2018 School Spending Survey Report

The Arrival: Author/Illustrator Shaun Tan's 2008 BGHB Special Citation Speech

by Shaun Tan

What a fantastic honor to have won a Boston Globe–Horn Book Award and to be in such good company: not only of book creators whose work I love and have been inspired by, but also of avid librarians, readers, editors, teachers, and all those other good book people.

by Shaun Tan

What a fantastic honor to have won a Boston Globe–Horn Book Award and to be in such good company: not only of book creators whose work I love and have been inspired by, but also of avid librarians, readers, editors, teachers, and all those other good book people. One of my early discoveries as a freelance illustrator, folio in hand, unemployed and clueless, was that the world of children’s literature was filled with so many friendly, welcoming, witty people fascinated by wild, crazy ideas; people for whom playfulness is actually a profession.

What a fantastic honor to have won a Boston Globe–Horn Book Award and to be in such good company: not only of book creators whose work I love and have been inspired by, but also of avid librarians, readers, editors, teachers, and all those other good book people. One of my early discoveries as a freelance illustrator, folio in hand, unemployed and clueless, was that the world of children’s literature was filled with so many friendly, welcoming, witty people fascinated by wild, crazy ideas; people for whom playfulness is actually a profession.I realized too that this was not just the case in Perth, my very remote hometown, but also in Melbourne, Sydney, and — as it turns out — the United States and other places. It’s a cliché to note a global community but still true: here is an international, multilingual country built on stories and daydreams, inclusive of both big and small people, of writers and illustrators, open to both the profound and absurd. We might give each other a coded nod as we pass in airport terminals.

It’s quite appropriate to be receiving an award for this particular book in a city that to me is foreign, in a country I know of mostly through secondhand images and creative imaginings; films, books, TV, and all the stuff of a suburban childhood on the edge of the Indian Ocean. The Arrival is a wordless story about a man who could be anyone, traveling to a place that could be anywhere. This was my simple idea starting out, though the story itself is nothing new, rather an interpretation of many other stories of immigration, especially firsthand accounts from the past two centuries of people coming to Australia and the United States. Both countries are linked by a strong, complex immigrant heritage, one that ripples into the future while, elsewhere, thousands of old photographs oxidize quietly in forgotten albums, moths eat postcards, and bones become soil. Those ripples are of course us: our bodies, languages, beliefs, and aspirations, our sense of belonging, a shared memory that is part fact and part fiction, as is the nature of memory. Perhaps we can see some distant, dreamlike projection of unmet ancestors, and alternative lives, through something as simple as an illustrated book. More importantly, we might also see it in the faces of new visitors — some familiar and some not — who will be stepping onto our shores tomorrow, while others depart for new lives in other places. Elsewhere, other worlds are crumbling; history equivocates between promise and despair. If books do anything well it is that they remind us of what we already know but are inclined to take for granted. They allow us to revisit a library of personal feelings, like a deck of cards reshuffled and laid out on the table in an unfamiliar order. All the parts we know — or at least we think we know. Or at least we try to know.

I personally have little firsthand experience of immigration, which is one reason I find it fertile ground for a new investigation. Most of the images in The Arrival take their cue from images such as those collected in the archives of Ellis Island: photographs of anonymous, bewildered people, often with very little money or education, dwarfed by an enormous, strange statue in a harbor. In a museum, you might see an old picture of someone boarding a train for an unknown place that is going to be their future home; its name is clearly written but has no meaning. And who’s to say that, by some roll of the cosmic dice, this person is not you or me? Old pictures are fascinating that way.

Of course, there are a lot of different immigrant experiences, both positive and negative. There are different reasons for leaving and arriving, and an even greater variety of problems faced at all levels of existence, from buying a bus ticket to raising a family — or indeed rescuing one. I suppose this is what interested me: the immigrant experience seems to contain every variety of emotional, intellectual, and spiritual challenge likely to happen to a human being; everything is called into question. The strangeness of it also touches on the central mystery of anyone’s life, like some basic existential questions from the blurry dawn of childhood: Who am I? Why am I me and not you? How did I happen to be here? And how big is this place anyway?

As readers we are always immigrating, stepping into the shoes of strangers to test our empathy and understanding. That’s pretty good practice for the real world, which is a confronting place full of good and bad things and a lot in between that’s ambiguous: we need an inquisitive imagination to figure it out, something children know intuitively. Too often as adults we are lulled in thinking that our world is “normal,” “ordinary,” “sensible,” or “just so” — and many stand to profit from making us think this. Books are one light against that possible darkness. They transcend our normal expectations, not upwards but sideways, even tunneling underground. They remind us that this is just one world among several thousand possibilities, existing both inside and outside of our heads. There is no “normal” or “just so.”

The Arrival is only one story, and more or less unfinished. Children in a classroom I visited in New York were adamant that the book was about New York City. My elderly neighbors in Melbourne know that it is really about Italian and Greek postwar migration; my dad knows that it is about his own arrival in Western Australia, and his parents’ journey from China to Malaysia; my mum can see elements of her English and Irish background; my fiancée will recognize her separation from Finland. Of course, the book is really about Boston, circa 2008, but that’s just between you and me.

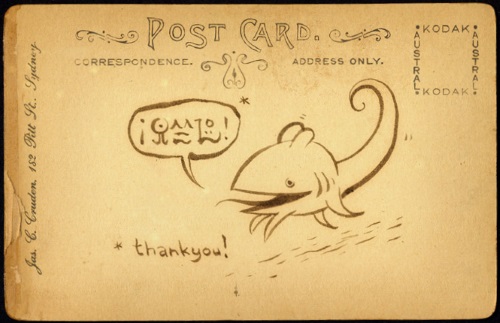

There are many people to thank; like most books, this one had a long journey. It was originally published by Lothian Books in Australia, edited by Helen Chamberlin, whom I’ve had the pleasure to work with for many years. She is very patient, which is a blessing considering how many deadlines I “revised,” spaced out generously over five years. During that time, I had the good fortune to discuss the project with a charming editor at Arthur A. Levine Books (who perhaps won a raffle to pick the company name) and have come to know some excellent new friends at Scholastic in New York. The Arrival is my sixth picture book, but the first to be published in the United States, and I’ve been overwhelmed by the response. I was always concerned when wrestling with the book that it might be too obscure or unreadable, or at least difficult to shelve and market. I was often asked questions along the lines of “Who is this for?” The answer has invariably come from energetic librarians, teachers, booksellers, critics, academics — and even award judges — all those people dedicated to putting books in the hands of the most appreciative readers, building networks of discussion, challenging preconceptions, and bridging the circuit between silent stories and the audience that breathes life back into them. The Horn Book is one great example of that shared passion; these awards are another. Thank you all for your curiosity, commitment, hard work, and encouragement, and my best wishes from one imaginary country to another.

From the January/February 2009 issue of The Horn Book Magazine.

RECOMMENDED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!