Five questions for Marilyn Singer

Marilyn Singer had already demonstrated considerable versatility of poetic talents when in 2010 she debuted a new verse form in Mirror Mirror: A Book of Reversible Verse (6–10 years, Dutton).

Photo: Laurie Gaboard, The Litchfield County Times

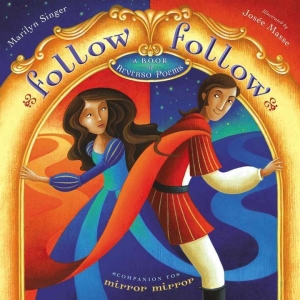

Photo: Laurie Gaboard, The Litchfield County TimesMarilyn Singer had already demonstrated considerable versatility of poetic talents when in 2010 she debuted a new verse form in Mirror Mirror: A Book of Reversible Verse (6–10 years, Dutton). This year she is back with a companion, Follow Follow: A Book of Reverso Poems (6–10 years, Dial; both books illustrated by Josée Masse), in which another cast of folkloric characters get the “reverso” treatment.

1. You invented this verse form and named it. How did you come up with the name?

MS: A reverso is made up of two poems. You read the first down and it says one thing. When you reverse the order of the lines for the second poem, changing only punctuation and capitalization, it says something else. It has to say something different; otherwise it’s what one kid called a “same-o.” When I first started writing these poems, my friend Amy called them “up-and-down poems.” I liked that, but it was a bit of a mouthful. I wanted to use the word reverse, and my husband Steve Aronson, who is one smart cookie, said, “You need something Italianate. How about ‘reverso’?” He gets credit for the name.

2. Do you think folk literature has a particular susceptibility to this poetic form?

MS: At first I didn’t stick exclusively to folk literature. But many of the poems were based on fairy tales, so when I showed that initial batch to an esteemed editor, she suggested I base the entire collection on fairy tales. That struck me as a great idea because fairy tales have strong narratives, and I felt that I could find two sides to one character, or two points in time for that character (such as Cinderella before and at the ball), or two different characters, perhaps with opposing points of view. So far, I’ve written two books of fairy-tale reversos — Mirror Mirror and Follow Follow — and I’m planning to do a third volume based on Greek myths.

However, I don’t think that folk literature is the only possible genre that translates well into reversos. The main thing, really, is to be able to present two sides of someone or something. My forthcoming book, Rutherford B., Who Was He?: Poems About Our Presidents (Disney-Hyperion; illus. by John Hendrix), includes a reverso about a man who viewed himself quite differently from the way the press and public did: Richard Nixon.

3. What was the most difficult poem to write in Follow Follow? And what folktale left you defeated?

3. What was the most difficult poem to write in Follow Follow? And what folktale left you defeated?MS: Oy, a number of them were difficult. I recall several failed attempts at the title poem, “Follow Follow,” about the Pied Piper. The one about the goose that laid the golden eggs was also tricky. One tale I could not turn into a reverso was “The Fisherman and His Wife.” I couldn’t flip either the husband’s or the wife’s voice into that of the fish.

4. What is the most challenging verse form you’ve attempted to write?

MS: Villanelles are tough, but I was able to write one about flamingos in A Strange Place to Call Home: The World’s Most Dangerous Habitats & the Animals That Call Them Home (Chronicle). Sonnets are also challenging, but I’ve done a few of those as well, including one about mountain goats (in the same book). I have never attempted a sestina — and I may never attempt a sestina. And then there are those darn reversos…

5. Do I sing the book’s title to the tune of “Follow the Yellow Brick Road” or “Try to Remember”?

MS: Well, would you rather sound like a Munchkin or El Gallo? I don’t suggest trying it to Crispian St. Peters’s “The Pied Piper.”

Actually, it took longer to come up with the book’s title than to write the actual poems. The Pied Piper poem originally had a different name, but when we (my editor, the publisher, the marketing department, etc.) all agreed on Follow Follow as the title of the book, it also became the name of the poem. And since it’s a “follow-up” to Mirror Mirror, I think it works, don’t you?

From the April 2013 issue of Notes from the Horn Book.

says

says

says

Add Comment :-

RELATED

RECOMMENDED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.