Face Out: Picture Book Covers

A recent conversation about the current state of the picture book soon came around to the subject of book jackets.

A recent conversation about the current state of the picture book soon came around to the subject of book jackets. A senior art director in the group noted mournfully that as jacket designs have increasingly become the province of sales and marketing teams, covers have grown less representative of the books they trumpet. The disconnect can take different forms. The typeface chosen for the cover may be out of sync with that used for the interior text, and the cover graphic may be a noisy attention-grabber there to announce, “I am a big, important book, so buy me!” The eye-popping cover image of Robert Byrd’s Electric Ben: The Amazing Life and Times of Benjamin Franklin (Dial), for example, is like a souped-up, funny-car version of the capable, but far quieter, artwork found inside the book. Additionally, the trim size may be larger than feels right for the story told: The Further Tale of Peter Rabbit (Warne), by Emma Thompson, with illustrations by Eleanor Taylor, inhabits a much bigger format than Beatrix Potter’s original, the better to make the book show up on store shelves but not, I wouldn’t think, to draw small children into Peter’s furtive, hazard-filled, hide-and-seek world.

A recent conversation about the current state of the picture book soon came around to the subject of book jackets. A senior art director in the group noted mournfully that as jacket designs have increasingly become the province of sales and marketing teams, covers have grown less representative of the books they trumpet. The disconnect can take different forms. The typeface chosen for the cover may be out of sync with that used for the interior text, and the cover graphic may be a noisy attention-grabber there to announce, “I am a big, important book, so buy me!” The eye-popping cover image of Robert Byrd’s Electric Ben: The Amazing Life and Times of Benjamin Franklin (Dial), for example, is like a souped-up, funny-car version of the capable, but far quieter, artwork found inside the book. Additionally, the trim size may be larger than feels right for the story told: The Further Tale of Peter Rabbit (Warne), by Emma Thompson, with illustrations by Eleanor Taylor, inhabits a much bigger format than Beatrix Potter’s original, the better to make the book show up on store shelves but not, I wouldn’t think, to draw small children into Peter’s furtive, hazard-filled, hide-and-seek world.The jacket as a selling tool, rather than as merely the protective wrapper (or “dust jacket”) it started out as more than a century ago, is hardly a new phenomenon. But as the major market for children’s books shifted from libraries and schools to retail from the 1970s onward, and as the publishing industry itself went corporate and redrew its organizational chart, cover designs rooted in editorial vision became a good deal rarer. Jackets produced as a group decision, with the marketing and sales force of the house taking the lead, became the new norm.

A devil’s advocate might interject here that children tend to love glittery lettering, shiny Mylar surfaces, and gold tinsel spines; and if amusing cheap tricks like these lead to a love of reading, why complain? Even if there is a disconnect between a book’s content and its cover design, does that really matter? I would say that it matters whenever the result is a book that feels sadly at war with itself (the oversized Peter Rabbit “sequel,” for example); and when a certain kind of cozy, intimate book for which there has long been a proven place falls by the wayside. The cover designs of Don Freeman’s Norman the Doorman (Viking) and Esphyr Slobodkina’s Caps for Sale (Harper) — to name two mid-twentieth-century picture books that attained “classic” status in time to withstand the current trend — would be unlikely to pass muster at any of today’s major publishing houses. True, both of these books date from the time when a new picture book was typically encountered up-close on a library shelf or table, not glimpsed at forty paces in a big box store, amid a crazy quilt of color-splashed alternatives. But whatever the market forces that happen to be at work, if the picture book as a genre is to thrive in the future, publishers will need to make books that have more to offer, from the cover on in, than calculated cleverness.

Consider two of the most beloved picture books of all time. What, besides their publisher (Harper) and editor (the late great Ursula Nordstrom), do Goodnight Moon and Where the Wild Things Are have in common? Stylistically, their illustrations look nothing alike and their story lines could hardly be more different. Still, these two perennial favorites do share one striking feature—and it is a pretty strange one when you stop to think about it: in both instances, the hero of the tale does not appear on the cover.

In a preliminary jacket sketch for Goodnight Moon, Clement Hurd painted a more static version of the cover image of the Great Green Room everyone knows. It’s pretty much the same design, except that in the sketch the bunny child perches on the windowsill, at the center of the picture. In the finished cover, the bunny has gone missing.

In a preliminary jacket sketch for Goodnight Moon, Clement Hurd painted a more static version of the cover image of the Great Green Room everyone knows. It’s pretty much the same design, except that in the sketch the bunny child perches on the windowsill, at the center of the picture. In the finished cover, the bunny has gone missing.Nearly all picture book covers make it their first order of business to introduce readers to the hero of the tale; it seems only good sense to do so. But when it was time to finalize the cover for Goodnight Moon, Nordstrom took a counterintuitive approach that reflected her understanding of the text’s mantra-like magic string of words. It was she who instructed Hurd to take out the bunny.

Nordstrom’s argument went something like this. The bunny was not a hero in the ordinary sense but rather a placeholder for the child at home who, swept up in the spell of Margaret Wise Brown’s hypnotic lyric, would want to imagine himself inside the Great Green Room. The story, she told the illustrator, wasn’t really the bunny’s story. Viewed this way, the jacket image came to serve as a door left open for the reader to enter the room.

But what about Where the Wild Things Are? Did Nordstrom, or Maurice Sendak, omit Max from the cover image for similar reasons? The situation is not quite comparable. Max, after all, is arguably the quintessential picture-book hero. The archival record does not seem to account for what happened. We know that Max does not make an appearance in any of the several Wild Things cover studies preserved at Philadelphia’s Rosenbach Museum & Library, which houses Sendak’s archives. But we don’t know why, and so can only guess what Sendak and Nordstrom were thinking. My guess would be this: the cover image was meant to be another open door, and a signal to readers that they were going to have to venture inside—inside the book and inside themselves — if they wished to have what the cover art promised would be a strange and wonderful experience. This was a cover to daydream over, not art to digest in an instant. And I doubt it would make it past any present-day publishing committee.

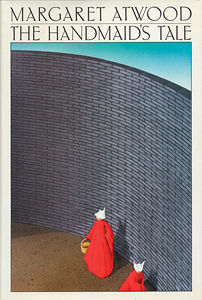

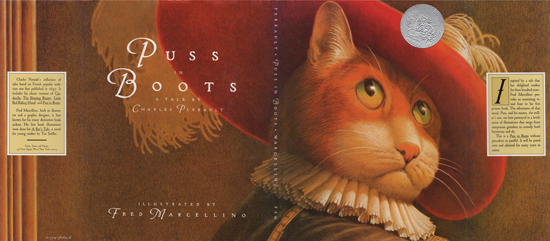

But what about Where the Wild Things Are? Did Nordstrom, or Maurice Sendak, omit Max from the cover image for similar reasons? The situation is not quite comparable. Max, after all, is arguably the quintessential picture-book hero. The archival record does not seem to account for what happened. We know that Max does not make an appearance in any of the several Wild Things cover studies preserved at Philadelphia’s Rosenbach Museum & Library, which houses Sendak’s archives. But we don’t know why, and so can only guess what Sendak and Nordstrom were thinking. My guess would be this: the cover image was meant to be another open door, and a signal to readers that they were going to have to venture inside—inside the book and inside themselves — if they wished to have what the cover art promised would be a strange and wonderful experience. This was a cover to daydream over, not art to digest in an instant. And I doubt it would make it past any present-day publishing committee.Which is not to say that a cover has to be quiet and contemplative to rate as a success. Fred Marcellino came to picture-book making in the early 1990s at the tail end of a brilliant run as America’s preeminent trade fiction jacket artist of the previous two decades. Chances are great that at some point you have been stopped in your tracks by the indelible graphics he created for Tom Wolfe’s The Bonfire of the Vanities, Anne Tyler’s The Accidental Tourist, Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale, and a host of other international bestsellers. No one knew better than Marcellino how to create a book jacket that made a big splash while also giving an incisive impression of the experience that lay in store for readers.

The funny thing is that when Marcellino turned to designing the cover of his first picture book, Puss in Boots (Farrar), a project he had dreamed of doing for years, he painted an irresistibly saucy, elegant close-up of the story’s egomaniacal cat — but forgot to leave room for the title or his name. Marcellino’s editor, Michael di Capua, came to the rescue with a bold solution that, he later reported, had been revealed to him in a dream: to leave the front cover entirely type-free. The graphically thrilling result, which set the stage for a trickster tale famous for its own surprising twists and turns, became the most talked-about juvenile cover design in recent memory. A second result was that Puss’s text-free headshot went on to inspire a Mount Rushmore of monumentally large — but overbearing and for the most part humorless — copycat jackets, especially for picture book biographies of JFK, Helen Keller, and other famous folk: the ultimate I’m-a-big-important-book covers. Which only goes to show that, whatever form it takes, the best picture book cover design is made from the inside out, as a strong, clear, highly particular response to a one-of-a-kind story worth discovering.

The funny thing is that when Marcellino turned to designing the cover of his first picture book, Puss in Boots (Farrar), a project he had dreamed of doing for years, he painted an irresistibly saucy, elegant close-up of the story’s egomaniacal cat — but forgot to leave room for the title or his name. Marcellino’s editor, Michael di Capua, came to the rescue with a bold solution that, he later reported, had been revealed to him in a dream: to leave the front cover entirely type-free. The graphically thrilling result, which set the stage for a trickster tale famous for its own surprising twists and turns, became the most talked-about juvenile cover design in recent memory. A second result was that Puss’s text-free headshot went on to inspire a Mount Rushmore of monumentally large — but overbearing and for the most part humorless — copycat jackets, especially for picture book biographies of JFK, Helen Keller, and other famous folk: the ultimate I’m-a-big-important-book covers. Which only goes to show that, whatever form it takes, the best picture book cover design is made from the inside out, as a strong, clear, highly particular response to a one-of-a-kind story worth discovering.

From the November/December 2012 issue of The Horn Book Magazine.

RELATED

RECOMMENDED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!

Sue Wars

I'm not in favor of truly misleading book covers in children's books or titles either for that matter. It is annoying when you view the book's cover for purchase or order on line and find out the content isn't at all what you expected as the cover may have indicated. Contemporary design may send an abstract message that is intriguing and you expect the unexpected content. It is pulling you in just as a clever connection-to-story image would do, and yet revealing the temperament of the content inside. And the door has opened to your minds eye. A pleasant experience.Posted : Apr 11, 2013 02:48

CL Frey

I've always loved Marcellino's Puss in Boots. Hearing the story behind its fabulous cover makes me love it even more. Thank you for the article!Posted : Dec 11, 2012 06:04

O Come All Ye Faithful? — The Horn Book

[...] Come All Ye Faithful? November 29, 2012 By Roger Sutton Leave a Comment Don’t miss Leonard Marcus’s latest column about picture book covers, and speaking of that, SLJ stalwart Rocco Staino reports on a gallery of ‘em that would make [...]Posted : Nov 29, 2012 06:45

Laura Purdie Salas

Great essay--that last line says it all. I'm open to lots of kinds of covers, but I do not want to be misled about what will follow. Can't wait to read your Madeleine L'Engle book, by the way. It's on my Christmas list!Posted : Nov 28, 2012 05:59

Martha Freeman

Is this really a trend? What about the subdued covers for Mo Willems' wildly successful pigeon books (or any of his books) and Jon Klassen's books?Posted : Nov 28, 2012 05:07