2018 School Spending Survey Report

Danger! Dialogue Ahead

When writing nonfiction, including dialogue can be a dangerous proposition.

When writing nonfiction, including dialogue can be a dangerous proposition.

When writing nonfiction, including dialogue can be a dangerous proposition.Several years ago, I asked an author about the snappy dialogue in his nonfiction picture book about a poet. He said the words were a combination of excerpts from the poet’s autobiography and some things the author “rather assumed.” The book, he continued, got “whacked in a couple of reviews.”

It wasn’t because the book was badly written. It was because it contained fabricated dialogue but was presented as nonfiction. This was a classification malfunction.

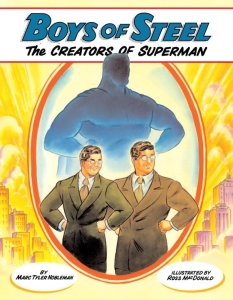

Early drafts of my nonfiction picture book Boys of Steel: The Creators of Superman did not contain dialogue. An editor I’d queried suggested I add some, but the word whacked had spooked me into feeling that any dialogue could nullify the nonfiction status. So I resisted.

Soon, however, I grew curious. I went back through the text and found instances where I could replace exposition with a punchy quotation from one of the published interviews from my source material. As luck would have it, these happened to occur fairly evenly throughout the manuscript.

That editor did not end up acquiring the book. And the one who did, Janet Schulman, felt that picture book biographies do not need dialogue. I told her I used to feel the same way, but now that I’d tried it, I liked the outcome. So Janet obliged me, and the dialogue stayed.

Avoiding the trap of making up quotations is not the only nonfiction dialogue danger. While doing market research for Boys of Steel, I came across reviews dinging eight nonfiction picture books for lack of attribution in the back matter. (This was in terms of both quotations and facts in general.)

Still seeing whacked warning signs, I asked Janet if the acknowledgments in the book could include the following: “All dialogue is excerpted from interviews with Jerry and Joe” (referring to writer Jerry Siegel and artist Joe Shuster, the creators of Superman). At first, she didn’t think it was necessary. To try to validate my request, I referenced the eight tsk-tsk reviews I’d found and the poet-profiler’s unpleasant experience in the dialogue trenches. Janet kindly obliged me again.

Though I’d lobbied to insert that disclaimer, even I was surprised when it was singled out in the very first review (Booklist): “A bibliography and assurances that ‘all dialogue [was] excerpted from interviews’ puts factual muscle on the narrative.” Janet graciously joked that I should now blog about how something my editor initially dismissed became a focal point of the first review. (So I did.)

Avoiding made-up dialogue and citing sources are straightforward obligations. A trickier prospect is addressing the authenticity of dialogue not in and of itself but rather with respect to context.

Technically, no nonfiction book is pure nonfiction. Even if every word of every quotation can be corroborated, the bugaboo is the placement of those quotations.

In other words, while a quotation may be “real,” it may not necessarily have been spoken at the chronological moment it appears in the book’s narrative. That makes many lines of dialogue at once true and false. Let’s call them nonfictionesque.

I ran into some nonfictionesque problems in Boys of Steel. Consider this passage about Jerry:

“He had crushes on girls who didn’t know — or didn’t care — that he existed. ‘Some of them look like they hope I don’t exist,’ Jerry thought.”

This is how the statements appeared in the source, a published interview with Jerry:

“I had crushes on several attractive girls who either didn’t know I existed or didn’t care I existed. As a matter of fact, some of them looked like they hoped I didn’t exist.”

(Side note: How could a writer read that and not put it in his book?)

I had to change the tense of the original lines, and I tightened them, too. However, that did not change the meaning; while it took a few nonessential words out of Jerry’s mouth, it did not put words in.

Writers of nonfiction must often make such judgment calls. History is heavy with what people did but comparatively scant on precisely what people said. Therefore, when writers do find a lively statement in a primary source, to my mind readers benefit by allowing the writer a pinch of leeway in how he incorporates it. So long as it’s cited, far better to tweak a tense than dispose of a gem altogether for fear of the fury of the fact checker. This further informs a definition of nonfictionesque.

But what of the context? Yes, Jerry did say the quotation above, but it was in an interview decades after the fact, not in the 1930s, which is when I positioned it in my narrative. That is one reason why I used the word thought instead of said. It was my inexact way of accounting for the time discrepancy. What’s more, to quote Jerry in such a case, I must trust Jerry’s recollection — but our memories are notoriously unreliable. What we say can melt from memory faster than an ice cube left in the midday sun.

So, strictly speaking, my lines count as nonfiction only if you accept my functional and stylistic tweaks…and if you tolerate the shift in the timeline…and if you trust that Jerry’s recollection is consistent with how he truly felt all those years earlier.

We weren’t there when Babe Ruth kept hitting or Rosa Parks kept sitting or Betsy Ross allegedly got to sewing. And sometimes the star of a particular true story did not record his or her take for posterity. In cases like that, we must turn to those who were closest to the action, if possible. History is written not only by the winners but also by the witnesses — people who were not famous and who probably never dreamed they’d be quoted in the future. (If only more of them had kept journals — and more of the journals that were kept had survived.)

While any given action can be described in any number of equally passable ways, there’s only one way to accurately transcribe someone’s spoken words. Best-case scenario: it’s done immediately after the words were spoken. And even then it may be a word or two off, even if the speaker himself is the one transcribing — and even if it’s recorded electronically. Did Neil Armstrong say “one small step for man” or “one small step for a man”? Millions were listening, yet the debate has raged for nearly five decades.

When writing nonfiction, my goal is to let my subjects speak for themselves to whatever extent possible and to source every statement — practically every sigh — mercilessly. Pure nonfiction may be unattainable, but writers owe it to readers to come as close as possible.

From the May/June 2013 issue of The Horn Book Magazine.

RELATED

RECOMMENDED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!

Mary

Thanks for a thoughtful article, Marc. It's great to hear about the process you went through in making the decisions you did for BOYS OF STEAL. I am inclined to agree with you and the choices you made.Posted : May 01, 2013 04:38