To Get a Little More of the Picture: Reviewing Picture Books

"It is only in childhood that books have any deep influence on our lives.

"It is only in childhood that books have any deep influence on our lives."

— Graham Greene

"Any book which is at all important should be reread immediately."

— Schopenhauer

The management has suggested that I review picture book reviewing. "Feel free to rant about its sorry state." I also feel wary, as I did when I first began to review children's books in the 1970s. I had written and/or illustrated more than twenty-five books by then, and believed that I knew from both my education (in graphic arts) and my vocation a good deal about the subject. So when I was given the opportunity to voice some of the many opinions I had been storing up, I shivered slightly and jumped in.

Of course I was already aware, from personal experience, just how pleasant it is to be well reviewed, how devastating to be devastated. But would that make me a responsible reviewer? Could I be objective and generous enough with other people's work? Fortunately, I quickly realized that it is always a major pleasure and triumph to discover good new work, no matter whose it is. My most difficult experiences have continued to be translating very negative, almost visceral, reactions into sensible criticism. Many years and hundreds of reviews later, I still feel challenged when faced with the twin tasks of judging and then explaining, clearly and succinctly, the reasons for a judgment. I persist because of a very deep conviction that (Note to the printer: please set the following in 18pt. Whatever Bold)

A PICTURE BOOK IS A COMPLICATED FORM OF COLLABORATIVE ART.

When it is very well done, it is an artistic achievement worthy of respectful examination and honor. Even failures, and especially near misses, deserve the kind of attention and understanding given to serious creative endeavors.

Picture books do not get this often enough. Like children, they are short, and often condescended to by people who, because they do not spend much time with them, do not know better. Have I ever been at a dinner party where someone, hearing what my work is, has not offered to share with me his or her "great idea for a kids' book"?

"A few hundred words . . . a handful of pages . . . I can do that" is the common, if unspoken, belief hovering in the air between us.

Just a few hundred words? No problem, right? Then let us begin with them. Like poetry, a picture book has to be written in two ways. It must work when read aloud, and also when read silently to oneself. Every syllable counts. Most important, the well-chosen words need to be simple but never simplistic, clear and strong enough to interest a child and hold her attention. Style alone is not sufficient. When Isaac Bashevis Singer won the Nobel Prize for Literature he announced that there were "five hundred reasons why I . . . write for children." One was that, "they still believe in God, the family, angels, devils, witches, goblins, logic, clarity . . . " Another was: "They love interesting stories." Short, interesting stories are the structural steel that supports the illustrations in picture books. Look up "illustrate" in a Webster's Unabridged. The root is illustrare. And among the definitions are "to light up, illuminate, embellish, shed light upon, to throw the light of intelligence upon, to make clear, to elucidate by means of a drawing or pictures." And all that is just what wonderful illustrations do, and have done ever since books were first illuminated in medieval times by talented, cloistered hands.

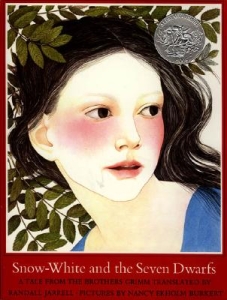

In 1972, Nancy Ekholm Burkert began her illustrated version of "Snow White" by illuminating the O in the word Once. "Once it was the middle of winter, and the snowflakes fell from the sky like feathers." These are the first words of the Randall Jarrell translation. The type starts three quarters of the way down a large white page. A bare tree stands behind the decorated "O." A hunter and his dog step through it into the fairy tale. The reader follows, drawn by the pictures into the story, by the story into the pictures. It is this always-changing relationship of words and pictures that makes and shapes picture books.

In 1972, Nancy Ekholm Burkert began her illustrated version of "Snow White" by illuminating the O in the word Once. "Once it was the middle of winter, and the snowflakes fell from the sky like feathers." These are the first words of the Randall Jarrell translation. The type starts three quarters of the way down a large white page. A bare tree stands behind the decorated "O." A hunter and his dog step through it into the fairy tale. The reader follows, drawn by the pictures into the story, by the story into the pictures. It is this always-changing relationship of words and pictures that makes and shapes picture books.About 1200 to 1500 of these slim volumes are published in a year that approximate figure includes fiction, nonfiction, and board books. Most of these are noted at least once, a few lines to a customer, in a couple of professional journals. A very small percent of the books published will receive more than two or three hundred words of public recognition. A talented, highly regarded editor of my acquaintance suggests testing even the more extensive reviews by crossing out any analytical comments with your pen to see what is left. The result? Even the longer reviews turn out to consist almost completely of plot summary. In the days of color overlays, this editor added, one journal consistently used slight variations of the same last line to comment on the art, "the pictures are done in striking shades of melon, pimento, and avocado." Can a plot summary or an appraisal, more suitable to a discussion of lunch, really be all there is to say about thirty-two pages of graphic drama starring pictures and words?

Two clichés may help explain why so few picture book reviewers study the form they are dealing with and its history. The first, "it's just a kids' book," is not usually articulated but relates to an old bias toward childhood. The other, heard too often, is "I don't know much about art but I know what I like." The problem with this one is that a critic not only needs to know what she likes, she also has to be able to say why. Know-nothing attitudes are at least partially responsible for the short shrift or "plot summary" school of picture book criticism.

In fact, there is more to learn about art, and that includes the art of illustration, than most of us will absorb in a lifetime. Looking at the work of a fine illustrator, we see, as we do when we examine fine painting or sculpture, a particular vision drawn from styles and techniques of past and present, filtered through a single sensibility. The period relevant to contemporary picture books began with the advent of modern printing, about ninety years ago. There have been wonderfully creative people at work over this time. And the more familiar one is with their output, the more discriminating one becomes. Without this background it is much more difficult for a critic to recognize original, new talent. Or to differentiate between the fresh skill in little book A as contrasted with the competent but very derivative little book B.

Many years ago, I was invited as a poet in brief residence to help introduce some classes of eight-, nine-, and ten-year-olds to writing and poetry. Working two weeks at a time over a four-year period, I found an effective starting point for those young writers that, considered in retrospect, may also be applicable to critical writing. The students and I talked then about the differences between looking and seeing. How important it is when you are writing, and drawing, to really pay attention: to see. The first assignment I gave them was to write a description of a thing. This was an exercise in using words with precision, to convey a picture of something the writer might have looked at, perhaps often, but not really paid close attention to. I wanted these students to make pictures with words so accurately that whoever read them would see what the children had seen. Gretchen described her running shoes in a paragraph. Henry studied the picture over his bed and wrote about it with care. Sara captured her favorite stuffed animal on paper. And when we read these descriptions to one another, it became obvious that many of them contained feelings about the thing being described. Sharp observation, we deduced, often goes hand in hand with personal response and judgment.

Another point my students and I discussed is also relevant here. I asked them not to be satisfied with describing something as "nice" or "pretty." Instead I told them to be specific, and use details to explain how some place or thing was special. In a tribute to James Marshall, his friend Maurice Sendak has written, "[He] was . . . entirely himself . . . uncommercial to a fault . . . . He paid the price of being maddeningly underestimated — of being dubbed ‘zany’ (an adjective that drove him to muderous rage.)" Zany is one of those inexact, nondescriptive adjectives like pretty, nice, and wacky; the last, a label stuck on the charmingly complex compositions of William Joyce. Reviewing his book Santa Calls, I attempted a mini-analysis of its charm.

The author’s acknowledgments to "Robin of Locksley, Nemo of Slumberland, and Oz, the first Wizard Deluxe" alert us to a few of the artistic ghosts that influence these pages. . . . This is Spielberg territory, full of homages to beloved clichés. . . . Mr. Joyce is meticulous and wily. Each of his elegantly painted illustrations is set up, costumed, and lit with a cinematographer’s eye. . .

But are the thirties film touches in an artist’s style or a feeling that his work is "underestimated" meaningful to a child? And if they are not, then why bother with such specifics in a review of a book for children?

Ursula Nordstrom, one of the most noted and creative of the grand old generation of children’s book editors, used to insist that if you put a child happily in your lap and read the phone book to her, she would be delighted. After all, nobody is born with taste, either good or bad. When a beloved parent or a teacher espouses something new, the odds are that the children close to that parent or teacher will be pleased with it, too. But, both bookmakers and their critics have responsibilities as taste-makers and therefore as educators. That is why it is in a critic’s job description to point out when the wit in a story is not evident in the art, or the drawing of the central figure is an awkward knockoff of something Arthur Rackham did better. Even though the child the book is meant for will not necessarily see these fine points, someday when he is picking out books for his own child he will be more discriminating, in part because you and I have been.

Re-reading these last paragraphs I realize that I seem to have stressed the importance only of an educated eye for a wise appreciation of picture books. Obviously, intelligent criticism of such a true combination form must give equal time to the words that provide the book’s skeleton. But because so many teachers, librarians, and scholars are devoted readers with cultivated literary points of view, I am making the assumption that the written word is not neglected or misunderstood as often as illustration is.

A contradictory note here is that when picture book prizes are being handed out, it is the words that are frequently overlooked. The major medals are almost always awarded to the illustrator alone. If you have ever been a judge on such a jury — with hundreds of books to winnow away before one gets down to the preprize stack — you know that judges don’t have time to read most of the books but simply riffle through acres of pages searching for striking art. And yet, that excellent illustrator and lover of words Arnold Lobel once compared illustrating with another interpretive art, the work of an actor learning a new role. "You read a manuscript a hundred thousand times," he sighed, explaining how he approached his job. In an ideal picture book world, why would anyone separate prize-winning illustrations from the words that have made them prize-winning?

And in the same ideal world, humor and simplicity, two arts that depend on artlessness, would receive the attention they deserve. Some years ago, writing about James Stevenson’s work, I commented on the fact that "understatement is often overlooked when awards are given to picture books." A book I referred to especially is July (1990). It is based on childhood recollections, and in it Stevenson achieves "the essence of photographs, in wash drawings . . . .Scenes are reduced to essentials with a calligrapher’s appreciation for each brush stroke. They record the heart of things so minimally but so tellingly that we are able to recognize the children as ourselves and the memories as our own." Too many critical (but not critical enough) eyes are impressed by self-proclaimed ART, overinflated, glossy work reflecting the graphic fashion of the moment but with little either personal or unique to recommend it. Spend some time with the work of Marc Simont, William Steig, Jon Agee, and Tomi Ungerer to appreciate the artists gifted with the ability not only to draw but to draw funny. And never forget the wonderfully careful hand and refreshing vision of Crockett Johnson. The creator of Harold and his adventurous purple crayon and of the classic comic Barnaby, and illustrator of Ruth Krauss's The Carrot Seed, never won a prize, but left the world a better place anyhow. Surely someone, somewhere, could award him, in absentia, the first platinum Carrot for quietly sustained, imaginative humor.

And in the same ideal world, humor and simplicity, two arts that depend on artlessness, would receive the attention they deserve. Some years ago, writing about James Stevenson’s work, I commented on the fact that "understatement is often overlooked when awards are given to picture books." A book I referred to especially is July (1990). It is based on childhood recollections, and in it Stevenson achieves "the essence of photographs, in wash drawings . . . .Scenes are reduced to essentials with a calligrapher’s appreciation for each brush stroke. They record the heart of things so minimally but so tellingly that we are able to recognize the children as ourselves and the memories as our own." Too many critical (but not critical enough) eyes are impressed by self-proclaimed ART, overinflated, glossy work reflecting the graphic fashion of the moment but with little either personal or unique to recommend it. Spend some time with the work of Marc Simont, William Steig, Jon Agee, and Tomi Ungerer to appreciate the artists gifted with the ability not only to draw but to draw funny. And never forget the wonderfully careful hand and refreshing vision of Crockett Johnson. The creator of Harold and his adventurous purple crayon and of the classic comic Barnaby, and illustrator of Ruth Krauss's The Carrot Seed, never won a prize, but left the world a better place anyhow. Surely someone, somewhere, could award him, in absentia, the first platinum Carrot for quietly sustained, imaginative humor.A parenthetical thought on illustrative art: I am not convinced that the medium is really the message. Of course, if you know what gouache is and can tell it from transparent watercolor or acrylic, then you, and I, will find it enlightening to read about such details. However, if you, like the majority of readers, are not familiar with artists' materials and techniques, learning that a picture is done in Prisma color and croquil line is not really helpful — better for a critic to explain that the delicately rendered scenes are sketched in fine pen line and softly shaded colored pencil, thus making it easier for nonexperts get a little more of the picture.

Because reviews of a picture book are not written for the book's orimary audience but rather for teachers, librarians, and other interested adults with wallets, the critic, like the book's author, needs a dual perspective. First, her own perception and standards, and second, that of the book's young viewers and listeners. How will the sounds and rhythms of a narrative impress the ears of nonreaders? And will the life and action of the art appeal to a child's observant eyes?

Back in 1959, in a picture book called Just Like Everyone Else, I cast a small soft dog as a special friend for sharp-eyed nonreaders to follow through the story. Although the dog was rarely mentioned in the text, he appeared on every page, quietly, uh . . . dogging the action. I was sure that I had made an excellent discovery in using him this way. Since then I have become familiar with a lively, bursting world of minor players in picture books. Caldecott was a master of them; Mussano used cats in the opening chapters of his 1911 edition of Pinocchio; small, silent players have enlivened works by Ardizzone, Seuss, Margot Zemach, and countless others. Not to mention the hop-, scamper-, and walk-ons in all those Disney films.

Over the years that have passed since I did my first book for children (Roar and More, 1956), I have written, read, illustrated, and concentrated my attention in and around this fruitful field. But in trying to frame some coherent final thoughts on reviewing, I have arrived at only one obvious conclusion: there is always more to learn. The history of illustrated books is long and wide. But each new volume, whether it is awful, amazing, or, most usually, somewhere in-between, requires the critical ability to recognize what is old, to appreciate what is new, and to exercise faith in one's own judgment. Samuel Butler, who specialized in saying things better than the rest of us, said this better, too. "The test of a good critic is whether he knows when and how to believe on insufficient evidence."

From the March/April 1998 issue of The Horn Book Magazine: Special Issue: Picture Books.

RELATED

RECOMMENDED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!

Joy Chu

It's a boost to the spirit, when you start the day reading a Karla Kuskin poem. When did she originally write this? I know she passed away in 2009...Posted : Nov 20, 2012 07:00

Sergio R.

I miss her.Posted : Nov 19, 2012 11:08