2018 School Spending Survey Report

Foreign Correspondence: The Little Bookroom

“When we heard that a young man was to open a specialist children’s bookshop…we were all amazed at his fortitude and foolhardiness.

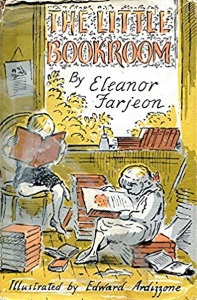

The Little Bookroom's logo, originally commissioned from Edward Ardizzone

“When we heard that a young man was to open a specialist children’s bookshop…we were all amazed at his fortitude and foolhardiness. We very much feared the venture would not last long. Everyone was delighted…that it had not only lasted, but prospered.”

Publisher and broadcaster, author of British Children’s Books in the Twentieth Century, Frank Eyre delivered these opening remarks at The Little Bookroom’s twenty-first birthday party in 1981.

Albert Ullin, founder of The Little Bookroom, has influenced and nurtured many Australian authors and illustrators. Today The Little Bookroom thrives, fifty-seven years after its opening (under the ownership of Leesa Lambert and her family) in a leafy inner suburb of Melbourne — one of the oldest children’s bookstores.

Ullin arrived in Melbourne in 1939 as a nine-year-old, fleeing pre-war Germany via Italy with his family. The Ullins were part of the Wertheim family — makers and sellers of sewing machines and pianos worldwide — and a great-uncle had come to Australia in 1875, so relatives were able to sponsor their immigration. Ullin’s love of art and appreciation of story began early. He remembers as a child poring over Edmund Dulac’s illustrations of The Snow Queen and re-telling the story to his teddy and his toy rabbit Christina. He spoke no English but the family settled into Melbourne life — Albert and his brother attended a public school where he won prizes: “For Geography, and books of course!”

His apartment is a book-worshipper’s paradise. Glass-fronted bookcases of polished dark wood crowd the living room, competing for wall space with original artworks and prints. The visitor coming through the front door squeezes past one which houses many of Eleanor Farjeon’s books, including many of her now-forgotten adult novels.

In her author’s note for The Little Bookroom, first published in 1955, Farjeon said:

"In the home of my childhood there was a room we called ‘The Little Bookroom.’ True, every room in the house could have been called a bookroom. Our nurseries upstairs were full of books. Downstairs my father’s study was full of them. They lined the dining-room walls, and overflowed into my mother’s sitting-room, and up into the bedrooms. It would have been more natural to live without clothes than without books. As unnatural not to read as not to eat…A lottery, a lucky dip for a child who had never been forbidden to handle anything between covers…worlds filled with poetry and prose and fact and fantasy…Here, in The Little Bookroom, I learned, like Charles Lamb, to read anything that can be called a book."

With characteristic Australian cheek or chutzpah, when establishing his bookshop Ullin wrote to Farjeon and illustrator Edward Ardizzone to request the use of the name and an illustration to be his logo. (He’d wanted to call the shop Albert’s Books but a similar name was already in use by a Perth bookstore.) Farjeon’s letter granting permission expressed her delight that she regarded Melbourne was “one of ‘my’ cities.” Her father, B. L. Farjeon, had sought his fortune on the Victorian goldfields in his youth, and wrote a book about his adventure called The golden land, or, Links from shore to shore in 1890.

With characteristic Australian cheek or chutzpah, when establishing his bookshop Ullin wrote to Farjeon and illustrator Edward Ardizzone to request the use of the name and an illustration to be his logo. (He’d wanted to call the shop Albert’s Books but a similar name was already in use by a Perth bookstore.) Farjeon’s letter granting permission expressed her delight that she regarded Melbourne was “one of ‘my’ cities.” Her father, B. L. Farjeon, had sought his fortune on the Victorian goldfields in his youth, and wrote a book about his adventure called The golden land, or, Links from shore to shore in 1890.In Australia in the 1950s, children’s books were seldom promoted except during Christmas and the fledgling Children’s Book Council of Australia’s annual Book Week. “My first school holiday job was in Spiegel’s, a stationer, parceling up books during a Christmas rush. There was a narrow staircase out the back and I remember a roll of cellophane down it to make it easy to cut it to size. No Christmas paper after the war.” Australian authors and illustrators were published almost exclusively out of Great Britain, and there were few local picture books. Ullin drew attention to these few by keeping them shelved separately in The Little Bookroom when it opened. For the first few years, Ullin says, “My biggest sellers were Richmal Crompton’s Just William books, W. E. Johns’s Biggles, and the Hugh Lofting (Doctor Doolittle) and Arthur Ransome titles. I didn’t stock Enid Blyton — she was available everywhere.” He began importing paperbacks and picture books from the U.S. and remembers the impact of the rapidly expanding YA — in particular, John Donovan’s I’ll Get There. It Better Be Worth the Trip. School libraries were rapidly developing at this time, and with public libraries were Ullin’s mainstay, as well as parents and other interested adults who discovered the shop in a city laneway. The first shop was in the Metropole Arcade, now demolished. He then moved to Equitable Place, and then to Elizabeth Street. Branches of The Little Bookroom were established in the suburbs of Melbourne and in the nearby city of Geelong.

Ullin acknowledges the visionary editor and publisher Anne Bower Ingram as the prime mover in the golden age for Australian picture books. Ingram worked for the publisher William Collins and, beginning in the 1970s, championed many new Australian authors and illustrators. Among her successes were the first commercially successful titles by Indigenous artists and storytellers Dick Roughsey and Percy Tresize, Junko Morimoto, and Bob Graham who have won awards at home and worldwide for their work. “It was an exciting time,” Ullin says, and he was nurturing emerging talent himself during this time through his involvement with the Children’s Book Council of Australia. “The Little Bookroom became a meeting place for those who saw children’s literature as a profession.” He served as president of CBCA Victoria, and built up their fundraising by drawing on his friendship and patronage of artists. “A very young Roland Harvey designed bookmarks for us and they sold like hotcakes.”

At that time, the Melbourne Teachers College led by visionary teacher George Holman produced children’s literature luminaries The Little Bookroom was just five blocks from the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology University’s art school. One young student would come in and sit cross-legged in front of the picture book shelves, pulling them out and looking at them for hours. This was Ron Brooks, who went on to create pictures for Jenny Wagner’s The Bunyip of Berkeley’s Creek published in 1973. When Ullin saw it, he was “swept off my feet by it. So much to read in it.” He bought original artwork from the book from the artist and this was the start of his dedicated collecting. Brooks dragged his classmate from RMIT in as well: Peter Pavey became a frequent visitor and went on to publish the award-winning One Dragon’s Dream. Later, Brooks and Wagner repeated their successful partnership in John Brown, Rose and the Midnight Cat. Ullin is the proud owner of a toy Old English sheepdog in John Brown’s likeness, made by a friend of author Jenny Wagner. “She sold it to me to help pay her telephone bill.” (Dog-averse visitors to his apartment have been known to ask for the toy to be hidden before they arrive.)

Ullin’s own knowledge was expanded by visits to “that magical place, Bologna” as well as a fellowship to study illustrations of Grimms’ fairy tales at the Internationale Jugendbibliothek (International Youth Library) in Munich. He was a regular visitor to the United States to attend the American Booksellers Association conventions in major cities, and was rendered temporarily speechless upon meeting his idol Maurice Sendak in New York. Half a bookcase in his apartment today contains editions of Sendak’s work.

Ullin first saw Sendak’s work in detail in the 1964 Weston Woods film The Lively Art of Picture Books. “I was fascinated with his process, the first version of Wild Things that was a tiny book made of strips of paper. I had never written a fan letter before, but I sent one to him.” Sendak replied with an invitation to come and see him if ever Ullin was in New York. A few years later, Ullin took him up on the invitation. “We met in Greenwich Village for a meal. It didn’t go well, I was over-awed, silence after silence in the conversation. Sendak was about to leave when he asked Ullin what he admired about Where the Wild Things Are. The reply — that he could “hear the music behind it” — led to more coffee and a long chat, further meetings and the presentations of signed copies of books and an engraving from A Kiss for Little Bear.

Albert Ullin (right) and author John Marsden at the opening of the exhibition Bunyips and Dragons at the National Gallery of Victoria in 2015

Albert Ullin (right) and author John Marsden at the opening of the exhibition Bunyips and Dragons at the National Gallery of Victoria in 2015Recently Ullin donated ninety-three original illustrations, representing forty years of collecting, to the National Gallery of Victoria. Over sixty of them were shown by the NGV in an exhibition, Bunyips and Dragons: Australian Children’s Book Illustrations, which ran from July to October 2015. As well as the illustrators mentioned above, there were works by esteemed artists Shaun Tan, Graeme Base, Julie Vivas, Patricia Mullins, and Terry Denton. At the opening, Ullin stated that “In the 1960s photography in Australia was not regarded as an art form. In the same way, children’s book illustration is not recognized as art in its own right, and through my gift I hope to change that.” The director of the National Gallery of Victoria, Tony Ellwood, praised the exhibition as “providing an entry point to the NGV via familiar and much-loved childhood illustrations.” One wall of the exhibition was a reproduction of a pen-and-ink drawing of The Little Bookroom in Elizabeth Street as it was on its twenty-first birthday.

Since retiring from the bookshop, Ullin has worked with the Children’s Literature Australia Network. A mentorship program for emerging writers and artists of children’s books, named for Maurice Saxby under the auspices of the May Gibbs Children’s Literature Trust. Run as part of the city of Stonnington’s Literature Alive Festival, a local government in suburban Melbourne, CLAN pairs emerging creators with practitioners of the thriving Australian book scene. Last year, there were over 400 Australian-published entries in the CBCA’s prestigious annual awards. Melbourne’s designation as a City of Literature by UNESCO in 2008 acknowledges the capital of Victoria’s proud history of reading, writing, publishing and bookselling. Current public debate about the government’s proposed removal of parallel importation restrictions on books emphasizes literature as “our most successful cultural industry.”

Australia’s first Children’s Laureate Alison Lester (co-honoree with Boori Monty Pryor) wrote an inscription in Albert Ullin’s copy of her 2004 multi-award-winning picture book Are We There Yet? It read, I’m honoured to be in your collection.

Also read Margaret Robson Kett's article "Kids' Own Publishing" from the September/October 2015 issue of The Horn Book Magazine.

RELATED

RECOMMENDED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!