Coretta Scott King Author Award Acceptance

This morning, I would like to talk to you about black men.

This morning, I would like to talk to you about black men. Let’s

face it: as an African American woman, it is perhaps unlikely that

I have authored a book and am speaking on behalf of black men.

But here I am.

This morning, I would like to talk to you about black men. Let’s

face it: as an African American woman, it is perhaps unlikely that

I have authored a book and am speaking on behalf of black men.

But here I am.So, to begin, I’d like to share the story of a man whose hands were both mighty and gentle. He was the first black man I ever met. A man I called Daddy.

From the moment I came into this world, I was greeted by my father’s strong, loving hands. When I was less than a minute old, my father used those hands to hold me close, and to promise me that my childhood and my life would be very different from his own.

Just days before I was born in Washington DC, and just a few blocks away from the hospital where my parents welcomed me, Daddy had walked, hand in hand, with his fellow protesters at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. With his first child on the way, Daddy clung to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s dream — that someday all children, including his own, would be judged by the content of their character.

Martin’s words were like a golden ribbon swirling through that hot August sky. And there was my father among 250,000 fellow dreamers — reaching up with both hands to touch a piece of Martin’s golden dream. With a faith so powerful, my father held fast to that vision — that all of us would realize the words of the Negro spiritual that is a shining beacon at the end of Dr. King’s “I Have a Dream” speech. Mama and Daddy hoped against hope that their children would be “free at last.”

As soon as I took my first infant’s breath, my parents swaddled me with Dr. King’s golden dream. As I grew, I would come to find out that when Daddy was born, his own father’s hands were nowhere close. His father’s hands, the hands of my grandfather, were in a faraway city, working as a janitor, elevator operator, domestic servant, sanitation engineer — laboring at any job he could find to support a family of five children. And as my grandfather’s callused hands worked and worked, earning just a few dollars each month, he believed deeply in equality’s dream. A dream he would bestow upon his sons and daughters.

His own father, my great-grandfather, was born soon after slavery ended. As a young boy, his hands worked brittle land and reached for a better tomorrow. He also held fast to the far-off dream of “free at last.”

It is because of this Davis legacy of men who had perseverance, determination, and faith in a dream, that I am able to stand here this morning to celebrate black men who changed America.

My father is passed away now. But as a creator of nonfiction, I am committed to facts. And I know for a fact that Daddy and Grandpa and my great-grandfather are together — hand in hand — looking down on this scene, rejoicing.

Now, I’d like to fast-forward to more black men. Those of modern times. Those whose hands are doing great things in the wake of Dr. King’s dream of equality.

I’ll start with my brother, Phil. He and I had grown weary of so much bad press and ignorant stereotyping of black males. As my brother’s older sister, and as the mother of a black son, and the wife of a black man, I’d become acutely aware of the negative impact this bad press and these stereotypes have—especially on boys who are developing an image of what it means to be a black man coming of age. Even in its subtlest forms, this negativity stitches a corrosive thread into a child’s psyche and makes him think he’s inferior. Once this belief is established, it’s hard to turn it around.

So there was Phil, reading the newspaper day after day, seeing the news reports night after night. He questioned why — when he and I, and our sister, Lynne, had grown up in a home of hope and positivity as it related to black manhood — when it came to black men as depicted in the media, there often seemed to be bad news. And so my brother stuck it to me. “You’re a writer,” he said. “Make a book that tells the real story.”

It was around this time that my teenage son, Dobbin, also started to notice the nightly news. The bad press. The false information about black men. And again, as my son was approaching manhood, I started to see the negative impact stereotypes and profiling create.

I have always told both my children — my daughter and my son — it is good to be truthful. And one day I heard myself saying, “Dobbin, all that mess you read about black men is a lie. It is false. Not true.”

“Son,” I said, “People will tell you, you can’t, you won’t, you must not try. Some will even insist that a book in your hand makes you less of a black man.”

So when the request came from my son — “Mom, write a book about the goodness of black men. Give me nonfiction that’s the real deal — and fun for me to read!” — I eagerly accepted the invitation. I said, “Dobbin, about that bad stuff you read and see on TV, Mama’s gonna set the record straight. In a book. Especially for you.” I felt an overwhelming urgency to create a testament to the positivity of African American manhood, as told through the biographies of men who shaped racial progress in the United States.

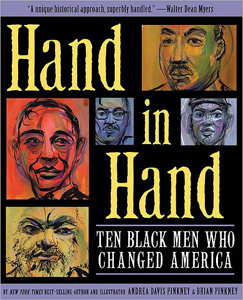

That’s when a very special black man came into the picture: Brian Pinkney, my husband of twenty-one years, who, as a gift to our son, started to render a series of exquisite portraits of our nation’s most notable African Americans, from Benjamin Banneker to Frederick Douglass to Booker T. Washington. From W.E.B. DuBois and A. Philip Randolph to Thurgood Marshall and Jackie Robinson. From Malcolm X to Martin Luther King Jr. and, of course, our first black president, Barack H. Obama II.

Inspired by Brian’s bold, expressive portraiture, I dove headlong into research, culling facts from primary source material, interviews, documents, and my own family tree. One of the recurring themes I found in each man’s story was the importance of books, reading, writing, expressing oneself through public speaking, and finding hope and redemption through education.

It then occurred to me that a book doesn’t care who reads it. Once a black man who was enslaved opened a book, he had crossed over into a “free state.” And while it may have been illegal or discouraged for these men to read, once they seized the power of literacy, they had entered a “promised land,” and there was no turning back.

Each of the men in Hand in Hand gained the power to change America through reading and writing. No matter the era a particular man was born into, once he got his hands on a book, thank God Almighty — his mind, heart, and soul could be free at last!

Also, with the men I had researched, there was never a question of if they could succeed. Each of the men had very solid ideas about what they would accomplish when they reached their goals.

In my research, I also discovered recurring affirmations about black men that I wanted to convey to Dobbin through the men’s stories. “Child,” I said, “you already know these facts, but my book will shine a light on the following truths:

Black men are builders.

Black men unify — and are unified.

Black men love to read.

Black men have ambitions, and the backbone to carry them out.

Black men are powerful public speakers, charismatic, smart, skilled writers, and effective communicators.

Black men are astute listeners. They respect themselves and others and place family values in high regard.

Black men have good manners.

Black men are spiritual.

And, honey, black men are among the most beautiful creatures on God’s planet.”

As I researched and wrote, to my son and brother and husband, I said, “It’s time to celebrate your beauty. Your brains. Your bravery. The moment has come to rejoice in the tremendous horizon of possibility that is available to you.”

This ignited an important question. How many men, and which men, should be included in a book that could be called “A Hundred Black Men Who Changed America”?

My initial list was a very long one. There are so many black men who have made a tremendous impact on progress in America. Narrowing the list was not easy. It was important to span history, from the colonial period, to the Civil War, to the turn of the twentieth century, World War I, the Great Depression, the civil rights movement, and modern day. I found it essential to include men from a variety of sectors. And, rather than simply presenting a snapshot of each, I wanted to be able to delve into the early lives, influences, and motivations that led to the accomplishments of the men in the collection. I was eager to explore the humanity that makes each man unique. Keeping the list to ten allowed me to do this. Through my research, conversations with scholars, kids, uncles, brothers, cousins, and mothers, several names kept emerging. The men who appear in Hand in Hand are those who made the cut.

Also, as I uncovered more and more information about the men I planned to include, the narrative and thematic approach for the book emerged — the importance of each man’s hands, and how these hands built our nation.

Thus, the volume is composed of ten distinct stories. When put together like a chain, the individual accomplishments of these men link up to tell one story. A story of triumph that my son, brother, and husband can be proud of.

The Hand in Hand narratives begin with a praise poem that celebrates the power of each man’s hands. One of my favorites is the chapter-opener for baseball great Jackie Robinson:

His hands crossed the color line.

When he heard the call, “Play ball!”

he reached to the other side,

where he raced

’round the Dodgers’ all-white diamond.

Stirred up second base.

Sent dirt’s dust rising

while he slid

to the plate.

Brought baseball’s new inning.

Bat held high.

Turning the other cheek.

Swinging righty.

Black-pride slugger

Number 42

Stealing home.

Make no mistake—

“Safe!”

I chose to begin each Hand in Hand chapter with these praise poems because I believe that our hands are very powerful.

I believe our hands can lift even the heaviest weight of discouragement.

I believe our hands can clap out a celebration song whose mighty rhythms call us forward to serve the highest good.

As I said, I’m a creator of nonfiction. I like facts. So, in addition to believing, I know for a fact that when I put my hand in yours, together we can do what we could never do alone.

Whether those hands are the hands of ten black men.

Or the hands of my very own father holding up a ribbon of hope for his newborn daughter.

Or the hands of this black mother embracing her son by writing a book that is a mirror of his emergence into manhood.

I believe that when joined together, the hands of each and every one of us in this room have the power to change not only America but our entire world.

In closing, I’d like to express some very important thank yous. I wish to thank Dorothy Guthrie and the Coretta Scott King Book Awards committee for your hard work, and for using your hands to give books to children that reflect their splendor. Thank you, too, for making a cold day last January a lot warmer by calling to let me know that Hand in Hand had been selected to receive the 2013 Coretta Scott King Author Award. If you have ever seen a grownup do a cartwheel of joy on the sidewalks of New York City, that was me on January 28, 2013.

Thank you to my brilliant and tireless editor, Stephanie Owens Lurie, who with sure-handed skill, ingenuity, and smarts, took Hand in Hand from a kernel of an idea to the book we now hold. Designer Whitney Manger and art director Joann Hill, your hands brought creativity and beauty to the design of this book. Dina Sherman and Lizzy Mason, you are a dream marketing and publicity team. Thank you for getting Hand in Hand into people’s hands.

Rebecca Sherman, my agent at Writers House, my gratitude to you for your guiding hands, grace, and intelligence, that always point me in the right direction.

Thank you, Mr. Walter Dean Myers, whose hands are definitely changing America and who, amidst his duties as the National Ambassador for Young People’s Literature, was gracious enough to read and vet the manuscript for Hand in Hand and to offer several helpful editorial suggestions, all of which we took.

Thank you to my brother, Phil, and my son, Dobbin, whose collective prodding sparked the creation of Hand in Hand. And whose inspiration is the reason why, when the Horn Book asked each award recipient to suggest a loved one to prepare a profile for the awards issue, there was no question in my mind that I would ask my brother and son to write it. Thank you to the Horn Book for your continued support of the Coretta Scott King Awards and inclusion of the Coretta Scott King Awards speeches.

I’ve spoken a lot this morning about my late father. But I would also like to thank my other father, my “father-in-love” — my “Daddy Lion” — Jerry Pinkney, whose hands are so generous and who always holds me up with his encouragement and goodness.

Because of the power of my father’s devotion to my mother and his three children, and the family example of Jerry and my “mother-in-love,” Gloria, I have experienced what the powerful hands of a black family can do.

And so, when I met a beautiful, strong, and loving black man named Brian Pinkney, I knew his hands would forever hold me. Brian, your hands not only create beauty through your paintings, but also through the love they give as a husband and father. My darling, “thank you” is too small a sentiment to express how much I love you.

To everyone here this morning — right now, this minute, let us all believe that our mighty hands can carry out the dream of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Coretta Scott King’s golden legacy of brotherhood, sisterhood, and peace.

Thank you!

From the July/August 2013 issue of The Horn Book Magazine. Read the loving profile of Andrea Davis Pinkney written by her husband, Brian, her son, Dobbin, and her brother, Phil Davis Jr.

To commemorate Black History Month, we are highlighting a series of articles, speeches, and reviews from The Horn Book archive that are by and/or about African American authors, illustrators, and luminaries in the field — one a day through the month of February, with a roundup on Fridays. Look for the social media tag #HBBlackHistoryMonth17 on Facebook.com/TheHornBook and @HornBook. You can find more resources about social justice and activism at our Talking About Race and Making a Difference resource pages.

RELATED

RECOMMENDED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!