The CCBC's Diversity Statistics: A Conversation with Kathleen T. Horning

The Cooperative Children’s Book Center (a research library of the University of Wisconsin–Madison School of Education) began documenting the numbers of children’s books by African American authors and illustrators in 1985 — when then–CCBC director Ginny Moore Kruse, serving on the Coretta Scott King Book Awards Jury, learned that of the approximately 2500 trade books published that year, only eighteen had been created by African Americans.

Kathleen T. Horning

Kathleen T. HorningThe Cooperative Children’s Book Center (a research library of the University of Wisconsin–Madison School of Education) began documenting the numbers of children’s books by African American authors and illustrators in 1985 — when then–CCBC director Ginny Moore Kruse, serving on the Coretta Scott King Book Awards Jury, learned that of the approximately 2500 trade books published that year, only eighteen had been created by African Americans. In 1994, the CCBC added the publishing statistics for books by Asian/Asian American, Latinx, and First/Native Nations book creators (and for the first time included books not just by but about African Americans). This year’s statistics were released in February. (To see the entire study, visit https://ccbc.education.wisc.edu/books/pcstats.asp.) Current CCBC director Kathleen T. Horning was gracious enough to answer a few questions about the past, present, and future — both of the CCBC study and of books by and about people of color.

Martha V. Parravano: This year marks thirty-two years of gathering these statistics. What kept you going through the decades where the lack of progress must have made it feel like nobody was listening?

Kathleen T. Horning: We felt a strong commitment to document the numbers from the beginning. They spread like wildfire by word of mouth, so we did hear from people back in the 1980s, usually via telephone. Philip Lee of Lee & Low, for example, called us to verify our statistics for their business plan when they were just getting started. They used the statistics to make the case for the great need for more diverse books. And at professional conferences, Ginny Moore Kruse and I both had the experience of having the statistics quoted back to us from people who didn’t know we were the original source. Then in 1989 USA Today carried a big story that used the stats from the first four years, and that was widely syndicated. After that we became known as The Source for both the press and academic researchers.

MVP: Looking just at the numbers, we should not be celebrating, right? I mean, back in 1985, eighteen out of 2500 children’s books were by African Americans (.007%); now in 2016, it’s ninety-two out of 3400 (.03%). That’s not a huge increase, percentage-wise.

KTH: True. We saw a small bump back in the late 1980s; after that, the numbers have plateaued and have been pretty stagnant ever since. Walter Dean Myers wrote a really perceptive and hard-hitting essay about this phenomenon for The New York Times back in 1986 called “I Actually Thought We Would Revolutionize the Industry.” Unfortunately, everything he said then is still pertinent today, thirty-one years later.

MVP: Yes, and you could say the same thing about Jacqueline Woodson’s 1998 Horn Book article “Who Can Tell My Story,” which basically called for #ownvoices. Nineteen years ago. Are you seeing any effect yet of the #ownvoices movement? More books “about” being also “by”?

KTH: Unfortunately, not yet. But considering how long it takes a book to go from inception to publication, it would be pretty early for that unless things were being rushed to market, which I don’t see happening. In the past few years we’ve seen a dramatic increase in the books about, though, particularly for books about (but not by) African Americans.

MVP: There seems to have been quite a jump this year in the number of books by Asian and Asian American authors and illustrators.

KTH: We’ve seen an enormous uptick in books by Asian Americans, but most of these are not specifically about Asians. Think, for example, of two books by Asian Americans that won ALA awards and honors in 2015: The Adventures of Beekle (by Dan Santat) and This One Summer (by Mariko Tamaki and Jillian Tamaki). Neither featured visible Asian characters. This is par for the course right now. Of the 212 books published by Asians/Asian Americans last year, only seventy-five (35%) were about Asian characters. That means that about 65% of the books by Asians/Asian Americans published in 2016 were not about Asians. You can put a positive spin on this and point out that means some Asian authors are being given the freedom to write whatever they want. But that also means almost two-thirds of the books about Asians are being created by non-Asians. That’s not really #ownvoices.

MVP: Interesting, because that’s not obvious from the numbers. The numbers just say that 212 are by Asian Americans and 237 are about Asian Americans.

KTH: It can be tricky to parse that out. We have always kept author/title logs that make all of this clearer because they specify books by but not about, books about but not by, and books both by and about. We need to find a better way to represent these kinds of totals in our online graphs, but right now we don’t really have the personnel to do all of that. It would be a full-time job for someone. So, while there were 212 books published in 2016 by Asians/Asian Americans, 137 of them were not about Asian or Asian American characters. It would break down like this:

Total number of books about Asians/Asian Americans: 237

Total number of books by Asians/Asian Americans: 212

Total number of books by and about Asians/Asian Americans: 75

Total number of books about but not by Asians/Asian Americans: 162

These numbers are more apparent in a Venn diagram:

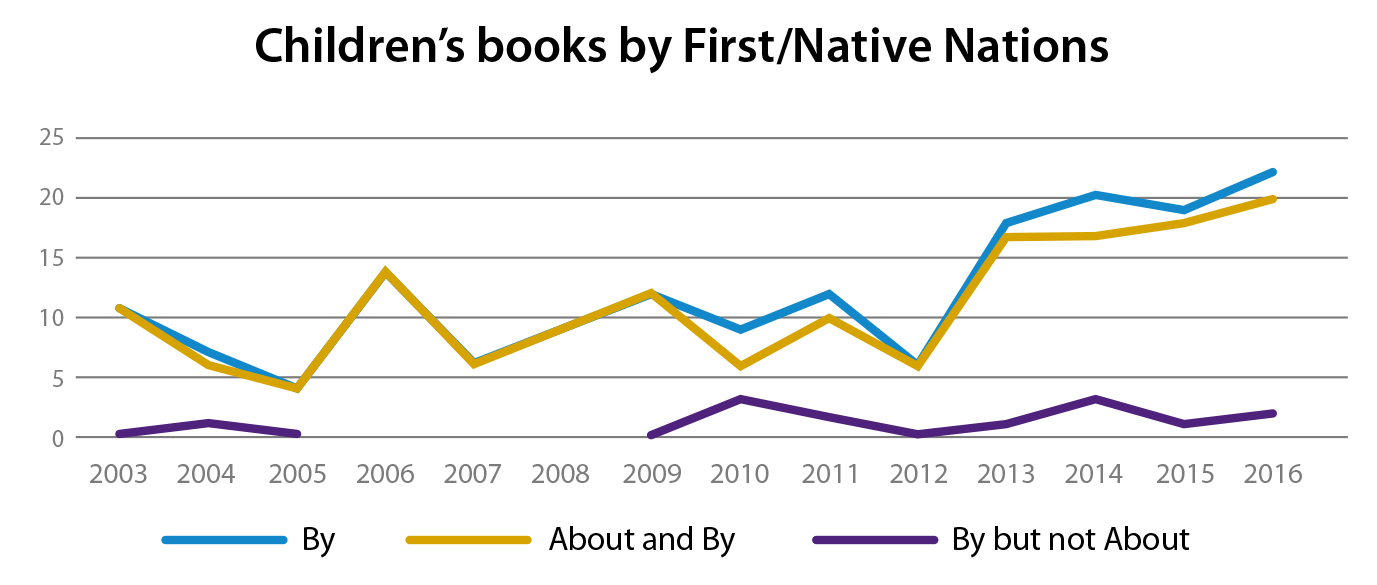

MVP: Any insight into what is happening with First/Native Nations books? The by/about numbers look fairly stagnant.

KTH: The numbers over time for books by and about First/Native Nations tell an interesting story. In 2003, a whopping 88% of the books were created by non-Native writers and illustrators. That number plummeted the following year and has held steady since then at about 60%. I believe that is due to the hard-hitting criticism from the Native organization Oyate and, more recently, Debbie Reese at her blog American Indians in Children’s Literature. They have made authors and publishers aware of how little outsiders generally know about individual Native nations, or First/Native Nations in general. We don’t have that same consistent level of cultural criticism for books about African American, Asian/Asian American, and Latinx people.

MVP: As you state in your report, you don’t take quality into account. But does it matter that so many excellent books by people of color are being published and winning awards if the numbers are still so low?

KTH: I hope that award winners like Linda Sue Park, Rita Williams-Garcia, Kwame Alexander, Matt de la Peña, and Javaka Steptoe are paving the way for new authors and illustrators of color to be published. I get the sense that many editors are actually looking for those fresh and authentic voices. Certainly literary agents such as Regina Brooks, Adriana Domínguez, Barry Goldblatt, and Jennifer Laughran have been vocal advocates for new authors of color. That’s a hopeful sign that they believe the demand is there from the publishers. And breaking through that first barrier into the publishing world is generally the biggest obstacle an author or illustrator faces, aside from creating a kick-ass book, of course.

MVP: Tell me about the increase of picture books you’ve noted featuring brown-skinned characters. It seems like a positive development, overall…but do you worry about publishers (and the rest of us) thinking our “diversity quota” has been filled if we have these picture books?

KTH: This year we have launched a pilot study where we’re looking at more in-depth diversity statistics with a focus on picture books. So we’re keeping track of not just race and ethnicity but species (human, animal, other), gender, disability, LGBTQ, and secondary characters. When we started taking a really close look, we realized there were many picture books with brown-skinned characters where it was impossible to determine their race, either from the illustration of the characters themselves or from any cultural markers in the text or illustration. These characters could be African American, Latinx, Asian, First/Native Nations, or biracial. I suppose you could even make a case for some of them being white, with dark hair and eyes and light-brown skin. We’ve been keeping track of diversity statistics for thirty-two years and have never seen this extent of ethnically vague characters. I suspect that this might be the immediate response to #weneeddiversebooks, where illustrators are deciding or being encouraged to darken their protagonists. Is that a good thing? If the books are really good, yes. But if publishers feel they’re meeting some sort of “diversity quota” with these sorts of books, and are publishing them in lieu of books by people of color, I’m not so sure.

MVP: What will be your protocol for counting these books? Since the whole point really is how indefinite the characters’ backgrounds are.

KTH: Most of the picture books about people are pretty clear on race, and the vast majority of them have white protagonists. But it’s not always easy to tell, which is why we created the “brown-skinned” category. We also have a “multicultural” category for books like Christian Robinson’s new edition of The Dead Bird, which has a multiracial cast with no clear leading character, and another for biracial protagonists, which we generally see when there are clearly interracial parents shown. The breakdown for picture books with human characters in 2016 looks like this:

Picture books about people (U.S. publishers only)

White: 319

Multicultural: 59

African American: 46

Brown-skinned: 42

Asian/Asian American: 30

Latinx: 20

Biracial: 10

First/Native Nations: 2

MVP: So that’s approximately 62% human white characters; 41% everyone else! It will be fascinating to track these figures, going forward. Do you have any expectations/predictions for the future?

KTH: Our numbers also showed that 48% of the picture books we received were about people, 41.5% were about animals, and 13.5% were about “other”—trucks, crayons, trees, cupcakes, a carton of milk, etc. (The numbers add up to more than 100% because some books show both, e.g., a human interacting with a talking animal character.) Personally, I’d like to see fewer books about animals standing in for humans — how many talking bunnies do we really need? But if we’re going to continue to see less than half of picture books being about people, there needs to be more diversity in the human characters we do see in picture books. I hope that will begin to happen, and that more of them will be created by authors and illustrators of color and First/Native Nations.

MVP: What has been the impact of social media in terms of getting the information out there? These statistics must be exponentially more widely distributed than in previous decades.

KTH: The numbers are everywhere on social media these days. I think the impact has been making people think on a daily basis about the lack of progress in diversity when it comes to books for children and teens, even as our society becomes increasingly diverse. More importantly, there are authors, critics, and scholars of color who are tweeting and blogging about these issues all the time. Everyone can learn from this exchange of observations and ideas.

There’s so much more that can be done if we look more deeply into the numbers in terms of examining what is — and isn’t — being published. How many of the books by First/Native Nations writers are being published by small Canadian presses versus large U.S. publishers (answer: most), and why is that? How many of the books about African American males deal with sports or jazz musicians, and what does that say about what we value? Why do so many Asian authors choose not to write or illustrate Asian characters? How are we nurturing the next generation of authors and illustrators who will follow in the footsteps of book creators like Jason Reynolds and Yuyi Morales? We know they are out there right now, sitting in (most likely) public-school classrooms. What are they seeing in the books they’re reading?

Author/illustrator Yuyi Morales browses the CCBC collection.

Author/illustrator Yuyi Morales browses the CCBC collection.Kathleen T. Horning is the director of the Cooperative Children’s Book Center, a library of the School of Education, University of Wisconsin–Madison. She is the author of From Cover to Cover: Evaluating and Reviewing Children’s Books and teaches a popular online course for ALSC on the history of the Newbery and Caldecott medals.

Martha V. Parravano is book review editor of The Horn Book, Inc. She is currently serving on the 2017–2019 Coretta Scott King Book Awards Jury and just finished judging for the Los Angeles Times Book Prize for Young Adult Literature. She learned pretty much everything she knows about children’s books at the CCBC.

RELATED

RECOMMENDED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!

Nick Bruel

Tabitha, if I may... pretty much everything you state is true. I won't contradict you. But such is the pitfall of choosing a creative following, whether it be writing, illustrating, acting, dancing, and so on. Maybe there really are those who hit gold early on and can support themselves comfortably. But that are rare creatures, indeed. Most of us scrimp and save and sacrifice constantly to devote ourselves to our career. I don't know of ANYONE who ever said, "I'm going to be a children's book author, because that's where the money is!" It's not easy, and the payoff is dicey at best, especially in the beginning. And I wish I could tell you that luck isn't a factor, but it is. Having said that, persistence is an even bigger factor. No amount of luck in the world will do any good unless you devote yourself with every fiber of your being to the work itself. Invest in yourself, and you'll be fine. Good luck.Posted : Aug 09, 2017 12:22

Tabitha

Recently, I met a few juvenile book agents at BEA. One said they would only see my work if I signed up for a critique at a big conference they were at. Considering the costs, that would be my rent and bills to maybe get an agent. The agents all basically said it’s hard to make money at being an author. I will not be sending these agents my work. If I am heading into a career to build myself up and the agents are singing the poverty tune, being an author (and agents who can’t make money) do not fill me with any enthusiasm for a career field which can help me rise economically. The only ones who can afford this career are those who are rich, or are retired with a pension, or have other financial support or another job. The books creatives are told to find a spouse with insurance! My artist friend who is popular in kids books these day said the illustrators are getting part time jobs to support their publishing careers. It seems from my POV the only one’s making a living at kids book publishing are those that talk about the books and not the book creators themselves. Even editors, art directors, agents, librarians, and insider book professionals are getting the book contracts these days. Why would anyone looking to better themselves, who are not rich nor have other financial support, want a career that spells poverty? Be real.Posted : Aug 07, 2017 10:25

Heidi Rabinowitz

Thank you for expanding the scope of your statistic-keeping. I'd also love to see you add a religion category. Personally, I'm interested in the numbers on books featuring Jewish characters.Posted : Mar 30, 2017 02:28

Demo

Taking these numbers on their face and comparing them to the 2010 USA census is telling. Number of picture books in the USA about people: 511. Number of them about white people: 319. Percentage of them about white people: 62.4%. Percentage of the USA population that is white, according to 2010 census statistics: 63.7%. Percentage about Asians and Asian-American: 5.8%. Percentage of USA population that is Asian: 3.6% Whites slightly underrepresented on percentage basis, Asians over-represented. African-Americans underrepresented, but the new "multicultural" category (better, non-designated non-white, since many multicultural children are white in color but non-dominant culture in culture) may skew the percentage for non-whites. http://www.infoplease.com/ipa/A0762156.html has the census figures.Posted : Mar 28, 2017 11:30