2018 School Spending Survey Report

What Makes a Good Middle-Grade Memoir?

Memoir is a genre that often gets subsumed under the big banner of biography.

A good example of a different sort of life is A Gift from Childhood: Memories of an African Boyhood, written by artist Baba Wagué Diakité about growing up in rural Mali. Stories about friendship, chores, moving to a new home, and becoming a man through “washing hands” (i.e., circumcision) are all conveyed in brief chapters. Illustrations on painted and fired earthenware tiles accompany these vignettes, and folded within Diakité’s own anecdotes are the fables he heard as a boy. This dual narrative not only tells about one person’s particular circumstances but also brings readers into the oral storytelling tradition of Mali. And the genie of Mali will be a memorable new addition to the cast of folktale characters middle-grade readers already know.

A good example of a different sort of life is A Gift from Childhood: Memories of an African Boyhood, written by artist Baba Wagué Diakité about growing up in rural Mali. Stories about friendship, chores, moving to a new home, and becoming a man through “washing hands” (i.e., circumcision) are all conveyed in brief chapters. Illustrations on painted and fired earthenware tiles accompany these vignettes, and folded within Diakité’s own anecdotes are the fables he heard as a boy. This dual narrative not only tells about one person’s particular circumstances but also brings readers into the oral storytelling tradition of Mali. And the genie of Mali will be a memorable new addition to the cast of folktale characters middle-grade readers already know. Quang Nhoung Huynh’s Water Buffalo Days: Growing Up in Vietnam describes experiences (catching fish to sell at market, organizing cricket fights, harvesting crops) and a setting (the Vietnam hills and jungles before the devastation of the Vietnam War) that will be unfamiliar to most contemporary readers. Family members and beloved pets appear in short episodic chapters that encapsulate one young person’s defining moments. In “Naming the Bull,” for example, the clash between two water buffalo bulls, prized animals of village families, can be seen as an allegory about strength and conflict. The battle ends when the older creature rams its head into an earthen bank. In a rage it rips its own horns off in the ground. Its resultant death and the reactions of the families offer subtle messages left for the readers to discern. Huynh opens his book with an introduction that draws a stark line between past and present, making the stories all the more poignant: “War disrupted my dreams. The land I love was lost to me forever. These are my memories.”

Quang Nhoung Huynh’s Water Buffalo Days: Growing Up in Vietnam describes experiences (catching fish to sell at market, organizing cricket fights, harvesting crops) and a setting (the Vietnam hills and jungles before the devastation of the Vietnam War) that will be unfamiliar to most contemporary readers. Family members and beloved pets appear in short episodic chapters that encapsulate one young person’s defining moments. In “Naming the Bull,” for example, the clash between two water buffalo bulls, prized animals of village families, can be seen as an allegory about strength and conflict. The battle ends when the older creature rams its head into an earthen bank. In a rage it rips its own horns off in the ground. Its resultant death and the reactions of the families offer subtle messages left for the readers to discern. Huynh opens his book with an introduction that draws a stark line between past and present, making the stories all the more poignant: “War disrupted my dreams. The land I love was lost to me forever. These are my memories.” An African American grandmother, mother, and daughter share their memories in Childtimes: A Three-Generation Memoir by Eloise Greenfield and Lessie Jones Little. Pattie Frances Ridley Jones, born in 1884, is the first voice that readers encounter: “It’s been a good long time since my childtime. Yours is now, you’re living your childtime right this minute, but I’ve got to go way, way back to remember mine.” This long-ago time in American history includes snapshots of daily life that will seem familiar to contemporary middle graders (memories of the family congregating in the kitchen at the end of a long day, for example); many more stand in sharp contrast to modern life (no running water, handmade clothes, one-room schoolhouse). Readers experience the accumulated joys and sorrows of one family’s history: the death of siblings, weddings, bigotry, Northern migration, school segregation, etc. Illustrations by Jerry Pinkney, along with period photographs, enhance the stories’ emotional and historical relevance for middle graders.

An African American grandmother, mother, and daughter share their memories in Childtimes: A Three-Generation Memoir by Eloise Greenfield and Lessie Jones Little. Pattie Frances Ridley Jones, born in 1884, is the first voice that readers encounter: “It’s been a good long time since my childtime. Yours is now, you’re living your childtime right this minute, but I’ve got to go way, way back to remember mine.” This long-ago time in American history includes snapshots of daily life that will seem familiar to contemporary middle graders (memories of the family congregating in the kitchen at the end of a long day, for example); many more stand in sharp contrast to modern life (no running water, handmade clothes, one-room schoolhouse). Readers experience the accumulated joys and sorrows of one family’s history: the death of siblings, weddings, bigotry, Northern migration, school segregation, etc. Illustrations by Jerry Pinkney, along with period photographs, enhance the stories’ emotional and historical relevance for middle graders. Nonfiction for youth often mines the past for perspectives on history from a kid’s-eye view, and memoirs can offer a direct emotional perspective of people who lived history when young. As the Cultural Revolution begins to grip China, Ji-li Jiang sensed a shift: “I achieved and grew every day until that fateful year, 1966. That year I was twelve years old, in sixth grade.” Red Scarf Girl: A Memoir of the Cultural Revolution opens at the beginning of a social upheaval that topples young Jiang’s future plans. Her thespian family, living in a large home, is looked upon with suspicion. Young people are rallied to battle the “Four Olds” (culture, customs, ideas, habits), which on one occasion requires Jiang to publically humiliate her aunt. Jiang begins to feel like life is becoming less hopeful and promising. “The future had been full of infinite possibilities. Now I was no longer sure that was still true.” The frustration of being forced to do things an adult says is a familiar experience of the middle years, here writ large.

Nonfiction for youth often mines the past for perspectives on history from a kid’s-eye view, and memoirs can offer a direct emotional perspective of people who lived history when young. As the Cultural Revolution begins to grip China, Ji-li Jiang sensed a shift: “I achieved and grew every day until that fateful year, 1966. That year I was twelve years old, in sixth grade.” Red Scarf Girl: A Memoir of the Cultural Revolution opens at the beginning of a social upheaval that topples young Jiang’s future plans. Her thespian family, living in a large home, is looked upon with suspicion. Young people are rallied to battle the “Four Olds” (culture, customs, ideas, habits), which on one occasion requires Jiang to publically humiliate her aunt. Jiang begins to feel like life is becoming less hopeful and promising. “The future had been full of infinite possibilities. Now I was no longer sure that was still true.” The frustration of being forced to do things an adult says is a familiar experience of the middle years, here writ large. The Boy on the Wooden Box: How the Impossible Became Possible…on Schindler’s List revisits a terrible and well-documented time through the eyes of a middle grader. When in December 1939 the Nazis announced that Jews could no longer attend school in Kraków, narrator Leon Leyson is happy at first about not having to go: “What ten-year-old wouldn’t enjoy a few days off from school?” This real and genuine child reaction makes him believable to middle-grade readers even as it shows the sharp contrast to the harsh reality evolving around him; for example, on the night when his father is beaten and removed from their apartment. As he remembers, “Until that evening I had thought I had a special immunity, that somehow the violence wouldn’t touch me.” Violence and injustice caused his childhood to come to an abrupt end, but child readers will stick with his story: Leyson’s resilience in the face of hardship will embolden middle graders to face their own struggles.

The Boy on the Wooden Box: How the Impossible Became Possible…on Schindler’s List revisits a terrible and well-documented time through the eyes of a middle grader. When in December 1939 the Nazis announced that Jews could no longer attend school in Kraków, narrator Leon Leyson is happy at first about not having to go: “What ten-year-old wouldn’t enjoy a few days off from school?” This real and genuine child reaction makes him believable to middle-grade readers even as it shows the sharp contrast to the harsh reality evolving around him; for example, on the night when his father is beaten and removed from their apartment. As he remembers, “Until that evening I had thought I had a special immunity, that somehow the violence wouldn’t touch me.” Violence and injustice caused his childhood to come to an abrupt end, but child readers will stick with his story: Leyson’s resilience in the face of hardship will embolden middle graders to face their own struggles. As the saying goes, a picture can be worth a thousand words, and a good illustrated memoir can help readers visualize complex ideas, see the cause and effect of actions, and empathize with others. The Wall: Growing Up Behind the Iron Curtain shows the isolation, fear, and contrasts of life in Communist-ruled Czechoslovakia. Composed mostly with black ink, Peter Sís’s illustrations convey his younger self’s drab existence — until his life becomes enlivened by the psychedelic colors of the Beatles, whom Sís hears as a call to freedom. On the wings of his dreams — and music — the young boy flies out of the confining mental space of the regime.

As the saying goes, a picture can be worth a thousand words, and a good illustrated memoir can help readers visualize complex ideas, see the cause and effect of actions, and empathize with others. The Wall: Growing Up Behind the Iron Curtain shows the isolation, fear, and contrasts of life in Communist-ruled Czechoslovakia. Composed mostly with black ink, Peter Sís’s illustrations convey his younger self’s drab existence — until his life becomes enlivened by the psychedelic colors of the Beatles, whom Sís hears as a call to freedom. On the wings of his dreams — and music — the young boy flies out of the confining mental space of the regime. The design and formatting of Chuck Close: Face Book embraces the artistic expression of Close and invites readers to investigate the images of his life story. The book is made up of interview questions, asked by fifth graders who visited Close’s studio, and the artist’s answers. In the middle of the book, several self-portraits are printed on heavy-weighted paper cut into thirds, giving readers the opportunity to mix and match Close’s self-representation across time. This playful reconfiguring reveals the artist while inviting questions about why he has created so many self-portraits, the reasons behind his chosen media, and his consistent use of the grid pattern. His recollections are spurred forward by the students’ inquiring minds, and Close answers honestly about illness, mistakes, influences, and the multifaceted creative process.

The design and formatting of Chuck Close: Face Book embraces the artistic expression of Close and invites readers to investigate the images of his life story. The book is made up of interview questions, asked by fifth graders who visited Close’s studio, and the artist’s answers. In the middle of the book, several self-portraits are printed on heavy-weighted paper cut into thirds, giving readers the opportunity to mix and match Close’s self-representation across time. This playful reconfiguring reveals the artist while inviting questions about why he has created so many self-portraits, the reasons behind his chosen media, and his consistent use of the grid pattern. His recollections are spurred forward by the students’ inquiring minds, and Close answers honestly about illness, mistakes, influences, and the multifaceted creative process. A good memoir won’t get bogged down in the moral of the storytelling — the life lessons will come through without pedantry. Humor is the vehicle many memoirists use. Stories about six brothers and their school principal father are sure to contain some wisdom and plenty of laughs (along with broken bones, practical jokes, and barfing). Knucklehead: Tall Tales & Mostly True Stories About Growing Up Scieszka describes the trials and tribulations of a pack of boys — including the book’s author Jon Scieszka, the second-oldest of the bunch — sharing Halloween costumes, building models, and attending mandatory piano lessons. The relatability of these experiences for readers lends credibility to the teller, as do illustrations from the time period, photographs of his family, and other artifacts of the time (such as the report card from the year Scieszka got a C in religion). Readers reluctant to use the tools of nonfiction texts will happily pore over the index with entries reading like urban legend (“hobo — mad with machete, 72”).

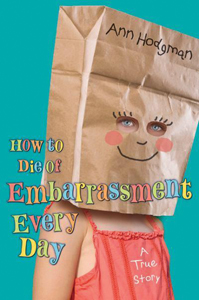

A good memoir won’t get bogged down in the moral of the storytelling — the life lessons will come through without pedantry. Humor is the vehicle many memoirists use. Stories about six brothers and their school principal father are sure to contain some wisdom and plenty of laughs (along with broken bones, practical jokes, and barfing). Knucklehead: Tall Tales & Mostly True Stories About Growing Up Scieszka describes the trials and tribulations of a pack of boys — including the book’s author Jon Scieszka, the second-oldest of the bunch — sharing Halloween costumes, building models, and attending mandatory piano lessons. The relatability of these experiences for readers lends credibility to the teller, as do illustrations from the time period, photographs of his family, and other artifacts of the time (such as the report card from the year Scieszka got a C in religion). Readers reluctant to use the tools of nonfiction texts will happily pore over the index with entries reading like urban legend (“hobo — mad with machete, 72”). How to Die of Embarrassment Every Day by Ann Hodgman also zips along using a steady fuel of humor and self-deprecation. Familiar scenes of middle-grade life abound — including going to birthday parties (and all the attendant anxiety), pestering your parents for a pet, choosing names for your future children, worrying that your nose is too big, and accidentally destroying private property (and blaming others for it). Hodgman lets readers decide how they might act in the situation. Take her own actions as exemplary or not.

How to Die of Embarrassment Every Day by Ann Hodgman also zips along using a steady fuel of humor and self-deprecation. Familiar scenes of middle-grade life abound — including going to birthday parties (and all the attendant anxiety), pestering your parents for a pet, choosing names for your future children, worrying that your nose is too big, and accidentally destroying private property (and blaming others for it). Hodgman lets readers decide how they might act in the situation. Take her own actions as exemplary or not.Amidst all the hilarity, both Scieszka and Hodgman make a point of mentioning the importance of books during their childhood. In sharing the stories that mattered to them, they alert readers to particular titles and authors while also giving insight into how reading can shape us. In a chapter about the relative wealth of different generations, Hodgman comments on the lack of stuff — including snack food — in the Henry Huggins books (“Once Beezus had a cabbage core as a snack. A cabbage core! My tortoises won’t even eat cabbage!”). And Scieszka recalls fondly the time he spent reading the Golden Book Encyclopedia set owned by his family. “I was amazed that so much information could be packed into a picture. It was like reading without reading.”

History can be told in large sweeping narratives of great and powerful persons. It can also be told through the eyes of young people who are inheriting the changing world. Good memoirs that incorporate middle-grade perspectives can help readers see their own position in the world, to understand that they, too, live in an historical context, that their actions affect other people and that their choices will influence who they are as adults. Memoirs let them know they have something valuable to say and their experiences deserve to be communicated.

Good Middle-Grade Memoirs

Chuck Close: Face Book (Abrams, 2012) by Chuck Close

A Gift from Childhood: Memories of an African Boyhood (Groundwood, 2010) by Baba Wagué Diakité

Childtimes: A Three-Generation Memoir (Crowell, 1979) by Eloise Greenfield and Lessie Jones Little; illus. by Jerry Pinkney

How to Die of Embarrassment Every Day (Holt, 2011) by Ann Hodgman

Water Buffalo Days: Growing Up in Vietnam (HarperCollins, 1997) by Quang Nhuong Huynh; illus. by Jean Tseng and Mou-sien Tseng

Red Scarf Girl: A Memoir of the Cultural Revolution (HarperCollins, 1997) by Ji-li Jiang

The Boy on the Wooden Box: How the Impossible Became Possible…on Schindler’s List (Atheneum, 2013) by Leon Leyson with Marilyn J. Harran and Elisabeth B. Leyson

Knucklehead: Tall Tales & Mostly True Stories About Growing Up Scieszka (Viking, 2008) by Jon Scieszka

The Wall: Growing Up Behind the Iron Curtain (Foster/Farrar, 2007) by Peter Sís

From the September/October 2014 issue of The Horn Book Magazine.

RELATED

RECOMMENDED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!