Peter Says Please

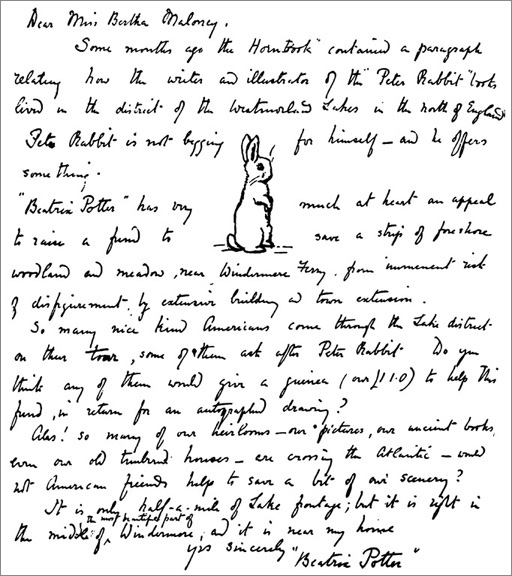

In August 1927 the Horn Book carried an appeal for help in preserving the Lake District countryside in the names of two eminent English countryfolk, Peter Rabbit and Beatrix Potter. In the illustrated letter, Peter pleads mutely, like a dog begging for a bone. But they do not come empty-handed, says Potter, offering a signed drawing in return for a modest, one-guinea (five-dollar) contribution toward preserving land “near my home.” Americans, Potter knew, had a great fondness for Peter and his friends, and a decided weakness for antiquities.

They also took her work seriously. The long, close relationship between Potter and the Horn Book began with a request for background information from Horn Book editor Bertha Mahony to use in the projected reading guide, Realms of Gold. One question perturbed Potter: what were the sources of the Peter Rabbit books? Who was this Bertha Mahony, and what kind of question was that? Reassured by reading recent issues of the Horn Book — Britain had nothing like it — she seized the opportunity to speak her mind. In a long letter that Mahony excerpted for Realms of Gold and later printed almost in full in the Horn Book, under the title “‘Roots’ of the Peter Rabbit Tales,” Potter traces her work — with casual incongruities — to matter-of-fact Nonconformist ancestors, childhood summers in the company of Scottish witches and fairies, and a precocious memory for places and feelings. The “save our homelands” letter followed in short order.

Beatrix Potter's 1927 letter to Bertha Mahony

Beatrix Potter's 1927 letter to Bertha Mahony

With the letter came, lippety, lippety, the five-dollar watercolors — fifty in all, copied from four Peter Rabbit illustrations — to be displayed and distributed at Boston’s Bookshop for Boys and Girls, home of the Horn Book and home ground for friends and admirers of Potter. (One of the scenes, reproduced in the August issue in black-and-white, reappears in color as the frontispiece of Realms of Gold.) Untold admirers apart, the artist’s personal friends on this side of the Atlantic were sufficiently numerous in the late 1920s to warrant the label “Potter’s Americans,” and together they renewed her interest in writing and publishing books.

She was already an immortal. In the twelve years after publication of The Tale of Peter Rabbit — privately in 1901, commercially in 1902 — Potter produced a book or two a year: The Tailor of Gloucester, Squirrel Nutkin, Benjamin Bunny, Two Bad Mice, Tom Kitten, Jemima Puddle-Duck, The Roly-Poly Pudding, The Flopsy Bunnies . . . in nineteen little books, a whole nursery library. Many were set in and around Sawrey, in the Lake District, where Potter bought property after property as her royalties mounted and she was able, belatedly, to break free of her parents and the strictures of polite London society. The Tale of Pigling Bland, the 1913 romance of an earnest white pig and a carefree black pig, is the last of the Lakeland animal tales. That year, at forty-seven, Potter married William Heelis, a local solicitor, and became the model of an all-competent English countrywoman.

A view of Beatrix Potter’s most personal properties in and around the village of Sawrey, in the southern Lake District. The adventures of Tom Kitten, Jemima Puddle-Duck, and others take place on the paths and slopes of Hill Top Farm (1) and at Hill Top Farm House itself (2), which is now a museum. Ginger and Pickles’ shop was right in the village (3). Beatrix Potter Heelis and her husband lived at Castle Cottage (4). During her lifetime Herdwick sheep would likely have been grazing on the hillsides.

A view of Beatrix Potter’s most personal properties in and around the village of Sawrey, in the southern Lake District. The adventures of Tom Kitten, Jemima Puddle-Duck, and others take place on the paths and slopes of Hill Top Farm (1) and at Hill Top Farm House itself (2), which is now a museum. Ginger and Pickles’ shop was right in the village (3). Beatrix Potter Heelis and her husband lived at Castle Cottage (4). During her lifetime Herdwick sheep would likely have been grazing on the hillsides.

To Warne, her long-time publisher, she was almost a lost cause — seldom producing a book, keeping very much to herself. Or so Anne Carroll Moore was advised on a London stopover in 1921. Moore, undaunted, had just visited children’s libraries in postwar France and ordered fifty copies of the brand-new French editions of Peter Rabbit and Benjamin Bunny for them; wouldn’t Potter like to hear more? The luncheon visit turned into an overnight stay and a lifelong friendship. Potter was impressed with Moore’s role at the New York Public Library, unparalleled in Britain, and vastly pleased that Moore, too, considered the disregarded, worst-selling Tailor of Gloucester her finest work. At Moore’s urging she put some leftover verses and drawings — choice leftovers, many of them — into a new book for Christmas 1922, Cecily Parsley’s Nursery Rhymes. It was an incentive to be a cultural icon instead of a business property or the Bunny Lady.

That same summer of 1921, other interested Americans began to find their way to Sawrey, to have tea with Mr. and Mrs. Heelis at Castle Cottage, to look in at Hill Top Farm House, scene of celebrated animal-tale shenanigans, and to take home a drawing as a remembrance. Some had professional connections with children’s books, some didn’t. Some included children, some didn’t. Potter, a forceful woman who was famously, confessedly shy, testified that they “brought me out of myself.” The matter-of-fact farmer, one might also say, was still at-home to the Scottish fairies.

Young Henry P. Coolidge was proof of that. A boy who “didn’t miss a thing,” as Potter noted admiringly, he fell upon a cache of fanciful guinea pig drawings and persuaded Potter to make something of them. What she made, with encouragement from Mahony and a contract from an American publisher, was that strange anomaly The Fairy Caravan — too local to the Lake District for the general public, Potter felt, and too “personal” to publish in England. But suitable perhaps for Americans, who appreciated The Tailor of Gloucester and shared her allegiance to fairies!

The Horn Book, reciprocating, made Potter a special charge. In the February 1928 issue Henry P. gave an account of his visit to Sawrey; in November 1930 children’s book editor Helen Dean Fish reported on her visits to Potter and to Eleanor Farjeon. In 1929 the January issue carried the first chapter of the forthcoming Fairy Caravan, the May issue carried Potter’s discussion of her “roots,” the November issue carried a feature review of Fairy Caravan by Alice Jordan, and a brief endorsement under “New Books.” As a living classic, Potter was entitled to full attention.

During World War II, Mr. McGregor’s garden became, in the pages of the Horn Book, the embodiment of imperishable Britain. Potter and Mahony had stepped up their correspondence after Mahony’s marriage, in midlife, to a manufacturer of colonial reproductions. Potter, a passionate antiquer, took a keen interest in his wares. But talk of finishes and finials gave way, increasingly, to talk of Hitler, appeasement, the near-certainty of war. In 1938 Potter wrote: “Unless America backs us, we are done.” In 1940, relieved at signs of American arousal, she adds that she has never doubted “the real distress” of her New England friends. Mahony’s affirmation, her sign of solidarity, was a long, affectionate tribute to Potter, her homelands, and her “beloved books,” putting old themes in a new, endangered context. A Potter essay, a Potter story, extracts from Potter letters, maintained Potter’s presence after her death in late 1943.

And the connection has continued. Jane Crowell Morse’s selection of Potter’s letters to Moore, Mahony, Henry P., and others, Beatrix Potter’s Americans, came out under the Horn Book imprint in 1982. The panoramic photos of Sawrey on the preceding pages were taken in 1987 by Horn Book staffer Lolly Robinson.

As for the fantasy drawing of mice on the cover, that comes from an illustrated rhyming sheet (reproduced in the Morse book) sent to Mahony by Potter; unlike Potter’s other Americans, Mahony never made the pilgrimage to Sawrey. To capture Potter’s spirit, then as now, the books will do.

From the March/April 1999 issue of The Horn Book Magazine

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!

Connie Neumann

Lovely narrative of not only Beatrix Potter's life and classic Peter Rabbit books, but of her affectionate relationships with and for the Americans who admired her work from afar.Posted : Oct 12, 2016 11:25