Pam Muñoz Ryan Talks with Roger

Talks with Roger is a sponsored supplement to our free monthly e-newsletter, Notes from the Horn Book.

Talks with Roger is a sponsored supplement to our free monthly e-newsletter, Notes from the Horn Book. To receive Notes, sign up here.

Sponsored by![]()

Photo: Sean B. Masterson

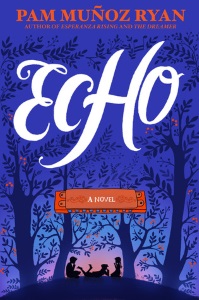

Photo: Sean B. MastersonWhere to start? Echo begins in fairy-tale Germany but swiftly moves to the twentieth century, hopping from the German countryside to Philadelphia to Southern California, all settings tied together by…a harmonica? I called Pam Muñoz Ryan to find out the origin of this unlikely story.

Roger Sutton: Echo is such an ambitious book. What was your point of entry? Where did you start?

Pam Muñoz Ryan: Like with many of my books, I set out to start one book, and along the way I get diverted. I was doing research on the nation's first successful desegregation case, in 1931. It's a little-known case, Roberto Alvarez v. the Board of Trustees of the Lemon Grove School District; people don't know much about it because he won in a lower court, so precedent wasn't set. I was at the historical society in Lemon Grove, which is east of San Diego, with this wonderful docent who was helping me go through all these yearbooks. I came across a picture of a country school from the early 1930s. On the steps are integrated classes of children, and each one of them is holding a harmonica. The docent tried to kind of flip past it, saying, "No, no, that was before the segregation issues," and I said, "Wait, wait, wait, what is that, exactly?" And she said, "Oh, you know, that was our elementary school harmonica band. Everybody had one in the twenties and thirties. You know, during the big harmonica band movement."

RS: Absolutely.

PMR: Of course. Why not? Well, that was just dangling a carrot. I asked her more about it, and she said, "Oh, yeah, if we flip forward, you'll find my brother." I went home and couldn't stop thinking about it. I started doing research and found out that there were over 2500 elementary school harmonica bands in the United States during that time, including Albert N. Hoxie's then-famous Philadelphia Harmonica Band of Wizards. They played for Charles Lindbergh's parade, and for three presidents, and at FDR's inauguration.

I love historical fiction. I don't always write it, but I have a huge affection for it, and when I find some little nugget that's a different angle, or something people don't really know about — especially something as endearing and quirky as a harmonica — I'm really taken with it. Two characters started coming to the fore: a girl in this little country school band, maybe in a school that was integrated and then segregated; and a boy in Hoxie's band — through my research I had discovered that the band was full of orphans. So these two characters, Mike and Ivy, started taking shape, and then I started wondering if the same harmonica could have traveled from one character to the other. And then I wondered who had it before them. In the meantime, I was doing all this research on a particular model of harmonica, the Hohner Marine Band, because it was in both photographs — the picture of Hoxie's band that I found and the one of all the kids in the country school (they're all holding that same model). So then I contacted Hohner in the U.S., and they put me in touch with people in Trossingen, Germany, who run a harmonica museum, and they were just wonderful and gracious. I flew to Germany, and the museum was remarkable. Hohner was a master of marketing, and for every world event, there's a commemorative harmonica.

RS: After reading your book I went to the Hohner website to look at the history of some of their models, and there are some really beautiful pieces.

PMR: It's amazing. The museum was very complete. They have models of what the factory looked like at the time of my book. That's where I learned about the young apprentices who worked there, and about the demise of the six-pointed star engraving. And so the character of Friedrich started taking shape. Now I had these three characters, but I didn't want the book to just be episodic, having a harmonica that just travels from person to person to person. I wanted a richer thread to hold it all together, so that's how I started imagining the harmonica's backstory. These three characters are living through some of the darkest and most challenging times in history. Friedrich is in Nazi Germany, for Mike it's the Great Depression, and Ivy is living through the era of segregation. There was something in me that wanted to give them some beauty and light that would give them the impetus to carry on. Something that lifted their self-esteem, or gave them some sort of strength and confidence.

RS: And then how did you get those three sisters in, in the fairy tale that opens the novel?

RS: And then how did you get those three sisters in, in the fairy tale that opens the novel?PMR: I have always been intrigued by fairy tales. I was one of those obsessive readers as a young girl, very much able to suspend disbelief in whatever I was reading, so I really loved fairy tales. I'd always wanted to write one, but I didn't want to write one just for the sake of it. I wanted it to be organic to whatever it was that I was doing, so I set out to write an original fairy tale where magic became imbued into the harmonica. I studied the genre, and I reread a lot of fairy tales. I also reread Philip Pullman's Fairy Tales from the Brothers Grimm. I love all of his analysis. I think what I love most about fairy tales is that the genre is very different from a novel. In a fairy tale, you tell instead of show. In a novel, you show instead of tell. I had to really adjust my way of thinking, but it was also freeing on some level. I created the fairy tale element so that the harmonica could have the magic it needed, so that each character could feel this euphoric sense of well-being.

RS: Did you write from page one to page six hundred, or were you concentrating on different parts at different times?

PMR: I had started working on it, on some level, before I even went to Trossingen, before I had that third character, so I didn't work on it chronologically. But I did understand the chronology that I wanted in the end.

RS: So you knew you were going to bring two characters together, you just didn't know about the third?

PMR: I knew I needed a third story arc, and I found it when I went to Germany. Once I knew the framework, that it would be three stories framed by a fairy tale, then I was able to begin each story. You have to remember this is six years in the making, so it's hard for me to remember precisely the order. I did work on it in chunks, and of course went back and forth with my editor, but there was so much weaving and reweaving that it's hard to distinguish, especially in the last few years. I am sort of a recursive writer anyway, always going back to the beginning and pulling that thread. I bought a huge seven-foot-long, four-foot-high whiteboard and put it in my office. I wrote the months for each year in which the characters' stories took place, and I had all the leitmotifs—the recurring themes, people, places, and things—in long lists of words and phrases that echoed in each story. Some of them I think the reader will be able to pick out, but many of them I just wanted more on a subconscious level. And then there are these threads of warehousing: in the fairy tale the warehousing of women, in Friedrich's story the warehousing of the Jews, and the warehousing of children in Mike's story, the warehousing of the Japanese and the Mexican Americans in Ivy's story. There were these odd little threads that were woven through the whole book, so it helped me to have this big diagram on the whiteboard, and it helped me to have this visual.

RS: Did I make up the shout-out to Holes?

PMR: You know, you are not the first person to see that. But if I did, it was completely — you mean Louis Sachar's Holes?

RS: Yup. There are peaches.

PMR: What?

RS: You have a jar of peaches in there.

PMR: Oh my god. That is really interesting. I guess as a writer there are so many things you do subconsciously.

RS: Well, I thought of it because you have the same kind of mythic base, and then these braiding stories coming together.

PMR: And I do have that jar of peaches. I didn't do it consciously, though, to be honest.

RS: I think of a book of yours I love, The Dreamer, which is really beautifully contained, kind of gemlike. And now with Echo we have this huge canvas. How was it different to work on?

PMR: Number one, it takes a lot longer. The Dreamer was about one person's life, Pablo Neruda, and it was more linear. This one was just bigger. It's three stories and they needed to have some threads that held them together. Also, because The Dreamer is illustrated, I knew in the back of my mind that Peter Sís was going to say things in his art that I didn't need to say in the book.

RS: It's funny, you keep saying three stories, and I'm thinking about the three stories in the book, but I'm also thinking about the three stories of a house, because they're really built on top of each other.

PMR: Oh, interesting!

RS: The three stories aren't working at the same time. Each one depends upon the one before.

PMR: Right. That's very true. I love that. Whether I ever accomplish it or not, as a writer I want all of that to happen, but I want it to feel organic and integrated. At the end, more than anything, I think my most ardent goal is I want the reader to turn the page.

RS: I remember when Lizette Serrano [from Scholastic] handed the book to me at ALA, and I thought, "Oh, it looks so long." And I started on my diatribe about long books, and Lizette said, "Don't worry. It goes really quickly."

PMR: Did you find that it went quickly?

RS: I did.

PMR: Oh, good. I was happy when I saw the book, because the leading is easy on the eyes, too. There's enough space. It doesn't feel really burdensome.

RS: We old folks bless you.

PMR: Do you want to ask me if I play the harmonica?

RS: Do you play the harmonica?

PMR: I kind of learned how to play some of the songs in the book. It's very easy to do, but I'm not really a musician. I will tell you something interesting that has happened after writing this book. Everywhere I go, I am almost always asked if I still play the cello. It took a long time to figure out why people were asking me that. I think they thought because of how I wrote about the cello music in Friedrich's story that I play the cello.

RS: You're a very accomplished woman. Harmonica, cello, writing.

PMR: Maybe I should say, "Oh, no, I gave that up years ago."

RS: "I gave it up for the harmonica."

PMR: Yes. But I will say this: the wonderful thing about music is you don't have to be a musician to love music, and you don't have to be a writer to love and appreciate books, and you don't have to be an artist to love and dedicate your life to art. That's what I wanted for the story. I wanted that beauty to illuminate my characters' tasks.

Sponsored by![]()

RELATED

RECOMMENDED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy: