2018 School Spending Survey Report

Kids' Own Publishing

In 2014 co-founder and publisher Victoria Ryle held a party in Melbourne, Australia, to celebrate Kids’ Own Publishing’s 100th book.

As a young teacher in North London in the 1980s, Ryle attempted to find out why a young Gujarati boy in her class was unable to read a book that had only one word: mummy. When she talked with him about it, he pointed to the middle-class white woman pictured and said, “That’s not my mummy.” Inspired by this experience and aided by her printmaker husband, Simon Spain, Ryle began to make books with her students using their own stories.

Then in 1997 she founded Kids’ Own Publishing Partnership in Ireland, using the model of artist-led bookmaking. Among their early publications was Can’t Lose Cant, the first known book for children featuring Cant, the language of the Irish Traveller community. (Kids’ Own Publishing Partnership in Ireland continues to this day under different leadership.)

When her family relocated to Melbourne in 2003, Ryle worked, at first on her own, refining the not-for-profit, artist-led publishing model to develop Australia’s Kids’ Own Publishing. Ryle partnered with government and community agencies, making books with families in playgroups, libraries, and schools.

How does it work? Professional artists — sculptors, collage- and printmakers, puppeteers — get together with children and families. Making art together stimulates talk, and out of this talk comes the text for a book. The children are not specifically directed to make art about their communities or families, but that’s the way many stories evolve. “Who are we? What do we have to say and who will hear it?” Each book is primarily and authentically made for its own community. (Not every Kids’ Own story has broad appeal. Most books that emerge do tell a story with universal themes — family love and devotion; pride in one’s culture and place — but not all of these tales translate into a narrative that engages people unfamiliar with the individual children or group. Indeed, the decision to release a book into the wider world is made by its community.)

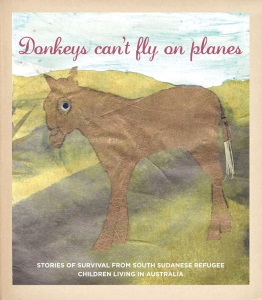

Donkeys Can’t Fly on Planes was published by Kids’ Own in 2012. Families from southern Sudan arrived in Australia as refugees and were resettled in Traralgon, a regional town in rural Victoria. Sharon Sandy, a teacher at the Latrobe English Language Centre in the town, heard the children’s stories and felt that they were ones “the world needs to hear.” Having seen the work of Kids’ Own elsewhere, she approached Victoria Ryle. Over a number of months, artist Lisa Gardiner traveled to Traralgon to work with the children. Lisa listened to their stories and led them in making collages to accompany their tales.

Donkeys Can’t Fly on Planes was published by Kids’ Own in 2012. Families from southern Sudan arrived in Australia as refugees and were resettled in Traralgon, a regional town in rural Victoria. Sharon Sandy, a teacher at the Latrobe English Language Centre in the town, heard the children’s stories and felt that they were ones “the world needs to hear.” Having seen the work of Kids’ Own elsewhere, she approached Victoria Ryle. Over a number of months, artist Lisa Gardiner traveled to Traralgon to work with the children. Lisa listened to their stories and led them in making collages to accompany their tales.The collection of short narratives takes its name from one child’s memoir about Steven, a much-loved donkey that was unable to come with a family when they fled. Other stories reveal encounters with giraffes and crocodiles; weddings; life in refugee camps in Kenya; and the challenges of adapting to life in Australia. The community members decided that they wanted the book to be available for sale, with all proceeds benefiting the Bor Orphanage & Community Education Project in Bor, South Sudan. As of this writing, the group has sold four thousand copies.

The book launch for Donkeys Can’t Fly on Planes was a triumphant celebration. ArtPlay (the city’s creative space dedicated to shared learning and art activities for children) hosted the event, where the authors and illustrators were dressed up and beaming for their first public reading and signing of copies for guests. Original artwork from the book hung in special frames gallery-style. Parents, friends, and families from Traralgon traveled two hours by train to be there. Renowned Australian author Arnold Zable spoke movingly of his admiration for the book. To add to the festivities, a donkey came, too.

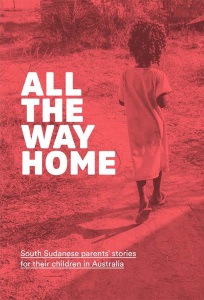

The Traralgon adults felt empowered by the children’s experience as authors and illustrators to share their own stories in two further Kids’ Own books, In My Kingdom and All the Way Home, launched in May 2015. Abraham Malual, a parent — and former child soldier — said, “The storytelling has increased in our homes and we feel like our children now respect our stories and understand finally who we are and where we have been. People didn’t know where we came from or why we came here. Now they understand.”

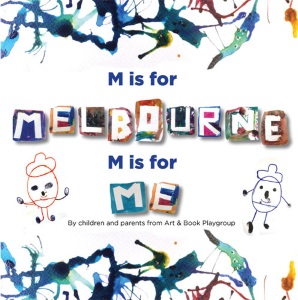

The Traralgon adults felt empowered by the children’s experience as authors and illustrators to share their own stories in two further Kids’ Own books, In My Kingdom and All the Way Home, launched in May 2015. Abraham Malual, a parent — and former child soldier — said, “The storytelling has increased in our homes and we feel like our children now respect our stories and understand finally who we are and where we have been. People didn’t know where we came from or why we came here. Now they understand.”Other recently published books include Who Is Your Mob?, a story made by Indigenous children from around Victoria who attend clinics at Melbourne’s Royal Children’s Hospital. Play Picnic explores artful food experiments by a group of preschoolers who are on the autism spectrum. The publisher’s 100th book, M Is for Melbourne, M Is for Me, explores the experiences and impressions of parents from diverse backgrounds who regularly meet at a playgroup at ArtPlay.

In the past, the challenges of producing offset printed books were significant. The long lead time needed for development, design, and printing meant that months could pass before the finished product appeared. Digital printing has enabled the affordable publication of both small and large print runs. High production values ensure that Kids’ Own books look and feel like real books. Each title has its own ISBN, and copies are lodged in relevant state libraries and the National Library of Australia.

Each book begins with the simplest of forms — the folded book from a single sheet of paper. Known as the “hot dog” or “origami” book, this quick and satisfying form (used by classroom teachers and artists the world over) can be achieved with the aid of the now-near-ubiquitous color photocopier. At a recent Children’s Book Festival at the State Library of Victoria, 140 books were written, illustrated, published, and read in a five-hour frenzy of book-making.

Each book begins with the simplest of forms — the folded book from a single sheet of paper. Known as the “hot dog” or “origami” book, this quick and satisfying form (used by classroom teachers and artists the world over) can be achieved with the aid of the now-near-ubiquitous color photocopier. At a recent Children’s Book Festival at the State Library of Victoria, 140 books were written, illustrated, published, and read in a five-hour frenzy of book-making.In 2014, the WePublish app was released. This takes the “hot dog” to a whole new level, with children and families able to create their own books using simple digital collage and images from their own photo libraries to tell their stories. A teacher from a remote Aboriginal community in Western Australia said, “It has been a massive hit with the kids, I have had visitors for three days straight making books. What an awesome way to build literacy skills (even on the holidays!).”

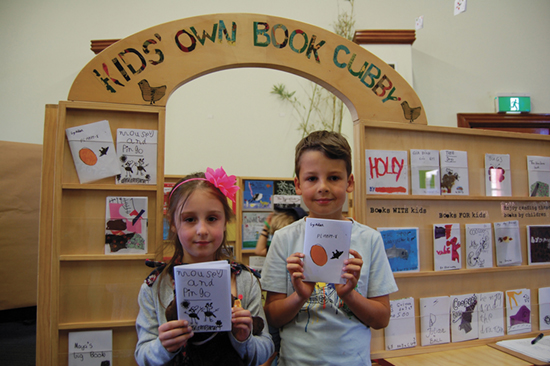

“Would you like to read my book?” is the cry of every author and illustrator: a book’s not a book till it’s read. To that purpose, in 2006 Kids’ Own designed and built a “Book Cubby” to be a pop-up publishing hub and portable display. Since then, libraries around Australia have purchased licenses to build their own cubbies; as of June 2015, eighteen have been built or are under construction. These versatile, child-sized interactive libraries are showcases for both “hot dog” books and published Kids’ Own titles; focal points for book-making in the community; and capsule displays of the lives, hopes, and dreams of many communities, many of which travel far beyond their own, all over Australia. The State Library of Western Australia’s book cubbies, for example, have traveled over eight thousand kilometers in three years.

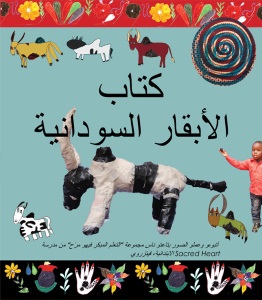

Artist-led publishing gives children the skills, knowledge, and confidence to make books on their own. In Ryle’s words, “It makes learning fun and it helps children from diverse cultures realize that ‘books and reading are for me.’” This publishing model also brings people together. It helps form new bonds between families and strengthens the sense of community. It gives parents and caregivers from a nonreading culture an understanding of the value of books and the importance of sharing rhymes and stories with their children. It encourages parents, especially those with English as a second language, to develop the skills to support their children’s reading. (Affordable digital printing means that books can also be printed in the children’s native languages and/or other languages. The Book of Sudanese Cows, for example, appears in Nuer, Dinka, and Arabic. Other books feature dialects from Myanmar and Timor-Leste.)

Artist-led publishing gives children the skills, knowledge, and confidence to make books on their own. In Ryle’s words, “It makes learning fun and it helps children from diverse cultures realize that ‘books and reading are for me.’” This publishing model also brings people together. It helps form new bonds between families and strengthens the sense of community. It gives parents and caregivers from a nonreading culture an understanding of the value of books and the importance of sharing rhymes and stories with their children. It encourages parents, especially those with English as a second language, to develop the skills to support their children’s reading. (Affordable digital printing means that books can also be printed in the children’s native languages and/or other languages. The Book of Sudanese Cows, for example, appears in Nuer, Dinka, and Arabic. Other books feature dialects from Myanmar and Timor-Leste.)What if every community made its own books? What if children could tell their own stories, in their own words, and have that honored and preserved in a beautiful book that they could share with others in their community? What would be the cumulative effect of this book sharing? We’d have a world where books by children for children strengthened culture, language, and literacy for all. Last year, a participant in a bookmaking workshop put it more bluntly: “For some children, it may be the only chance they have to tell their story.”

From the September/October 2015 issue of The Horn Book Magazine.

RELATED

RECOMMENDED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!