2018 School Spending Survey Report

Foreign Correspondence: New House on the Block: Private Children’s Libraries in China

After Taotao, a Chinese preschooler, paid a first visit to the public Capital Library in Beijing in 2010, the boy’s mother posted an entry to her blog: “There are not many picture books in the library.

So Taotao’s mother decided to look further. Having learned about neighborhood “children’s book houses” from other moms, she did some research online and found one of these private libraries just ten minutes from her home. Yizhuang Children’s Library for Public Good, located in the clubhouse of an apartment community in southeast Beijing, is a reading room run by volunteers and open only on Saturday mornings. Taotao’s mother observed that the books appeared to be in good shape and that the majority were imported picture book titles. Mayi he Xigua [Ants and the Watermelon], the Chinese edition of a picture book by Japanese illustrator Shigeru Tamura, quickly became Taotao’s favorite.

Reading the books in-house was free. For the privilege of checking out books, up to five titles at a time, the library charged 50 yuan of deposit and 150 yuan of annual membership fee (totaling about $32). Taotao’s mother hesitated at first, considering the limited hours of the reading room, but her decision was made easy by Taotao’s loud chanting: “I want to take Ants and the Watermelon home!” The family paid for the membership and left happily with five books.

Story hour at the Aiding Island Happy Shared Reading House, Beijing. Photo courtesy Aiding Island.

Story hour at the Aiding Island Happy Shared Reading House, Beijing. Photo courtesy Aiding Island.Yizhuang Children’s Library is one of numerous privately run facilities that now cater to young children’s reading needs in China. In Shanghai in July 2006, a Taiwanese investor launched the House of Aesop’s Fables, advertised as China’s first “professional story house.” Offering story hours and a toy room, the Aesop House received instant public attention during the first week of its operation, when services were free and families waited in long lines for their turn for story hours in rooms decorated like mini–theme parks. However, children all but disappeared once the commercial enterprise started selling tickets priced at 80 yuan for approximately an hour’s story time, plus 20 yuan if parents wished to accompany their kids.

News coverage of the Aesop House nonetheless raised awareness of the benefit of story time for young children’s literacy development and emotional needs — and to the lack of such programs in existing public libraries in China. Since then, private children’s reading rooms and story houses have grown at an accelerated pace in China, mostly in big cities in the east. These story houses all seek to meet needs where state-owned public institutions have failed, but the private collections vary widely in size, membership pricing, types of services, and the professional background of personnel. At one end of the spectrum are not-for-profit organizations such as the Beijing-based Delicious Reading Feast, which has received grants from private foundations and has focused on promoting reading among elementary school children of migrant workers in Beijing. At the other end are membership children’s libraries such as the Harbin-based Bell Children’s Book Club, charging an annual fee of 900 yuan (or $143) for checking out books and attending programs; or Kuaile Kaishi Yuanban Shao’er Yingwen Tushuguan [Happy-Start English-Language Children’s Library], which, located in an apartment unit in Beijing, has extended its business from book circulation and children’s programs to classes and English immersion courses; or Anniekids.org, which practices a franchising business model, offering both imported books and training to people who plan to open their own membership children’s libraries. Some three dozen Annie Kids franchises have spawned in thirteen provinces and municipalities.

An enticing array of picture books: Aiding Island Happy Shared Reading House. Photo courtesy Aiding Island.

An enticing array of picture books: Aiding Island Happy Shared Reading House. Photo courtesy Aiding Island.The rise of private children’s libraries in China has closely followed the development of the Chinese picture book market since 2000. Chinese readers are no strangers to popular illustrated story books (called lianhuanhua, or “linked images”) and comic books, but the format of picture books suitable for preschoolers and beginning readers didn’t take off until the past decade, when people born around the end of the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976) were starting families. Since the turn of the twenty-first century, the largest cohort of Chinese babies have been born into emerging middle-class families, each nurtured as an only child by the best-educated generation of fathers and mothers in Chinese history. (China’s illiteracy rate was estimated to be 85%–90% of the total population at the turn of the twentieth century; that figure lowered to 6.72% in 2000.) It was in this economic and cultural context that board books and picture books were increasingly embraced by young parents for the education and entertainment of their children. The collection, space, and services of Chinese public libraries, however, remained poorly prepared for young patrons not capable of independent reading, thus creating market space — to borrow a term from the business world — for privately run children’s libraries.

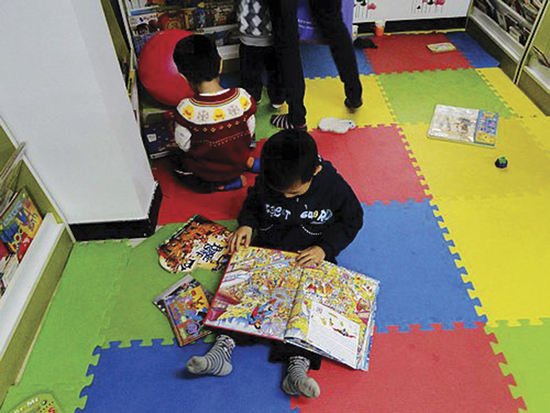

Engrossed in a book at the Happy-Start English-Language Children's Library, Beijing. Photo courtesy Happy-Start.

Engrossed in a book at the Happy-Start English-Language Children's Library, Beijing. Photo courtesy Happy-Start.The focus on younger and emergent readers is reflected in the names of these private libraries (many call themselves huiben guan, or “picture book houses”), and their publicity materials frequently mention the term qinzi yuedu (“parent-child shared reading”). The ample leisure time that Chinese preschoolers enjoy makes them an appropriate targeted age group. Driven by high-stakes standardized testing, China’s education system has long been accused of discouraging reading for pleasure among school-age children: the higher the grade level, the less leisure reading is possible after school.

Foreign influences on service practices, book collections, and professional guidance in these libraries are manifest and have entered mainland China from multiple channels. The Taipei-based Hsin-Yi Foundation, which has worked on promoting early childhood education in Taiwan since the late 1970s, opened a branch company in Nanjing, China, in 2005, duplicating its picture book publishing business and reading promotion activities in a much larger market. Chinese mothers who had pursued advanced degrees in Western countries returned to China to find that they would lose the free and easy access to juvenile books and entertaining programs they had enjoyed in public libraries overseas. A determination to replicate that rich literary environment was the initial motivation of several well-known membership libraries. Their managers were young mothers returning from the United States, Canada, Britain, and Hong Kong.

In terms of book selection, major children’s book awards in the U.S. and Europe, as well as various book lists compiled by The New York Times and American librarians, frequently inform Chinese publishers, story houses, and parents what titles to import and translate, add to the collection, and check out for children. Classic titles by Maurice Sendak, Eric Carle, Margaret Wise Brown, and Dr. Seuss, whether in the original English edition or Chinese translation, are as appealing to many toddlers who visit private libraries as they have been to generations of American children. Interactive books such as flip-ups and pop-ups, and books in cloth and other nonpaper materials, are popular novelties that have expanded Chinese ideas of what a children’s book can be. Series books are as popular in China as they have been in the West, familiarizing young Chinese readers with the Berenstain Bears, Clifford the Big Red Dog, Corduroy, Frog and Toad, Olivia, The Magic School Bus, Dora the Explorer, and so on. Chinese markets have also widely welcomed titles introduced from Japan, Australia, and Europe. The picture book Mr. Gumpy’s Outing by British author-illustrator John Burningham and the Les P’Tites Poules series by the French author-illustrator team Christian Jolibois and Christian Heinrich have widely charmed three- to six-year-olds.

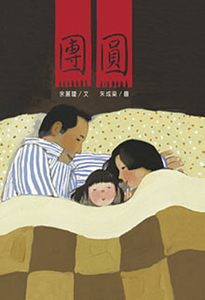

Titles by indigenous Chinese creators tend to rank lower in popularity, an issue that has long caused educators discomfort. The Nanjing Hsin-Yi company was thus especially proud when the first original picture book it edited — Tuanyuan [A New Year’s Reunion] (2008) — was sold to Candlewick Press and subsequently made The New York Times 2011 Best Illustrated Children’s Books list.

Titles by indigenous Chinese creators tend to rank lower in popularity, an issue that has long caused educators discomfort. The Nanjing Hsin-Yi company was thus especially proud when the first original picture book it edited — Tuanyuan [A New Year’s Reunion] (2008) — was sold to Candlewick Press and subsequently made The New York Times 2011 Best Illustrated Children’s Books list.In China, English is a required course from elementary school through college. An emphasis on English-language books in many private children’s libraries — as well as English programs and classes they offer — caters to those parents who wish to give their preschoolers a head start in the acquisition of a foreign language. However, parents’ English skills vary widely, contributing to the marketing success of leveled books such as the I Can Read series. Those straightforward numbers labeled on book covers greatly ease some Chinese parents’ anxiety over navigating the foreign language collection and selecting the right title for their child. Not too confident about their own English vocabulary, pronunciation, and even reading comprehension of kids’ books, Chinese parents have also sought books with read-alouds in either audio or video format, ideally narrated by native English speakers.

Programs for children and families are a significant part of many private libraries. Private libraries have provided read-alouds, storytelling, crafts, art classes, English classes, and holiday parties. Current trendy offerings include English phonics lessons and baking sessions. For adults they organize workshops and lectures on shared reading, recommended children’s titles, and parenting topics. Creative use of online communication tools enhances the effectiveness of library services. Blogs are heavily used to highlight book titles, publicize events, and collect feedback from parents. Generous postings of photos and videos from program sessions serve to attract potential families. Managers tend to adopt a friendly, peer-to-peer tone in blog entries, and respond to comments in a timely and respectful manner, thus differing from a top-down, one-way communication model seen in state-owned public library websites.

What is conspicuously missing in China’s spontaneous membership children’s libraries movement is the involvement of professionals trained in library services for youth. A quick scan of personal background information volunteered by more than a dozen active story house owners found no mention of library and information science. Indeed, the absence of professional children’s librarians in China is one of the factors that explain the growing popularity of private libraries. On the other hand, at least two cases suggest that the boundaries between public and private sectors, between professionally trained librarians and self-taught parents, are not impermeable.

The Aiding Dao Qinzi Yuedu Guan [Aiding Island Happy Shared Reading House] is a rare private library that has collaborated with LIS professionals, adopting the Chinese Library Classification System to completely reorganize its collection of 5,000 titles. In another unique case, the Beijing-based nonprofit New Generation Foreign Language Library is now recognized as a branch library of the (public) Capital Library in Beijing. The latter has received donated English-language children’s books from an American foundation — likely after Taotao’s disappointing visit that opened this article — that greatly enriched New Generation’s collection. Private libraries have also conducted outreach programs, bringing story time and program hours to public schools and public children’s libraries.

What will the future of Chinese membership children’s libraries be? Will they prompt Chinese library schools to open up professional training and scholarly research in youth services and elevate the quality of children’s services across the board? Will they motivate public libraries to improve outdated services? It’s true that the Capital Library’s collection and space design for very young children have greatly improved since Taotao’s excursion two years ago.

However, on April 26, 2012, another mom took her child to the toddlers’ area of the Capital Library and posted a blog entry reflecting her disappointment with the experience: her two-and-a-half-year-old son, excited by the many choices of attractive books, was repeatedly told by the public librarian to stop making so much noise, which his mother saw as a harsh rebuke and a disregard for children’s needs. As things stand, the public institutions still have a lot of catching up to do, making Chinese private libraries all the more important in their mission to support literacy and literature for children.

From the September/October 2012 issue of The Horn Book Magazine.

RELATED

RECOMMENDED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!