2018 School Spending Survey Report

Nancy Drew and Her Rivals: No Contest (Part I)

If imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, then Harriet S.

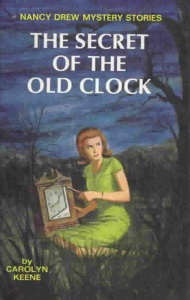

If imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, then Harriet S. Adams may have been, next to Hemingway, the most sincerely flattered author of the 1930s. Though her father, Edward Stratemeyer, founder of the Stratemeyer Syndicate, originated the Nancy Drew mystery series with three books published shortly before his death in 1930, thereafter, according to Adams, Nancy Drew was her own personal project.

If imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, then Harriet S. Adams may have been, next to Hemingway, the most sincerely flattered author of the 1930s. Though her father, Edward Stratemeyer, founder of the Stratemeyer Syndicate, originated the Nancy Drew mystery series with three books published shortly before his death in 1930, thereafter, according to Adams, Nancy Drew was her own personal project.It was a project that lit a beacon in the publishing world. Even before 1934, when Nancy Drew outsold every other juvenile title on the Christmas book list, new girl sleuth series had begun to multiply, most of them bearing a remarkably close resemblance to the Nancy Drew pattern. None of the imitations, however, not even the Stratemeyer Syndicate’s own, proved as immediately popular as Nancy Drew, and none has ever rivaled her legendary grip on her audience. Nancy Drew not only outsold by far her competitors; she pushed most of them out of the marketplace within a few years of their appearance. The rare survivors never offered a serious challenge to Nancy’s position as reigning queen of the juvenile formula fiction world.

The basics of the Nancy Drew design are familiar. Nancy is an attractive sixteen-year-old girl who lives with her widowed, “famous lawyer” father, Carson Drew, and their “elderly housekeeper,” Hannah Gruen. It is a privileged existence of financial ease and extraordinary independence, which Nancy uses to pursue her calling as an amateur sleuth. Each story is a showcase for Nancy’s straight thinking, remarkable competence, and unshakable dignity, and every adventure ends with Nancy admired and applauded by all. Though she has friends — in particular her special “chums,” Bess and George, and an unemphatic boyfriend, Ned — Nancy essentially operates alone, doing most of the acting and all of the thinking in her detecting adventures. The series, too, is focused. A Nancy Drew mystery is only that, never a school story or a romance or a career novel with a bit of mystery thrown in.

Imitative authors saw the outlines of the pattern clearly enough: the one parent, two chums, one boyfriend, and comfortable middle-class girl sleuth soon became a standard figure in series fiction. Some authors stressed their heroines’ independence, as Adams did, and most supplied the admiration that surrounds Nancy Drew like a cloud of sweet scent. Yet all of them overlooked or weakened important parts of the formula. The autonomy that was Nancy’s without question, for example, and the single focus of the narratives were blurred in other series, though in retrospect, at least, both look like key elements in the Nancy Drew success.

In fact, the most moderate literary Darwinist would have to conclude that Nancy Drew’s capacity for survival came from sources never identified by would-be imitators. Even experienced hack writers like most of those who followed Adams into the girl detective field missed the magic, largely because they did not read the deeper messages in the books. They recognized the pieces but not the puzzle; they saw the surface without suspecting the undercurrent.

To examine these failed specimens is to come closer to understanding the essential ingredients in a recipe which could not, apparently, be altered very much without losing some of its peculiar charm. It is also a way of looking again at the underlying message in the Nancy Drew books — surely the most interesting mystery about them — since it is the message which says something about how and why they spoke to their readers so successfully.

Of the many Nancy Drew imitators, Kay Tracey came closest to reproducing exactly the obvious features of the original. This Stratemeyer series, written under the pseudonym Frances K. Judd, began in 1934 and ended eight years later. The protagonist, Kay, is sixteen, as Nancy was until the 1950s, with “beautiful brown eyes and light, waving hair . . . golden in the sun,” and “possessed of great energy and resourcefulness.” She has two devoted girl chums and a vague boyfriend named Ronald Earle. A slight variation on the model has Kay’s father dead and Kay living with her mother and Cousin Bill, a “rising young lawyer.”

The rigorously genteel diction is vintage Stratemeyer: “‘We have been objects of curiosity, if not of derision’” says Betty, one of the high school friends, who often “murmurs” her remarks. An acquaintance, who invites Kay to the opera, tells her that “‘Faust is being rendered,’” and Kay herself inquires of a police officer, whether a fire was “of incendiary origin.”

Some of the admirable simplicity of the Nancy Drew narratives has been lost, however, as well as Adams’s consistent emphasis on her sleuth’s rational detection methods. Kay Tracey plots make heavy demands on reader credulity, with coincidence and “hunches” accounting for most of Kay’s solutions — which often seem laboriously long in coming. In theory, at least, Nancy Drew proceeds along a different tack. It would be hard to argue that Nancy Drew narratives are, in fact, tightly woven or highly credible or that Nancy is really less dependent than Kay is on happy chance. Nevertheless, Adams tells her readers that Nancy works by logical reasoning from clues she has trained herself to see, even as others pass them by: “Nancy never guessed at anything." Except for her ability to discern criminality at a glance, Nancy’s prowess as a sleuth is, Adams insists, a matter of close observation and clear thinking. Not luck, but reason, according to Adams, is Nancy’s handmaiden.

When she isn’t lurching from coincidence to happenstance, Kay Tracey stands, like her model, in a constant shower of praise. The author tells us that Kay is “courageous,” “calm,” and “extremely popular”; that her voice has the “ring of authority”; and that she drives a car “skillfully through traffic.” So far, so good — but Nancy’s real advantages have slipped through the net.

The stories fail to support the kind of authority and autonomy that Nancy enjoys without question. The car is not Kay’s — it is Cousin Bill’s; the praise from other characters, especially male characters, is often thinned by condescension: “‘For a cousin, and a girl cousin at that,’” says the rising young lawyer, “‘you are unusually shrewd.’” Kay’s authority is also undercut by her clear identification as a schoolgirl. Though Nancy and Kay are the same age, Nancy is never connected with school; she carries no books, takes no exams. School is hardly a major consideration in Kay’s life, but it does crop up now and then, reminding the reader, however fleetingly, of the prosaic realities of high school existence, which rarely includes high adventure or an authoritative voice in the affairs of adults.

Changing the widowed parent from father to mother was also unwise. There is cachet as well as convenience in having a “prominent attorney” father, who admires even as he keeps out of the way, who offers strength and reassurance but at sufficient distance to insure that the limelight is always Nancy’s. Kay’s mother has no cachet at all, though she carries nonintervention to the point of idiocy. Hearing of Kay’s “exciting experience” of being hit over the head, drugged, and/or hypnotized at a Chinese estate, her mother’s reaction is outstandingly — and typically — flaccid: “‘I am afraid that I sometimes grant you too much freedom, Kay,’” she “declares” plaintively. “‘If anything should happen to you I’d never forgive myself.’” Yet even so spineless a mother as Mrs. Tracey occasionally draws the line: “‘Kay simply cannot miss another day of school,’” she finally “interposes,” and briefly, but distinctly, the reader hears again the thud of reality.

Realism, even if of a diluted quality, may also have demolished the Penny Nichols series — there were only four titles published between 1936 and 1939 — though it is what makes these stories rather engaging to an adult reader. Penny, the creation of Mildred A. Wirt (“Joan Clark”), has blue eyes, golden curls, no mother, a car, and a father who is a professional detective — all pretty familiar so far. But Penny’s “rattletrap roadster,” which she “paid for herself by teaching swimming at the YWCA,” breaks down often, keeping her chronically short of cash, a more likely condition for a 1930s teenager than Nancy’s enviable solvency. In fact, Wirt’s sense of reality tempers most of her borrowing from the Nancy Drew model. Though she says that Penny has “rare freedom” and “the complete confidence of her father,” neither Penny’s freedom nor her father’s confidence is quite so complete as Nancy Drew’s. Mr. Nichols often behaves like a real — albeit indulgent — father and sometimes like a real detective. He turns down Penny’s bid to be present while he interviews a member of a car theft ring, since the man “would never talk as freely” if she were there. When she proposes to hide in the closet to listen, he dismisses the idea “as a trifle too theatrical for my taste.” Nor does he talk to Penny about his cases, as Carson Drew does with Nancy; on the contrary he sometimes withholds information: “‘Not that I don’t trust you, but sometimes an unguarded word will destroy the work of weeks.’” As a matter of fact, “Penny knew that her father regarded her interest in the . . . case with amusement. He was humoring her in her desire to play at being a detective . . . he did not really believe that her contributions were of great value.”

More dampening still, Mr. Nichols challenges the notion that crooks “look like” crooks (“‘Appearances are often deceitful, Penny’”) or that Penny can be sure that someone isn’t the criminal type. “‘And just what is the criminal type? Give me a definition’” he asks exasperatingly, adding, in a most parental way, “‘I’m merely trying to teach you to think and not to arrive at conclusions through impulse or emotion.’” Alas, Nancy Drew’s success rate would have been cut in half had she not known “instinctively” who was and was not a crook.

Though Penny has some adventures, some of them quite like Nancy’s, others slightly more plausible, and though she reaps the familiar praise for her luck and information, reality impinges on her constantly. She isn’t always right, and she is firmly under adult authority. Unlike Hannah Gruen, the Nicholses’ “elderly housekeeper” feels free not only to scold Penny but to prevent her “investigating” a prowler outside the house. “You’ll do nothing of the kind. We’ll lock all the doors and not stir from the house until your father returns,” says she. And they do.

Adults do not turn to Penny for advice or help; her investigating efforts are viewed with tolerance at best and her achievements received with surprise. Her sleuthing is not invariably exciting. During a tedious wait for action, she sighs, “I don’t believe I’m cut out to be a lady detective”; to which her father replies with unglamorous accuracy, “A detective must learn to spend half of his time just waiting.” In short, everything about Penny Nichols — her possessions, talents, accomplishments, and experiences — are nearer human scale than are Nancy Drew’s, and especially nearer teenage human scale. Penny’s relationship with the adult world is perilously close to believable — no advantage in a genre whose central attraction is wish fulfillment.

Stratemeyer series are dependably long on wish fulfillment; it was not an overdose of realism that weakened the Dana Girls as rivals to Nancy Drew. These mysteries, another Stratemeyer product designed to capitalize on the Nancy Drew phenomenon, were also supervised by Harriet Adams under the Carolyn Keene pseudonym. The publishing history suggests reasonable profitability; the series began in 1934 and was still appearing in 1979, though at only half the rate of the Nancy Drews.

In spite of Adams’s guiding hand, the Dana Girls are but pallid followers in the dazzling train of Nancy Drew. Though the stories share, predictably enough, a number of features with their model, the focus in them has been diffused. Adams evidently wanted to combine the attractions of girl detective fiction with the boarding school story — a genre fading in popularity by the 1930s — but the result was more a compromise than a fresh triumph. The device of using two protagonists instead of one has some attractions. The usual chums are unnecessary, and it’s probably fun to think of having adventures with a congenial sister. On the other hand, sisters need to make more or less equal contributions to solving mysteries, where chums could be used to highlight the lone heroine’s superior qualities, as Bess and George set off Nancy’s. The Dana sisters cannot avoid sharing center stage; if Nancy does, it is through her own generosity — just another jewel in her crown.

As for the boarding school, no matter that it is “imposing,” amazingly undemanding, and infinitely accommodating about letting the sister sleuths out of class to pursue their mysteries, it is still a school. It gives exams, and for the sisters to be loosed for a day of vigorous detective work requires adult intervention. Their genial guardian, Uncle Ned (surely a major part of the wish fulfillment in these books), is always happy to plead their case, and they actually miss very little of whatever excitement there is. Nevertheless, the school’s presence weakens the mysteries, as the mysteries detract from the school story; the adult involvement takes some of the play away from the young protagonists, and the multiplicity of themes and characters blurs patterns that are sharply defined in the Nancy Drew books.

Lillian Garis’s Melody Lane mysteries, published by Grosset and Dunlap from 1933 to 1940, also feature sisters, Cecy and Carol, who have a car, a widowed father, and a housekeeper with minimal authority over them. Though these stories were not Syndicate produced, the odd-flavored class consciousness so common to Stratemeyer books is rampant here as well. A 1935 title describes a caretaker as “pleasant of face and manner yet sufficiently respectful to show . . . that he was a caretaker. He had the estate-retainer appearance and his little wife, who patted along back of him, seemed anxious to please.” The xenophobia is also familiar, with swarthiness and foreign used as pejorative terms. Cecy refers to “‘queer dark women,’” remarking that she “‘never did like these foreign beauties.’”

About here, however, close parallels between Garis’s series and Nancy Drew ends. Compared with any Stratemeyer book, Garis’s are wordy and slow-paced; action waits upon aimless conversations and inconsequential business. The defect is surprising since Lillian Garis had written for Stratemeyer and ought to have understood the primacy of fast action in the Syndicate successes. Melody Lane plots are — by series standards — complex, with many secondary characters whose motivation is often unclear. Diction is quite unlike that of most Stratemeyer stories and especially unlike the Nancy Drews. While adults speak with reasonable formality, young characters, including Cecy, use slang freely: swell, bucks, kid, and dead ringer. Amongst themselves, the girls chatter constantly about clothes and “cute boys.”

But the most fundamental difference between Garis’s girls and Nancy Drew is their distinctly secondary role vis-à-vis males, whether men or boys. Girls meet disparagement on every hand, from their own sex as often as from males. “‘Mere females should keep out of the way of vast machines’”; “‘Girls always have so many little things on their minds they just might neglect the real big ones’”; and “‘silly girl stunts’” are all typical remarks — and two of the three are out of the mouths of females. Girls scream and dither in tense situations, while boys act “calmly, as boys always do in an emergency,” and men solve problems that baffle women and girls. Small wonder that somebody in a Garis book is forever exclaiming that “it was such a relief to have a man there.”

The plot action, such as it is, reinforces the idea that girls are inept, reactors rather than initiators. Cecy and Carol are sometimes brave, sometimes not, but nearly always they respond to situations rather than undertaking action — a very non-Nancy Drew approach. Nowhere in Garis’s series is there the continuous tribute to her heroines’ competence, courage, style, and renown that can be found in every chapter of every Nancy Drew mystery. And indeed, frivolous, small-minded, and dependent as they are, these girls have little claim on such paeans as Nancy earns on all sides at all times.

On the other hand, the author of the Dorothy Dixon mysteries surely went too far in the opposite direction. This series — written by “Dorothy Wayne” (pseudonym for Noel E. Sainsbury) and published by the Goldsmith Publishing Company — lived and died, like a mayfly, in a single season; all four titles came out in 1933. The books are a startling departure from other would-be Nancy Drew duplicates. If the Melody Lane sisters are less carefully genteel than Nancy Drew, Dorothy Dixon is in another league altogether. Dorothy — a sixteen-year-old “fly-girl” who owns a plane, knows jujitsu, throws a knife with deadly accuracy, and frequently carries a gun — operates at the far edge of seemliness for a girl of her era. Brusque, sarcastic, and aggressive, she bosses her “feminine” friend, Betty — whom she refers to as a “fluffball” — unmercifully. Like Nancy, Dorothy is famous for solving mysteries (“nice ladylike reputation, what?”), but her temper is uneven and her language relentlessly tough and slangy.

Improbable as it may seem, Dorothy has a boyfriend who collaborates on some adventures, though without calling forth much maidenly gratitude from Dorothy. Once, on a desperate climb up a rocky cliff in the dark, friend Bill points out that most of Dorothy’s skirt has been torn away. “‘What of it?’” replies Dorothy, with her usual grace, “There’s a perfectly good pair of bloomers underneath.” Edward Stratemeyer would have fainted dead away.

In the staid company of the 1930s series books, the Dorothy Dixons stand out as bizarre indeed. One cannot imagine Nancy being propositioned by a young gangster, as Dorothy is, and the mind lulled by Stratemeyer propriety boggles at Dorothy’s laughing reply that she is “expensive.” Capping even this remarkable exchange is the wrestling match between the gangster and Dorothy — which she, of course, wins.

Over all, these books are so far from the hackneyed, imitative safety of most series stereotypes of girls that I have speculated whether Mr. Sainsbury felt a sociologist’s curiosity about the audience for girl sleuth tales. Certainly, he never made his heroine play second fiddle to male dominance. As Bill so truly says to his lady love, “‘It’s your show.’” “‘Attaboy!’” says Dorothy.

But the Dorothy Dixon mysteries — which are quite awful, however liberated — overreached the mark or overstrained reader credulity, probably both. Perhaps Nancy Drew fans could believe in a roadster but not a plane; more likely, they recognized that a Dorothy Dixon brash self-assertion went well beyond anything their own society was prepared to tolerate in girls, so they could neither believe nor embrace this thorny model, even wishfully. Even as fantasy, the Dorothy Dixon series was well outside the pale.

Evidence that the world was not yet ready for Dorothy Dixon might be found in the Judy Bolton series by Margaret Sutton, which began in 1932 and lasted until 1967. Fly-girl Dorothy, who had a “long arm . . . unbending as tempered steel,” had a will and ego to match. Judy, on the other hand, though billed as the solver of the mysteries published in her name, is prey to every standard feminine weakness; no one could mistake her for a feminist outpost.

In fairness, these books shouldn’t be judged primarily as imitations of the Nancy Drew pattern, although Judy’s sleuthing was an important part of every story. Sutton filled out the usually spare series formulas with more complex characters, as well as moving her main character along life’s road from high school girl to young married woman. The earliest books were as much school stories as detective yarns, and soon, as Judy’s acquaintance with Peter Dobbs developed, they became romances — of a very tame sort — as much as mysteries.

Except for the first few books, Judy is older than most of the girl sleuths who emulated Nancy Drew, and her age, if not her temperament, confers the requisite independence. Judy, however, squanders her independence on Peter, even taking typing and shorthand so that she may help him in his office, “acting as his secretary, she proudly told friends.”

From the mildest feminist point of view, the Judy Bolton stories are discouraging, though certainly typical of their period. Judy is jealous, unreasonable, and dependent. It is impossible to imagine Nancy Drew confessing that she is “afraid of thunder” and “snuggling a little closer to [anybody] as he drove the car,” or sobbing on Ned’s shoulder as Judy sobs on Peter’s when he comes to the “haunted” house of strange noises. One must assume that the appeal of these books was largely that of a conventional “girl’s story,” with family, school, and romance formulas heightened a little with mystery. It is not surprising that Sutton’s book-a-year contract with Grosset and Dunlap was canceled in 1967.

Nancy Drew’s success eluded every one of her rivals. Even those that survived past the 1930s never approached the Nancy Drew sales and certainly never wrote themselves on youthful hearts as Nancy did. Something in the Nancy Drew stories set them apart from others of the genre, making them deeply satisfying, not just to the generation of girls who read them first but to millions of girls who came after and who read them with the same passionate absorption in a very different cultural climate. The non-Nancy Drew girl detective stories go a long way toward clarifying what that special something was.

From the May/June 1987 issue of The Horn Book Magazine. The second part of this article appeared in the July/August 1987 Horn Book; read it here.

RELATED

RECOMMENDED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!