a happy brew was stirring in the children's book field; much of its spice and a good deal of the steam of the cooking came from the number of artists from all over the world who contributed to its bookmaking. The artists as well as the books came here from foreign lands; and our own artists traveled freely, too, to far places. One of the most intelligent of the American wanderers was Thomas Handforth, a young man beset with rather unusual ideas about proving the bases of his style through living in the lands where various styles originated. His wanderings brought us children's books from Morocco, Mexico, China, India. But the bulk of his work was in a great number of etchings, lithographs and paintings which are here described and illustrated. This is a well-deserved tribute, but it is much more than that: through faithful description of the progressive thinking of its subject, it points toward future thinking about the meeting of art cultures of different civilizations.

My first meeting with this young artist was in Morocco through my old friend Elizabeth Coatsworth. She had been there, and on her return had written Toutou in Bondage, a merry story of a stolen dog who finally chose the master who gave him work and fun instead of the mistress who gave him dull comfort. She had suggested an artist known to her through his agent in Hingham, an artist who was most luckily in Morocco. Now my husband and I were on our way to that exciting country. Before we left, some of the pictures arrived, and the book was published in that fall of 1929, the first book of Thomas Handforth.

We met Tom in Rabat, where he had settled down for a while, and made many Arab friends. One young Arab noble had begged him at a party to exchange clothes, so that he could "feel" how it was to wear American trousers. He had gone off for a week with Tom's best suit, leaving this fair-haired, blue-eyed American to go about in flowing Arab robes and headbands. Of course, one in such a costume made a fine guide to Rabat. Only he could have led us to that gay graveyard overlooking the ocean, where parties gather at sunset time. Later we bought Tom’s fine etching which preserves that scene, "Graveyard Chess," a delicate summary of a whole civilization. We wandered, too, in the noisy market place, past the souks, into the fine French colonial museum, and lingered near the doors of the forbidden mosques. We had mint tea with sugared gazelle-horn cakes, looking out toward the famous pirate island.

But Tom's favorite city, and Miss Coatsworth's, and ours too in turn, was Marrakesh. Wilder, more truly Arab than the seaports, a crossroads for distant desert tribes, its primitive beauty has a dramatic setting against the long line of snow-capped Atlas Mountains. As much of all this as possible, especially of Marrakesh, Tom put into the pictures for Toutou. His work for this book is in a style well known in his etchings of this period. He used a delicate, nervous, exotic pattern, but also plenty of emphasis of story details for the action that brings the story to the eye of a child. The book struck a fresh note, both French and Arab in its undertones, sophisticated, gay, decorative, subtle, alive yet also a bit decadent. As a good, thinking artist, Tom could not have lived with that style for too long.

This unusual book was a bit too "special." Morocco could not win many hearts, even when there was a little dog for hero. Marrakesh was waiting for Mr. Churchill to add to its fame by painting there. The book was one to be proud of, but it has been out of print for some years. Today, it looks as fresh and distinguished as it did in 1929. Perhaps it will be the French in Morocco who will give it another lease of life, for it catches all the charm of the old Arab ways as only one who lived there could see them. There is predominating humor, besides loving appreciation. The decorative approach never hides the fundamental good drawing.

Next, from Mexico came his drawings for Susan Smith's Tranquilina's Paradise (Minton, Balch) in 1930; then Mei Li in 1938 and Faraway Meadow (both Doubleday) from India in 1939. The last two had his own stories. In 1944, he illustrated The Dragon and the Eagle by Delia Goetz, happily lending his more humorous memories of his beloved China to a booklet of the Foreign Policy Association. Memories of China again brought charm and authenticity to Margery Evernden's Secret of the Porcelain Fish (Random, 1947). This lovely book and Mei Li alone are still in print.

For, as his Caldecott Medal book, Mei Li, so well proved, it was China that gave him his deepest inspiration. Best known of all his books, most appealing to children, still deservedly alive and popular, Mei Li shows him at his full strength as an artist. On every bold, big page it proves him akin to those great Chinese artists of old. Here he is saying something about that dream of uniting the arts of East and West. Such an inspiration could not have come from the static art of the Arab. Nor would he have found it in China had he not lived there and loved it as a home. How easily he could have gone on, doing other picture-story books in this same adapted Chinese style, bringing us other aspects of China. In fact, from the piles of drawings, prints, photographs, he left, much more is available for books. But war drove him home to America, and he was diverted to painting for a while and to that extraordinary work with mentally retarded boys of which you will read here. One night he brought to dinner at our apartment in New York a huge case of the paintings these boys had done with him. It was a startling, moving experience to see these paintings, and to hear him tell which sorts of mental states produced them. It was a bitter disappointment to him that, after all the time he spent explaining them to art people and to medical men, they had no public showing during his lifetime. That showing was arranged by his friends after his death. But the work has not yet had the impact on both the art and medical worlds that he had hoped for.

Let me end on a gayer note. All of Tom's friends must have shared with me those extraordinary Christmas cards of his. With finical care and obvious gay delight, he would put together odd bits of Oriental papers, gilt laces, pictures, cutting, pasting, redesigning, until each of us had an individual treasure to bring his greetings. I look from one of these shining on my desk, to the wall where has hung for so many years one of his brush drawings of a Chinese mother and child, a portrait strong, simple, dignified, a noble tribute to a Chinese friend.

I wish he could have fulfilled further both these aspects of his bright promise. But he left more in accomplished work — etchings, lithographs, paintings — than many a one who lived much longer. These works will live, as will at least one of his books. So will that special intelligence that made him an artist-wanderer-thinker, and endeared him to Arabs, Mexicans, Chinese, Indians, and to us many lucky Americans who called him friend and miss his presence.

This article by Louise Seaman Bechtel originally appeared in the October 19, 1950 extra issue of The Horn Book Magazine and is part of our Caldecott at 75 celebration. Click here for more archival Horn Book material on Thomas Handforth and Mei Li.

RELATED

RECOMMENDED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!