2018 School Spending Survey Report

Do Great Work and the Rest Will Follow

Growing up in the heart of the South, I saw firsthand how people were excluded based on skin color.

Growing up in the heart of the South, I saw firsthand how people were excluded based on skin color. I was taught that the rules weren’t the same for blacks and whites, but I also witnessed game-changers such as John Lewis and Coretta Scott King, who rose in spite of that fact. I never thought that being black or a woman would preclude me from any opportunities in life. I graduated in the top ten percent of my high school class and got into every college to which I applied.

Growing up in the heart of the South, I saw firsthand how people were excluded based on skin color. I was taught that the rules weren’t the same for blacks and whites, but I also witnessed game-changers such as John Lewis and Coretta Scott King, who rose in spite of that fact. I never thought that being black or a woman would preclude me from any opportunities in life. I graduated in the top ten percent of my high school class and got into every college to which I applied.My mother, an educator and guidance counselor, took me on a tour of my top ten schools. We met with professors, financial aid officers, and other students so that I could make an informed decision. My mother had been discouraged from pursuing her own dreams of becoming a singer, and so she always nurtured my talent. Although she herself couldn’t draw a straight line, she knew that my success would depend on my choosing a strong art program. The great news was that schools wanted me. The bad news was that most scholarships went to science majors and athletes. Undeterred, I took out thousands of dollars in loans — money I wasn’t sure I’d ever make back as an artist.

Syracuse University was my first choice. Though not in New York City (my childhood dream), it was the picture I had in my head of what college looked like. I had terrible anxiety surrounding the cost of college and the stigma of being labeled a starving artist, so I enrolled in communications design, taking illustration and creative writing as minors. I was one of only two black students in my class — both female. There was one other black student in the class ahead of me who took me under his wing as a baby designer. He pleaded with me to stay in design because, as he put it, “We need more black women.”

After my first year of design, I missed drawing and painting, and so I switched to illustration. I was then the only black female in that program. I found freedom as an illustrator and saw growth in my work. But I didn’t see myself reflected in illustration’s history. Where were the black editorial illustrators, comic makers, and book illustrators? Norman Rockwell was great, but his town didn’t look anything like mine. Maxfield Parrish was wonderful, but his angels and elves didn’t look like the ones in my head. Though most celebrated illustrators didn’t look like me, they were my only models.

After my first year of design, I missed drawing and painting, and so I switched to illustration. I was then the only black female in that program. I found freedom as an illustrator and saw growth in my work. But I didn’t see myself reflected in illustration’s history. Where were the black editorial illustrators, comic makers, and book illustrators? Norman Rockwell was great, but his town didn’t look anything like mine. Maxfield Parrish was wonderful, but his angels and elves didn’t look like the ones in my head. Though most celebrated illustrators didn’t look like me, they were my only models.I spent a semester studying abroad in Florence, Italy, and then returned to Syracuse for my senior year. There, I found that one of my instructors was Yvonne Buchanan, a black female illustrator. I was really excited to see her published work, which primarily reflected African American history. I also remember being introduced to the art of Jerry Pinkney, which made me think, “If this is what illustration is, I have a long way to go!” But I’d found a spark. I began studying the field more on my own and developing projects that might move my career forward. I worked with a local author in Atlanta that summer and made my first picture book dummy.

Senior year ended, and my future was uncertain. I had sent out promotional postcards and gotten some nice feedback, but nothing loomed on my horizon. Still, I returned home to Atlanta optimistic. I had my degree and was confident in the knowledge and experience I had gained. After some time, I landed some small freelance illustration jobs — including an easy reader with Jen Frantz, a young editor at Lee & Low Books — made a few more failed attempts at getting picture book work, and painted some commissioned portraits. Eventually a full-time position for an art teacher with the Atlanta Public Schools opened up and I took it, promising myself I would apply to grad school once my three-year provisional was up. While reading to my students every morning, I finally found myself in the pages of books like Storm in the Night, C.L.O.U.D.S., and Dancing in the Wings. These stories were about kids whose experiences reflected my own. Seeing those books gave me permission to explore ideas that interested me. I was ready to move on to the next phase of my art journey.

During my third year of teaching, I was accepted into the MFA Illustration as Visual Essay program at the School of Visual Arts (finally — New York City!). I worked alongside nineteen other talented artists, and four of us immediately made ourselves known as “the book illustrators.” My competitive nature was fully engaged as part of “the fabulous four.” For two years, we shared books, critiqued and encouraged one another, did group portfolio drop-offs, and met with publishers. When graduation came, two members of our group — Jonathan Bean and Taeeun Yoo — landed book deals immediately, then Lauren Castillo, but not me. I was talented. I worked hard. I had knowledge of the industry and had been published in the past. I hit the pavement with my portfolio, thinking surely someone would use me, but nothing happened.

During my third year of teaching, I was accepted into the MFA Illustration as Visual Essay program at the School of Visual Arts (finally — New York City!). I worked alongside nineteen other talented artists, and four of us immediately made ourselves known as “the book illustrators.” My competitive nature was fully engaged as part of “the fabulous four.” For two years, we shared books, critiqued and encouraged one another, did group portfolio drop-offs, and met with publishers. When graduation came, two members of our group — Jonathan Bean and Taeeun Yoo — landed book deals immediately, then Lauren Castillo, but not me. I was talented. I worked hard. I had knowledge of the industry and had been published in the past. I hit the pavement with my portfolio, thinking surely someone would use me, but nothing happened.My mother had taught me to exhaust every possibility before looking to another solution, so that’s what I did. My friends helped me stay positive in those dark months. I sought guidance from Pat Cummings, who was one of the only other working black women book illustrators I knew at the time. Pat gave me a lead on part-time work assisting illustrator Christopher Myers, and on a design job where I was the only black person working in the children’s art department. I showed my colleagues my own illustration work and was told it was nice, but no book contract followed. A few weeks later, I took in samples of two of my friends’ work, and they both got offers within the month. What a blow to my ego! I was frustrated, then sad, and then angry. I worked harder and stopped making images that I thought editors wanted to see. Instead I made images that I enjoyed.

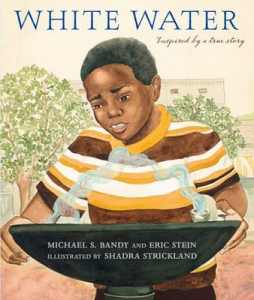

Through a serendipitous encounter at the 2007 Original Art Show opening with editor Jen Fox, then at Lee & Low Books, I landed my first big manuscript, where I found an opportunity to use the ideas and visual language that I had been experimenting with all along. That opportunity launched my career. I won the 2009 Coretta Scott King/John Steptoe Award for New Talent and the Ezra Jack Keats New Illustrator Award for Bird, written by Zetta Elliott.

Through a serendipitous encounter at the 2007 Original Art Show opening with editor Jen Fox, then at Lee & Low Books, I landed my first big manuscript, where I found an opportunity to use the ideas and visual language that I had been experimenting with all along. That opportunity launched my career. I won the 2009 Coretta Scott King/John Steptoe Award for New Talent and the Ezra Jack Keats New Illustrator Award for Bird, written by Zetta Elliott.It’s strange being black and a woman in a field that has historically celebrated white male contributions. Before I was published, I wondered if the only way in was to write and illustrate stories about slavery and black history. When all of my graduate school friends landed book contracts before me, at times I thought, “Is it because I paint black people?” I talked myself down from that ledge, but why was I up there to begin with?

After my books were out in the world, interviewers would ask questions like, “Why do you only paint black people?” To which I would reply: My choice of characters isn’t what defines my style; it’s how I paint them and the world around them. Would you ask a white male artist why he doesn’t paint black people?

My New York chapter closed after eight years. I went home to Atlanta, with plans to try living in Paris for a year. During that time, though, my mother lost two brothers and an aunt, and I was glad to be there to support my family. Paris would have to wait. Coincidentally, illustrator R. Gregory Christie, whom I had met in New York, had recently moved to Atlanta. One day over lunch he encouraged me to apply to a position at Maryland Institute College of Art, having already given the search committee my name. I applied, gathering up all of my stories, successes, and failures from the past. The next adventure was calling.

My New York chapter closed after eight years. I went home to Atlanta, with plans to try living in Paris for a year. During that time, though, my mother lost two brothers and an aunt, and I was glad to be there to support my family. Paris would have to wait. Coincidentally, illustrator R. Gregory Christie, whom I had met in New York, had recently moved to Atlanta. One day over lunch he encouraged me to apply to a position at Maryland Institute College of Art, having already given the search committee my name. I applied, gathering up all of my stories, successes, and failures from the past. The next adventure was calling.As a professor of illustration, I understand how important it is to be visible and accessible to other artists who are looking for guidance. I now have a range of books under my belt, and my attitude about the industry has certainly shifted. Looking to the future, in addition to collaborating with talented authors I know that I will be illustrating stories I write myself, and I will do my part in reflecting a more inclusive vision of our world. The industry still has a way to go in publishing stories that reflect our diversity. As an artist and illustrator of picture books, I look forward to being a model for those who are looking for themselves in their pages.

From the March/April 2014 issue of The Horn Book Magazine: Special Issue: Illustration.

Click the tag HBBlackHistoryMonth16 for more articles in this series.

RECOMMENDED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!

Shadra

Many thanks, Sam. I hooe you enjoy the book!Posted : Mar 04, 2014 11:42

Sam Juliano

Wonderful post in every sense! Your illustrations for BIRD are magnificent. I am a proud owner of that book. I can't wait for PLEASE LOUISE!Posted : Mar 04, 2014 03:36