Publishers’ Preview: Diverse Voices Redux: Five Questions for Cynthia Kadohata

This interview originally appeared in the May/June 2019 Horn Book Magazine as part of the Publishers’ Previews: Diverse Voices Redux, an advertising supplement that allows participating publishers a chance to each highlight a book from its current list.

This interview originally appeared in the May/June 2019 Horn Book Magazine as part of the Publishers’ Previews: Diverse Voices Redux, an advertising supplement that allows participating publishers a chance to each highlight a book from its current list. They choose the books; we ask the questions.

Sponsored by![]()

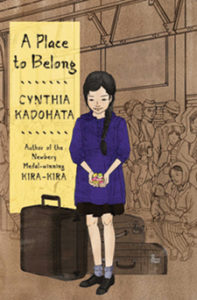

After Hanako’s family is released from the Tule Lake internment camp, her embittered father decides the family will return to Japan, to the Hiroshima countryside. Will Hanako find A Place to Belong?

1. The WWII incarceration of Japanese Americans (and Japanese Canadians) has inspired many great books. Do you have a touchstone among them?

1. The WWII incarceration of Japanese Americans (and Japanese Canadians) has inspired many great books. Do you have a touchstone among them?Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston and James D. Houston’s Farewell to Manzanar and John Okada’s No-No Boy were trailblazing books. Everyone who has written about the camps after those two authors walks in their wake. My dad was a tenant farmer when he was a child, and after I read Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, about white tenant farmers during the Great Depression, I felt almost desperate to know more about my parents’ lives. That led to a desire to learn about my father’s experience of being incarcerated in Poston.

2. What do you think is the hardest thing for a newcomer to Japan to understand?

Even if you have a perfect accent, even if you think you look the same, you don’t necessarily fit in. I think you have to come from that specific culture from a young age. You can love the culture, and love to be there, but belonging is something else.

3. How was the experience of writing A Place to Belong different from that of writing Weedflower, rooted in the same historical events?

3. How was the experience of writing A Place to Belong different from that of writing Weedflower, rooted in the same historical events?People were more reluctant to be interviewed for A Place to Belong. There’s animosity, to this day, toward no-no boys. Some did want to talk about it, but others felt there was a stigma to having renounced. I love the renunciants I interviewed. And I love those who chose to serve instead. My heart breaks for all of them.

4. What messages can resonate today?

The current environment and the past overlay each other in particular on the issues of where one belongs, what makes one American, and deportation. I think (hope!) we all agree that there are absolute moral truths, absolute rights and wrongs. What we don’t seem to agree on is that two decent people can believe different things. That was true of those two factions — renunciants and servicemen — and it is true today as well.

5. Do you imagine what happens to Hanako after the close of the book?

One woman I interviewed went to live in the Hiroshima countryside with her grandparents, and her salient memory of those years is being surrounded by love. She eventually became a doctor after returning to the U.S. I like to think Hanako could be this woman.

Sponsored by![]()

RELATED

RECOMMENDED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy: