Robert McCloskey at 100

Robert McCloskey was to the mid-twentieth-century American picture book what Norman Rockwell was to the illustrated magazine of that era: the artist most adept at divining the mythic dimension in the dramas of everyday life, and at crafting iconic images of a particular time and place with the power to stir and delight generations.

Robert McCloskey was to the mid-twentieth-century American picture book what Norman Rockwell was to the illustrated magazine of that era: the artist most adept at divining the mythic dimension in the dramas of everyday life, and at crafting iconic images of a particular time and place with the power to stir and delight generations. McCloskey, who was born in Hamilton, Ohio, one hundred years ago this September 15th (and who died in Maine in 2003 at age eighty-eight), made his initial mark as the author and illustrator of Lentil, a picture book that recast his childhood home as the epitome of small-town America. Published in 1940 at the tail end of the Great Depression, Lentil was already a wistful work when new, and in that regard a kind of picture-book counterpart to Laura Ingalls Wilder’s contemporaneous Little House books. Nearly three-quarters of a century later, it remains of interest as a nimble vignette of good-natured resourcefulness and community spirit, and as the journeyman effort of an artist just learning to turn the straw of mundane observational reality into picture book gold.

Robert McCloskey was to the mid-twentieth-century American picture book what Norman Rockwell was to the illustrated magazine of that era: the artist most adept at divining the mythic dimension in the dramas of everyday life, and at crafting iconic images of a particular time and place with the power to stir and delight generations. McCloskey, who was born in Hamilton, Ohio, one hundred years ago this September 15th (and who died in Maine in 2003 at age eighty-eight), made his initial mark as the author and illustrator of Lentil, a picture book that recast his childhood home as the epitome of small-town America. Published in 1940 at the tail end of the Great Depression, Lentil was already a wistful work when new, and in that regard a kind of picture-book counterpart to Laura Ingalls Wilder’s contemporaneous Little House books. Nearly three-quarters of a century later, it remains of interest as a nimble vignette of good-natured resourcefulness and community spirit, and as the journeyman effort of an artist just learning to turn the straw of mundane observational reality into picture book gold.Prior to McCloskey’s rise to prominence as an author in the 1940s, the writer most closely identified with Hamilton, Ohio, was William Dean Howells, the nineteenth-century novelist, critic, magazine editor, and friend of Mark Twain. Howells spent eight apparently happy years during the 1840s growing up under the spell of the up-and-coming river and market town. A memorable phrasemaker, he recalled Hamilton as a place “peculiarly adapted for a boy to be a boy in.” Nearly a century later, as McCloskey sketched Lentil ’s rustic clapboard storefronts, churches, houses, and Tom Sawyer–ish whitewashed fences, he seems to have had the idyllic Hamilton of Howells’s boyhood in mind at least as much as he did the latter-day manufacturing city that he himself had known, with its massive factories and paper mills that dominated the local economy and polluted the once swimmable Great Miami River.

McCloskey was a storyteller, not a historian, of course, and as he reimagined Hamilton first as Lentil’s Alto and later as the Centerburg of Homer Price and its sequel Centerburg Tales, he scaled down nearly all the city’s major landmarks to more closely conform to an idealized — perhaps an East Coast publisher’s — fantasy of modest, homespun, small-town Midwestern life. In McCloskey’s drawing of the Alto public library, for instance, he opted for a boxy generic design instead of the architecturally more distinctive profile of Hamilton’s Lane Public Library’s fashion-forward 1866 octagonal structure. (The original building, long since expanded, remains in use today.) A few blocks away, Hamilton’s towering Soldiers, Sailors & Pioneers Monument is bound to surprise the visitor who has long held McCloskey’s much humbler version in his or her mind’s eye. The real monument’s impressive architectural base houses an interior chamber that features a display of war relics. McCloskey’s pint-sized memorial is a different affair, a mildly irreverent caricature of a monument consisting of a sculpted sailor, goddess, artilleryman, and cannon all perched atop a standard-issue column.

In only one instance did McCloskey reverse the whittling-down process. To highlight the power and wealth of the story’s returning hero Colonel Carter, he gave the red-brick Federal-style Hamilton home that served as his model for the colonel’s house an imposing new mansard roof and dressy gingerbread trim. Not only that, the top-hatted mayor who greets the great man at the train depot is none other than McCloskey himself. Lentil is McCloskey, too, of course, although (as the artist later told interviewers) he himself had never walked Hamilton’s streets barefoot; his no-nonsense mother, Mabel Wismeyer McCloskey, would never have allowed it. His father, Howard Hill McCloskey, was a manager at a local canning factory. He had a talent for mechanical invention that his son took pride in having inherited. Homer Price, boy inventor in the Tom Swift/Stratemeyer Syndicate series mold, was every bit as much a self-portrait as was Lentil, boy harmonica player. As a schoolchild, McCloskey had alternately imagined growing up to become an engineer or a musician until, as a teenager, he shifted his allegiance to the visual arts. Butler County historian Thomas F. Stander attributes the fateful change to the influence of the boy’s paternal grandfather, a local photographer “who encouraged him and bought him materials.” John B. McCloskey maintained a photography studio along a busy shopping street at the center of town, where “he did small landscapes and flowers, like those done in the 1890s. These sold at church socials or were given to friends.” According to Stander, young Bob not only frequented his grand-father’s studio but also found in the elder McCloskey’s feeling for aesthetic concerns a much-needed antidote to his pious Protestant mother’s dour view of art as “frivolous.”

In only one instance did McCloskey reverse the whittling-down process. To highlight the power and wealth of the story’s returning hero Colonel Carter, he gave the red-brick Federal-style Hamilton home that served as his model for the colonel’s house an imposing new mansard roof and dressy gingerbread trim. Not only that, the top-hatted mayor who greets the great man at the train depot is none other than McCloskey himself. Lentil is McCloskey, too, of course, although (as the artist later told interviewers) he himself had never walked Hamilton’s streets barefoot; his no-nonsense mother, Mabel Wismeyer McCloskey, would never have allowed it. His father, Howard Hill McCloskey, was a manager at a local canning factory. He had a talent for mechanical invention that his son took pride in having inherited. Homer Price, boy inventor in the Tom Swift/Stratemeyer Syndicate series mold, was every bit as much a self-portrait as was Lentil, boy harmonica player. As a schoolchild, McCloskey had alternately imagined growing up to become an engineer or a musician until, as a teenager, he shifted his allegiance to the visual arts. Butler County historian Thomas F. Stander attributes the fateful change to the influence of the boy’s paternal grandfather, a local photographer “who encouraged him and bought him materials.” John B. McCloskey maintained a photography studio along a busy shopping street at the center of town, where “he did small landscapes and flowers, like those done in the 1890s. These sold at church socials or were given to friends.” According to Stander, young Bob not only frequented his grand-father’s studio but also found in the elder McCloskey’s feeling for aesthetic concerns a much-needed antidote to his pious Protestant mother’s dour view of art as “frivolous.” Drawing by Marc Simont of studio-mate and best friend Robert McCloskey, circa 1939. (McCloskey is repairing a camera with what looks like a Bowie knife.)

Drawing by Marc Simont of studio-mate and best friend Robert McCloskey, circa 1939. (McCloskey is repairing a camera with what looks like a Bowie knife.)Once he chose his direction, the tall, lumbering teenager appears to have resolved, like the great turn-of-the-twentieth-century Chicago architect Daniel Burnham, to “make no little plans.” While working as a counselor at YMCA Camp Campbell Gard, north of Hamilton, during the summers of 1930 and 1931, McCloskey carved a five-hundred-pound cedar log into a totem pole that for sixty years remained an area landmark. (The massive pole and other original art and memorabilia have now been brought together in a small Robert McCloskey Museum housed within Hamilton’s Heritage Hall.)

In 1932, as a seventeen-year-old, he enjoyed a second flurry of local renown as the designer of an ambitious George Washington Bicentennial calendar. He capped his high school career by winning the Scholastic Young Artists Award scholarship that paved his way for enrollment at Boston’s Vesper George School of Art the following year. As McCloskey recalled in my 1991 interview with him, “The Depression had begun, and but for that scholarship I think I would never have been able to set foot out of the state of Ohio.” Then in 1934, Hamilton honored the young man again with a plum commission for the bas-reliefs, stained-glass window designs, and other decorative elements for its new Art Deco–style Municipal Building (now Heritage Hall). He completed the project during the time he was studying in Boston, where he continued to prepare himself for a career as a print maker and painter and came to realize that an artist had to be ready to try just about anything.

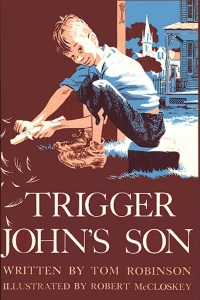

McCloskey’s closest childhood friend (and in later years, his family lawyer) was Stuart M. Fitton, a member of a prominent Hamilton banking and manufacturing family. When McCloskey felt ready to show his portfolio to potential illustration clients in New York, the Fittons directed him to Stuart’s aunt — a sister of Stuart’s mother who had made quite a name for herself in publishing circles, Viking editor May Massee (Stuart’s middle initial stood for “Massee”). Massee had a warm welcome in store for the young visitor from Hamilton. She hired McCloskey on the spot to create a new book jacket for Tom Robinson’s novel Trigger John’s Son and — auspiciously, as it turned out — she treated him that rain-soaked evening to a roast duck dinner. Massee also had pointed advice for her still-green though clearly talented visitor. She admonished him, he later recalled, to “get wise” to himself and to “shelve the dragons, Pegasus” and other “great art” images he had brought along for her inspection. She urged him to draw and paint what he knew. Taking her good counsel to heart, he signed up for drawing classes at the academically rigorous National Academy of Design, in New York, and then returned for a time to Hamilton — the place he knew best of all — where he made the sketches that culminated in Lentil. The rest, one might be tempted to say, is history — except that history was not the half of what Lentil was really about for him. The rest of the rest was fiction: pure spun-gold Robert McCloskey storytelling.

McCloskey’s closest childhood friend (and in later years, his family lawyer) was Stuart M. Fitton, a member of a prominent Hamilton banking and manufacturing family. When McCloskey felt ready to show his portfolio to potential illustration clients in New York, the Fittons directed him to Stuart’s aunt — a sister of Stuart’s mother who had made quite a name for herself in publishing circles, Viking editor May Massee (Stuart’s middle initial stood for “Massee”). Massee had a warm welcome in store for the young visitor from Hamilton. She hired McCloskey on the spot to create a new book jacket for Tom Robinson’s novel Trigger John’s Son and — auspiciously, as it turned out — she treated him that rain-soaked evening to a roast duck dinner. Massee also had pointed advice for her still-green though clearly talented visitor. She admonished him, he later recalled, to “get wise” to himself and to “shelve the dragons, Pegasus” and other “great art” images he had brought along for her inspection. She urged him to draw and paint what he knew. Taking her good counsel to heart, he signed up for drawing classes at the academically rigorous National Academy of Design, in New York, and then returned for a time to Hamilton — the place he knew best of all — where he made the sketches that culminated in Lentil. The rest, one might be tempted to say, is history — except that history was not the half of what Lentil was really about for him. The rest of the rest was fiction: pure spun-gold Robert McCloskey storytelling.Grateful acknowledgment is made of the generous help of the following individuals who furnished important background information for use in this article, much of it based on their own research: Thomas F. Stander (Butler County historian), Gratia Banta (youth services manager, the Lane Libraries), Brandon Soale (curator, Heritage Hall and the Robert McCloskey Museum), Jim Schwartz, and Sam Ashworth.

From the September/October 2014 issue of The Horn Book Magazine.

RELATED

RECOMMENDED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy: