2018 School Spending Survey Report

How to Choose a Goose: What Makes a Good Mother Goose?

It is a truth universally acknowledged that every English-speaking child is the better for an early friendship with “Mother Goose” — early meaning from birth, because nothing boosts language development better than those catchy rhymes and rhythms.

Mother Goose rhymes have appeared in print for more than two hundred years. Since Randolph Caldecott elaborated on verses like “Hey Diddle Diddle” and “Bye Baby Bunting” with his ebullient caricatures of English country life, hundreds of illustrators have adapted the rhymes to their own styles and sensibilities. A few of these collections endure; many more have fallen by the wayside, even such treasures as L. Leslie Brooke’s 1922 Ring O’Roses. Fashions change, as do ideas about what’s acceptable fun or ridicule; perhaps Brooke’s “Crooked Man” and “Simple Simon” were too realistic for comfort, even though they are more affectionate portraits than unkind caricatures. Feodor Rojankovsky’s Humpty Dumpty (in his 1942 Tall Book of Mother Goose) sported a dark forelock and a little black toothbrush of a moustache — a satisfying lampoon of Hitler when it was published, but one deemed a problematic political invasion of the nursery a few years later.

Illustrations for Mother Goose come in several flavors. The most widely accepted are often the sweetest; Kate Greenaway and Jessie Willcox Smith set the tone with their pretty children in the rural, period settings many people associate with nursery rhymes. Blanche Fisher Wright’s enduring 1916 compendium The Real Mother Goose is in this tradition, as are any number of today’s mass market editions. More stimulating to young imaginations is the kind of rambunctious vigor initiated by Caldecott, carried on by Brooke, and adapted with idiosyncratic verve by such luminaries as Roger Duvoisin, Raymond Briggs, Amy Schwartz, and Michael Foreman — vigor that reflects the outlandish characters and shenanigans in the verse itself. Other illustrators make these little dramas more immediate by setting them in the present, as did Rojankovsky (though because his “present” was the 1940s, his illustrations are now in period dress) or Dan Yaccarino in his stylish, urban 2003 Mother Goose.

Illustrations for Mother Goose come in several flavors. The most widely accepted are often the sweetest; Kate Greenaway and Jessie Willcox Smith set the tone with their pretty children in the rural, period settings many people associate with nursery rhymes. Blanche Fisher Wright’s enduring 1916 compendium The Real Mother Goose is in this tradition, as are any number of today’s mass market editions. More stimulating to young imaginations is the kind of rambunctious vigor initiated by Caldecott, carried on by Brooke, and adapted with idiosyncratic verve by such luminaries as Roger Duvoisin, Raymond Briggs, Amy Schwartz, and Michael Foreman — vigor that reflects the outlandish characters and shenanigans in the verse itself. Other illustrators make these little dramas more immediate by setting them in the present, as did Rojankovsky (though because his “present” was the 1940s, his illustrations are now in period dress) or Dan Yaccarino in his stylish, urban 2003 Mother Goose. Editions for different audiences have always appeared in different shapes and sizes, from board books featuring single rhymes to Peter and Iona Opie’s scholarly tomes. Those for the youngest may contain just a few familiar verses, copiously illustrated. Older children can explore fat volumes with hundreds of rhymes, including additional, often omitted verses for well-known rhymes. Smaller volumes may have a particular focus. In To Market! To Market!, Peter Spier set a score of rhymes in the early nineteenth-century market town of New Castle, Delaware. Leonard Marcus and Amy Schwartz celebrate the foolish, the disappointed, and various miscreants in a merry take on Mother Goose’s Little Misfortunes. Tracey Campbell Pearson’s agile pen renders a single rhyme, “A Apple Pie,” into a joyful, action-packed foldout panorama and “Little Bo-Peep” into a winsome board book, its drama recast as a toddler tossing toys from her crib. Robert Sabuda’s virtuoso pop-up, The Movable Mother Goose, features arresting graphic design as well as extraordinary paper engineering. With We Are All in the Dumps with Jack and Guy, Maurice Sendak turns two hitherto unrelated rhymes into a fantasy on urban poverty, social responsibility, and compassion. Versatile Mother Goose provides a rewarding venue for many such creative endeavors.

Editions for different audiences have always appeared in different shapes and sizes, from board books featuring single rhymes to Peter and Iona Opie’s scholarly tomes. Those for the youngest may contain just a few familiar verses, copiously illustrated. Older children can explore fat volumes with hundreds of rhymes, including additional, often omitted verses for well-known rhymes. Smaller volumes may have a particular focus. In To Market! To Market!, Peter Spier set a score of rhymes in the early nineteenth-century market town of New Castle, Delaware. Leonard Marcus and Amy Schwartz celebrate the foolish, the disappointed, and various miscreants in a merry take on Mother Goose’s Little Misfortunes. Tracey Campbell Pearson’s agile pen renders a single rhyme, “A Apple Pie,” into a joyful, action-packed foldout panorama and “Little Bo-Peep” into a winsome board book, its drama recast as a toddler tossing toys from her crib. Robert Sabuda’s virtuoso pop-up, The Movable Mother Goose, features arresting graphic design as well as extraordinary paper engineering. With We Are All in the Dumps with Jack and Guy, Maurice Sendak turns two hitherto unrelated rhymes into a fantasy on urban poverty, social responsibility, and compassion. Versatile Mother Goose provides a rewarding venue for many such creative endeavors.Each of these books is a world unto itself; to enter one is to go to a place both rich and strange, whether pretty and placid or comically offbeat. Mother Goose is read, reread, chanted, and pored over with a special imaginative intensity.

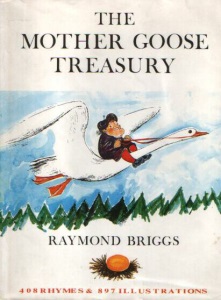

The collection my children almost wore out was The Mother Goose Treasury, illustrated by Raymond Briggs and with “acknowledgements and grateful thanks to Peter and Iona Opie,” as has been de rigueur for the best collections since those eminent folklorists published The Oxford Dictionary of Nursery Rhymes in 1951. Robust, earthy, and sporting more than 400 verses, Briggs’s book features clean, uncluttered pages with lots of spot art; sequenced vignettes for longer dramas; colorful, action-packed full-page art; and a marvelous array of characters — seedy or cranky, feckless or determined, often mischievous, rarely prim. As critic John Rowe Townsend observed in Written for Children, “The world of Raymond Briggs . . . is full-blooded and boisterous. Briggs’s people are notably lacking in any hint of delicacy or sensitivity. They tend to have jutting chins and prominent, if scattered, teeth. In any situation where only the fittest could survive, they would be among the eaters rather than the eaten.”

The collection my children almost wore out was The Mother Goose Treasury, illustrated by Raymond Briggs and with “acknowledgements and grateful thanks to Peter and Iona Opie,” as has been de rigueur for the best collections since those eminent folklorists published The Oxford Dictionary of Nursery Rhymes in 1951. Robust, earthy, and sporting more than 400 verses, Briggs’s book features clean, uncluttered pages with lots of spot art; sequenced vignettes for longer dramas; colorful, action-packed full-page art; and a marvelous array of characters — seedy or cranky, feckless or determined, often mischievous, rarely prim. As critic John Rowe Townsend observed in Written for Children, “The world of Raymond Briggs . . . is full-blooded and boisterous. Briggs’s people are notably lacking in any hint of delicacy or sensitivity. They tend to have jutting chins and prominent, if scattered, teeth. In any situation where only the fittest could survive, they would be among the eaters rather than the eaten.”Now, though, there’s a plethora of Mother Geese in print, Briggs’s isn’t among them. It’s well known that the swing from the verbal to the visual within the last generation has remodeled not only tastes but the very way children perceive. No longer is it acceptable for color to alternate with black and white; children today expect all color, all the time, and are accustomed to a more generous supply of illustrations. Busy parents are content to settle for a relatively brief collection, perhaps supplemented with picture books spun from single verses.

Fortunately, in this new climate, there are still good choices, big and small, sweet or silly or pungent or all three. Iona Opie’s My Very First Mother Goose (along with its companion volume, Here Comes Mother Goose), illustrated by Rosemary Wells, is a lap-friendly charmer, with large type, ample dimensions, and bright colors. Though some characters are human, more are animals, especially cats, mice, and bunnies. “Little Jumping Joan” is a black, rope-skipping rabbit who doubles as the narrator of “I had a little nut tree” — who better to “skip over water, dance over sea”? Mischievous, anxious, earnestly hard-working, gleeful, or affectionately cuddly, these appealing animal characters will be familiar to readers of Wells’s many popular picture books. Also, using them is a tactful way to sidestep the issue of racial balance.

Fortunately, in this new climate, there are still good choices, big and small, sweet or silly or pungent or all three. Iona Opie’s My Very First Mother Goose (along with its companion volume, Here Comes Mother Goose), illustrated by Rosemary Wells, is a lap-friendly charmer, with large type, ample dimensions, and bright colors. Though some characters are human, more are animals, especially cats, mice, and bunnies. “Little Jumping Joan” is a black, rope-skipping rabbit who doubles as the narrator of “I had a little nut tree” — who better to “skip over water, dance over sea”? Mischievous, anxious, earnestly hard-working, gleeful, or affectionately cuddly, these appealing animal characters will be familiar to readers of Wells’s many popular picture books. Also, using them is a tactful way to sidestep the issue of racial balance.An illustrator of Mother Goose has many such choices, each a chance for creative interpretation. For example, Wells’s “brave old duke of York” — a benevolent-looking gent, pajama-clad and portly — watches his toy soldiers march up and down a hill built of fat books. (Observant tots may notice that the march ends in a wastebasket.) The pussycat who said he’d “frightened a little mouse under [the queen’s] chair” is evidently fibbing — it’s the cat who exhibits alarm here, while the mouse, clearly a privileged personage, sticks out her tongue at him. Just about every verse has such nifty details to discover in successive “readings” of the pictures.

With just sixty-eight rhymes, most of them short (or without their final verses), My Very First Mother Goose is a fine place to begin. Eventually, however, the well-read child will need a more comprehensive collection.

Tradition-minded parents may head for Wright’s Real Mother Goose, which has nearly 300 rhymes and clearly drawn characters that recall Kate Greenaway’s pretty children. With rhymes outnumbering illustrations and art that rarely extends the text, it’s a book to acquire for its less familiar verses and old-fashioned flavor.

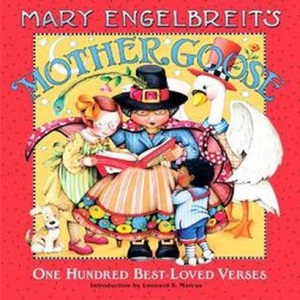

More accessible to today’s children is Mary Engelbreit’s Mother Goose, 100 rhymes visualized in Engelbreit’s old-timey greeting-card style, the round-faced characters reliably cute and pink-cheeked (even the lambs and unicorn). The selections, chosen with the help of critic Leonard Marcus, are excellent, as is his introduction, peppered with such sage insights as “It is one of the happy truths about Mother Goose verses that it is absolutely impossible to sound too foolish while saying them”; and “These days, the first rhymes most children know are those . . . in television commercials. Against this backdrop, wise old Mother Goose holds out a refreshing, life-enhancing alternative: equally irresistible rhymes with nothing to sell.” Wise comments, worth taking to heart.

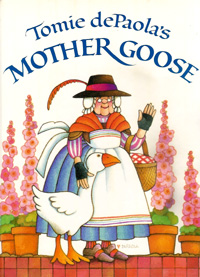

More accessible to today’s children is Mary Engelbreit’s Mother Goose, 100 rhymes visualized in Engelbreit’s old-timey greeting-card style, the round-faced characters reliably cute and pink-cheeked (even the lambs and unicorn). The selections, chosen with the help of critic Leonard Marcus, are excellent, as is his introduction, peppered with such sage insights as “It is one of the happy truths about Mother Goose verses that it is absolutely impossible to sound too foolish while saying them”; and “These days, the first rhymes most children know are those . . . in television commercials. Against this backdrop, wise old Mother Goose holds out a refreshing, life-enhancing alternative: equally irresistible rhymes with nothing to sell.” Wise comments, worth taking to heart. Two of the best of the more comprehensive volumes still in print came out in the 1980s. With its quaint, innocent-looking figures and childlike drawing style, Tomie dePaola’s Mother Goose (with 204 rhymes) is immediately appealing. But there’s much more going on in dePaola’s art than the casual reader may notice at first.

Two of the best of the more comprehensive volumes still in print came out in the 1980s. With its quaint, innocent-looking figures and childlike drawing style, Tomie dePaola’s Mother Goose (with 204 rhymes) is immediately appealing. But there’s much more going on in dePaola’s art than the casual reader may notice at first.His figures — so decorative, so comfortably arrayed in their ample white space — are also subtly expressive; his sophisticated juxtapositions of light, bright colors are unexpectedly harmonious; his elegantly balanced compositions include just enough action and detail to inspire young imaginations to fill out the stories for themselves. Arrangement of the rhymes, from an unusual fifteen stanzas about Mother Goose herself to a series of bedtime entries (closing with two prayers), is coherent. All in all, it’s a book to have early and enjoy through childhood and beyond.

For somewhat older children, The Arnold Lobel Book of Mother Goose (306 rhymes; formerly titled The Random House Mother Goose) is especially rich in variety, story, and visual imagery. Old standards with a full complement of extra verses; variants on the familiar plus much that’s unfamiliar; couplets, riddles, limericks, ballads — all are grouped by subject (rain, say, or chickens), or by more tenuous links, and set to good advantage among a wealth of spot art, spreads, and vignettes. A string of small pictures may narrate a single story or multiple rhymes share a setting (the sea, rooms in a house, the moon). Borders sometimes fence the action, but elsewhere it escapes into large, dramatic vistas. Each freely drawn illustration is neatly self-contained, yet all are marshaled into exquisitely designed spreads. Characters are as lively and varied as all humanity, mostly comic or amiable but sometimes unexpectedly dark (a tiny Wee Willie Winkie issues an urgent warning among towering, angular buildings; the cow sweeps over the moon in an awesome celestial phenomenon). Creative touches abound: the crooked man is a cubist portrait; it’s mice who like “pease porridge cold . . . nine days old”; London Bridge is a vertiginous, patched-together conglomeration. All in all, this is an ample and robust volume, vibrant with the many human conditions that gave rise to the rhymes in the first place: quirks, incongruities, injustices, nightmares, absurdities, laughter, hopes, dreams.

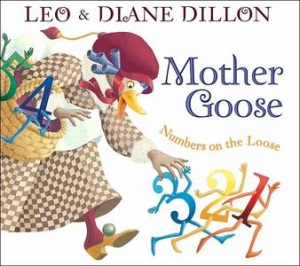

For somewhat older children, The Arnold Lobel Book of Mother Goose (306 rhymes; formerly titled The Random House Mother Goose) is especially rich in variety, story, and visual imagery. Old standards with a full complement of extra verses; variants on the familiar plus much that’s unfamiliar; couplets, riddles, limericks, ballads — all are grouped by subject (rain, say, or chickens), or by more tenuous links, and set to good advantage among a wealth of spot art, spreads, and vignettes. A string of small pictures may narrate a single story or multiple rhymes share a setting (the sea, rooms in a house, the moon). Borders sometimes fence the action, but elsewhere it escapes into large, dramatic vistas. Each freely drawn illustration is neatly self-contained, yet all are marshaled into exquisitely designed spreads. Characters are as lively and varied as all humanity, mostly comic or amiable but sometimes unexpectedly dark (a tiny Wee Willie Winkie issues an urgent warning among towering, angular buildings; the cow sweeps over the moon in an awesome celestial phenomenon). Creative touches abound: the crooked man is a cubist portrait; it’s mice who like “pease porridge cold . . . nine days old”; London Bridge is a vertiginous, patched-together conglomeration. All in all, this is an ample and robust volume, vibrant with the many human conditions that gave rise to the rhymes in the first place: quirks, incongruities, injustices, nightmares, absurdities, laughter, hopes, dreams. There’s always room for another fresh take on the old favorites. In Leo and Diane Dillon’s new Mother Goose Numbers on the Loose, the gifted illustrators bring twenty-four rhymes to life in richly detailed mini-stories of their own invention. Like many a Mother Goose, it’s a book for multiple ages: for preschoolers who enjoy the dancing rhymes and rhythms; for primary-age children learning their numbers; and for the older ones, who can appreciate and weave together the many imaginative pictorial details to tell the old stories anew.

There’s always room for another fresh take on the old favorites. In Leo and Diane Dillon’s new Mother Goose Numbers on the Loose, the gifted illustrators bring twenty-four rhymes to life in richly detailed mini-stories of their own invention. Like many a Mother Goose, it’s a book for multiple ages: for preschoolers who enjoy the dancing rhymes and rhythms; for primary-age children learning their numbers; and for the older ones, who can appreciate and weave together the many imaginative pictorial details to tell the old stories anew.So how do we choose — for the new baby, for the avid reader, for the library? As to illustrations, they should create an intriguing world, one to lure a child again and again. For the littlest, it’s important to have durable pages, open format, clarity of design, and a preponderance of familiar verses to revisit until, ineluctably, they’re learned by heart. As Caldecott discovered, these funny, often enigmatic verses beg for visual elaboration. Look for illustrators who’ve made the best of their opportunities. Comparing the illustrations for a favorite rhyme in several collections is a good way to get to know different illustrators, to evaluate their styles, skills, and imaginative strengths and discover which ones suit you best.

A more comprehensive collection can be a treasure house of well-honed verse for the avid reader or reader-aloud: a grand assemblage of thumbnail portraits and delicious nonsense, the lyrical and the raucous, sorrow and glee, the witty, the tragic, or — intriguingly — both at once. Tampering with texts is usually a bad thing, though there are exceptions, as those who remember the earlier version of “Eeny, meeny, miny, mo” will acknowledge. If there’s much that’s unfamiliar, a note on sources shows good faith on the part of the compiler. It’s also helpful to have an introduction, one such as Iona Opie provides for My Very First Mother Goose. Hers is an inspirational celebration, concluding with a playful alphabet of attributes. And who better than Opie herself to give us these last words, some of them as absurd as Mother Goose herself.

Mother Goose will show newcomers to this world how astonishing, beautiful, capricious, dancy, eccentric, funny, goluptious, haphazard, intertwingled, joyous, kindly, loving, melodious, naughty, outrageous, pomsidillious, querimonious, romantic, silly, tremendous, unexpected, vertiginous, wonderful, x-citing, yo-heave-ho-ish, and zany it is.

Just so does Mother Goose continue to engage those tiny “newcomers.”

Titles Discussed Above

Raymond Briggs The Mother Goose Treasury; illus. by the author (Coward, 1966)

L. Leslie Brooke Ring O’Roses; illus. by the author (Warne, 1922); o.p.

Tomie dePaola Tomie dePaola’s Mother Goose; illus. by the author (Putnam, 1985)

Leo Dillon and Diane Dillon Mother Goose Numbers on the Loose; illus. by the authors (Harcourt, 2007)

Mary Engelbreit Mary Engelbreit’s Mother Goose; illus. by the author (HarperCollins, 2005)

Arnold Lobel The Arnold Lobel Book of Mother Goose; illus. by the author (Random, 1986)

Leonard Marcus Mother Goose’s Little Misfortunes; illus. by Amy Schwartz (Simon, 1990)

Iona Opie Here Comes Mother Goose; illus. by Rosemary Wells (Candlewick, 1999)

Iona Opie My Very First Mother Goose; illus. by Rosemary Wells (Candlewick, 1996)

Tracey Campbell Pearson A Apple Pie; illus. by the author (Dial, 1986)

Tracey Campbell Pearson Little Bo-Peep; illus. by the author (Farrar, 2004)

Feodor Rojankovsky The Tall Book of Mother Goose; illus. by the author (Harper, 1942)

Robert Sabuda The Movable Mother Goose; illus. by the author (Simon, 1999)

Maurice Sendak We Are All in the Dumps with Jack and Guy; illus. by the author (di Capua/ HarperCollins, 1993)

Peter Spier To Market! To Market!; illus. by the author (Doubleday, 1967)

Blanche Fisher Wright The Real Mother Goose; illus. by the author (Macmillan, 1916)

Dan Yaccarino Mother Goose; illus. by the author (Golden, 2003)

From the January/February 2008 issue of The Horn Book Magazine.

RELATED

RECOMMENDED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!