2018 School Spending Survey Report

Krik, Krik, Krik: How Aardema & Co. Attuned Us to African Folklore

Richard Dorson, the late dean of American folklorists, had a word for folklore that was not authentic, not the voice of the people.

Dorson and other folklorists didn’t concern themselves with “Cinderella” and the like, stories that had long since passed from oral into written literature. So when the picture-book explosion of the 1960s and 1970s swept up classic fairy tales and popular favorites of the “Tom Tit Tot” variety, they didn’t blink; it was librarians and others of a literary bent who recoiled at the subordination of words to pictures, and sometimes still do.

The search was also on for new material, however, and at a time of Third World consciousness it extended far beyond Europe. Authors and illustrators took a new interest in African tales — little known for the most part and often intriguingly different: stories of the beginnings of things, how-and-why tales, trickster yarns in the Brer Rabbit vein. Characteristically down-to-earth and wildly fanciful, they had potential child appeal in plenty.

Illustrating them called for — and rewarded — a creative leap. Tackling an African trickster tale, The Coconut Thieves (1964), prepared Janina Domanska for her semi-abstract masterwork If All the Seas Were One Sea; Blair Lent, adept at tailoring form and style to culture, turned Elphinstone Dayrell’s Why the Sun and Moon Live in the Sky (1968) into a crafty, suspenseful reenactment. Imagine the water and his people, urged to visit, filling the house of the sun and his wife the moon until the sun and the moon rise to the roof . . . Still, these estimable, low-key books remained a tad alien, outside the American mainstream. They lacked visual impact at a distance too, which limited their use in Head Start programs and other increasingly important group settings. They intrigued; they didn’t quite connect.

The career of one snappy midwestern woman — a confluence of social, economic, and artistic forces — brought an end to all that.

Verna Aardema, whose twenty picture books introduced African folklore to millions of American children, spent most of her life in the small, predominantly Dutch city of Muskegon, Michigan — raising her two children, teaching school, reading about distant places, and writing for the local paper.

Not so fast, though. To induce her daughter, a picky eater, to finish her meals, Aardema made up stories of African life to tell her — “feeding stories,” as she called them — and submitted one to Instructor magazine. When it was published, she sent a copy to a children’s book editor, who suggested she treat it as the first chapter of a book. Aardema proposed instead a collection of African stories adapted for children; she’d been telling them to her second graders for years, and holding them spellbound. In a school without African American children, in the heyday of Dick and Jane, that very experience was the heart of the matter. Tales from the Story Hat made a timely appearance in 1960, just about when the interest in new African nations was morphing into an interest in African American origins. It was also dressed for success with illustrations by the African American artist Elton Fax, who had recently been in Africa, and an enthusiastic introduction — as good as an imprimatur — by Augusta Baker, the eminent African American head of children’s services at the New York Public Library.

One could say that Tales from the Story Hat was fitted out for success, as well, in the image of the “story hat” — a wide-brimmed hat worn by a West African storyteller, as Aardema explains, with carvings dangling from its brim: “Whoever asks for a story picks an object...” The stories in the book, she continues, are like those of the storyteller “who carries his stories in his head and the Table of Contents on his hat.” Did Aardema herself wear a storytelling hat in the classroom? Or did she capture the children’s imagination, as she does the reader’s, with the mere figurative image?

Soon she didn’t need props, imaginary or real. Aardema started with little more than an interest in Africa, quite possibly stimulated by her church’s missionary efforts, which set her to reading about African life and exploring African folklore. At the time Baker attested to her expertise, that was about where she was. But Aardema learned what was expected of a scholar, in the way of sources and source notes, and with her usual zest she grew into the role. Out went stories adapted from Henry Morton Stanley and other celebrated travelers, in went tales recorded by ethnographers and other specialists that two local librarians, whom she thanks, “combed libraries in four states” to find for her.

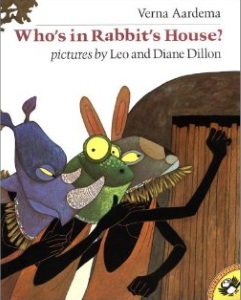

Two more well-received collections followed, along with three brief stories in easy-reader form (prompted by the popularity of The Cat in the Hat). Aardema acquired — or was acquired by — the leading children’s book agent of the time, Marilyn Marlow. And along with a new editor and publisher, Phyllis Fogelman at Dial, Aardema’s next collection got a dramatic new look, thanks to the combined talents of art director Atha Tehon and illustrators Leo and Diane Dillon, already known for the arresting design and technical finesse of their wide-ranging work.

By instinct and by accident, a little history was about to be made. When Aardema submitted her next collection of stories, Fogelman asked to pull one out and publish it as a picture book, if the Dillons — whose one previous picture book had been, significantly, the interpretation of a Native American legend — would take it on. Why Mosquitoes Buzz in People’s Ears, published in 1975, brought instant renown to author and illustrators, and handily won the Caldecott. The color is luscious; the filmy air-brushed surfaces are seductive; the composition, in the abstract, is striking. But to my mind the events of the story are obscured, rather than illuminated, by the complex, monumental pictures — a pile-up of motifs clamoring for attention. Except — KPAO! — for the last page.

By instinct and by accident, a little history was about to be made. When Aardema submitted her next collection of stories, Fogelman asked to pull one out and publish it as a picture book, if the Dillons — whose one previous picture book had been, significantly, the interpretation of a Native American legend — would take it on. Why Mosquitoes Buzz in People’s Ears, published in 1975, brought instant renown to author and illustrators, and handily won the Caldecott. The color is luscious; the filmy air-brushed surfaces are seductive; the composition, in the abstract, is striking. But to my mind the events of the story are obscured, rather than illuminated, by the complex, monumental pictures — a pile-up of motifs clamoring for attention. Except — KPAO! — for the last page.If Aardema’s narrative nonetheless holds its own, that’s at least partly because she discovered African ideophones — in Richard Dorson’s African Folklore, proffered by a helpful librarian — just in time to insert a dozen strategically into the text, starting with wasu wusu for the python. And they registered: when I proposed writing about Aardema to Roger Sutton, children’s librarian emeritus, he e-mailed back: “right — krik, krik, krik — Aardema — swish, swish, swish.”

Aardema the classroom storyteller was a picture-book natural. Reading a picture book aloud — with due attention to rhythm, pacing, inflection — is akin to a performance. In front of a group, it is a performance. African folktales, like most of the world’s oral literature, are also, in a sense, picture-book ready. For one thing, they’re customarily performed in situ, with gestures and audience participation; for another, the narrator is free to improvise — “to bind together the various episodes, motifs, characters, and forms at his disposal,” as the Africanist Ruth Finnegan has written, “into his own unique creation, suited to the audience, the occasion, or the whim of the moment.”

Aardema probably didn’t read Finnegan, and she had no need to: she didn’t know otherwise. To infect her students with her own enthusiasm for African stories, she adapted them freely. In writing picture books, with their special needs, she did more than adapt the stories — she pretty much remade them.

Who’s in Rabbit’s House? (1977), the second Aardema-Dillon picture book, is a tour de force of writing and illustration — animated, witty, and exuberantly expressive. The story: Rabbit returns to her house one day and finds it occupied by an interloper with a big, bad voice. “I am the The Long One,” it roars. “I eat trees and trample on elephants. Go away! Or I will trample on you!” Rabbit dismisses Frog’s offer of help — "You are so small. You think you could do what I cannot?”— and finds that Jackal and Leopard and Elephant are no help at all: to get the interloper out, they would destroy the house. Then Frog renews her offer, and making her voice loud, thunders, “WHO’S IN RABBIT’S HOUSE?” Shortly, out comes a terrified, trembling caterpillar, to the merriment of Rabbit and the others duped.

Who’s in Rabbit’s House? (1977), the second Aardema-Dillon picture book, is a tour de force of writing and illustration — animated, witty, and exuberantly expressive. The story: Rabbit returns to her house one day and finds it occupied by an interloper with a big, bad voice. “I am the The Long One,” it roars. “I eat trees and trample on elephants. Go away! Or I will trample on you!” Rabbit dismisses Frog’s offer of help — "You are so small. You think you could do what I cannot?”— and finds that Jackal and Leopard and Elephant are no help at all: to get the interloper out, they would destroy the house. Then Frog renews her offer, and making her voice loud, thunders, “WHO’S IN RABBIT’S HOUSE?” Shortly, out comes a terrified, trembling caterpillar, to the merriment of Rabbit and the others duped.Frog, of course, has the biggest laugh of all.

Aardema had turned the story into a play for her second graders to perform each year for their parents, and the Dillons depict it in toto as a performance — with masked humans, the Masai villagers, playing animals. Occasionally the unorthodox staging produces confusion; more often, the onlooker looks harder and sees more.

"Who’s in Rabbit’s House?” originally appeared in The Masai, Their Language and Folklore (1905), by Sir Claud Hollis, under the title “The Story of the Caterpillar and the Wild Animals.” In the original story, accordingly, there’s no mystery about who’s in the rabbit’s house; the caterpillar goes in at the outset, while the rabbit is away. Then, yes, he bamboozles the rabbit and the other animals until the frog coolly turns the tables on him. Aardema first retold the story in her 1969 collection, Tales for the Third Ear, and besides inverting the core situation to make the audience as ignorant of The Long One’s identity as the animals are, she develops each animal’s approach to the problem into a separate, detailed incident. Not until the picture-book version, however, does the frog take a focal, before-and-after role as the small, slighted animal who proves his — or her — mettle.

Aardema knew what she was doing, and told others. For distribution at public appearances, she had a set of directives titled “How to Tailor African Folktales to Fit American Children.” Some are basic rules for writing children’s stories (“eliminate unnecessary characters,” “round out the ending”); some have particular application to the rewriting of folktales (“fix the opening formula,” “let each episode give promise of a solution”); and some reflect more immediate and specific concerns. With no sign of discomfiture, Aardema advises adapters to find stories “close to the African soil” and, at the same time, to “eliminate ugly details and unnecessary violence.” You may have noticed that in Who’s in Rabbit’s House? both Rabbit and Frog are female; they changed sex, as it were, for the picture-book text. Rule number four: “Create a sexual balance among the characters.” Authenticity, in short, doesn’t figure in at all.

Should it? Are the changes distortive, or reinforcing? The story now has suspense, in addition to serial deception; it has true supporting roles for Rabbit’s animal pals; it has a personable representative of brain-over-brawn in Frog; and it has a mixed cast that long-held custom denied it. In a roundabout way, the story Sir Claud Hollis collected as an ethnographic specimen is more fully realized, for all comers, in its latter-day, full-dress performance. It has returned to Africa in its new form too, along with other Aardema stories, and in native languages as well as in English — part of the centuries-old cultural exchange that of late has only grown more pervasive and complex.

Bringing the Rain to Kapiti Plain, the most beguiling of all Aardema’s books, probably has the most problematic backstory. The charm is inseparable from the illustrations by Beatriz Vidal, a newcomer of gentle mien and keen grasp, and so are the major alterations.

Bringing the Rain to Kapiti Plain, the most beguiling of all Aardema’s books, probably has the most problematic backstory. The charm is inseparable from the illustrations by Beatriz Vidal, a newcomer of gentle mien and keen grasp, and so are the major alterations.For years, Aardema relates, “The Nandi House That Jack Built” lay dormant in her notebook, ruled out by references to goat’s dung, a slaughtered cow, and head lice as factors in a rhythmic, cumulative tale that begins with an effort to bring rain to the parched plain: “Who will cast dung at me?” the narrator starts off, asking for salvation — which might have been cited, in 1999, in defense of Chris Ofili’s dung-spattered painting of the Virgin Mary, a cause célèbre when it was exhibited at the Brooklyn Museum. Then, as it happens, Aardema re-encountered the original rhymed “House That Jack Built.” She extracted the burnt grass, the eagle’s feather, and the wife and child from the Nandi story and, by a large stretch of the imagination, produced Bringing the Rain to Kapiti Plain, wherein the Nandi herdsman Ki-pat uses the eagle’s feather to shoot a rain cloud (“A feather that helped / to change the weather”) rather than to slaughter the enemies’ oxen to obtain a wife and child. As folklore, Bringing the Rain to Kapiti Plain is inescapably a fraud; Dorson would have called it fakelore for sure. But anyone who remembers James Earl Jones’s rendering in the “Reading Rainbow” presentation is not likely to grumble.

For the purposes of the picture book, another adjustment of the text was called for. “One day,” Aardema writes, “my editor [Phyllis Fogelman] called me and said, ‘Beatriz Vidal is in the office with the book dummy. . . It is going to be beautiful. But the first twopage spread shows the black cloud and the brown grass, and it is not a good beginning. Can you write an introduction that will show the plain in all its glory for the first two-page spread? And for the second, describe the drought?’” Aardema’s revision makes for a more dramatic opening of the book, too, moving from “fresh and green” to the rains “so very belated,” a phrase that alone raises the rhymed text from near-doggerel to semi-ballad status.

The pictures are unmistakably pastoral, a word that in itself implies breadth and calm. Vidal had studied with Ilonka Karasz, whose sophisticated transpositions of European peasant art graced both New Yorker covers and children’s books in the 1940s. The foreground grasses, turning from shades of brown to shades of green spike by spike, are easily the book’s most important single motif; when the rain finally falls, the grasses soak it up, along with the cows, and signal their deliverance.

Imaginative illustration may alter a story; like revisions of the text, it may also enhance and extend it.

The twenty Aardema stories of African origin made into picture books up to her death, in 2000, were illustrated by fifteen different artists, almost none of them specialists in folklore or Africana; in virtually every instance, regardless, the illustrations were praised as somehow African. If work by Marc Brown, Jerry Pinkney, Victoria Chess, Susan Meddaugh, Will Hillenbrand, and Joe Cepeda, along with the Dillons and Beatriz Vidal, can all be taken as African, the image of a monolithic Africa is, happily, kaput. Aardema lit upon juicy stories, in a variety of forms, from a number of tribal cultures. In her hands, they didn’t sound alike, and with a judicious selection of illustrators by Atha Tehon and other art directors, they didn’t look alike. Heterogeneous and vigorously alive, Aardema’s improbable body of work was absorbed into the omni-American experience.

From the November/December 2006 issue of The Horn Book Magazine.

RELATED

RECOMMENDED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!