One Childhood, One World

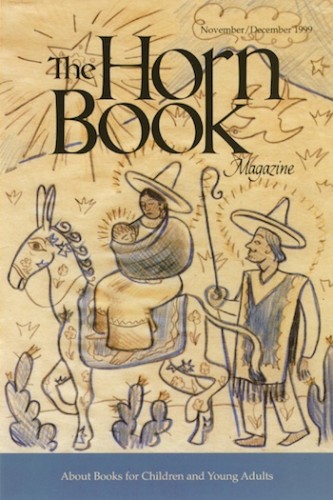

On an evening in November 1930, during Children’s Book Week, Bertha Mahony arranged a festive Mexican Dinner in honor of the authors and illustrators of the season’s bumper crop of books on a Mexican theme. The most imposing, surely, was René d’Harnoncourt, illustrator of The Painted Pig, who was not only a splendid six-foot-six but also an honest-to-goodness Count — an Austrian count of French descent (b. 1901) who had studied chemical engineering, emigrated to Mexico at loss of the family property, immersed himself in Mexican folk art (as artist, collector, consultant), painted a mural for the American ambassador, Dwight Morrow . . . and persuaded the ambassador’s wife, Elizabeth Morrow, to write the text for The Painted Pig. In October d’Harnoncourt’s drawings were exhibited at the gallery of the Bookshop for Boys and Girls, Mahony’s bailiwick, and in December he sent her the drawing on the cover — a folk-Mexican Holy Family with a proud painted horse, a flowering star, and a gently, benignly smoking volcano.

By his own reckoning, d’Harnoncourt was an amateur artist — but he had a keen, thoroughly professional appreciation of art traditions outside the Western cultural mainstream. Within a few years he stopped doing book-work to concentrate on collecting and exhibiting native arts — American Indian as prominently and extensively as Mexican. His flair as an impresario, along with his expertise, took him to the Museum of Modern Art, first as head of the “manual industries” department and coordinator of foreign activities, and ultimately, in the expansionist post-World War II years, as director. Naturally, he was active in the launching of UNESCO.

The year 1930 was “Mexican year” in children’s books generally, but every year was International Children’s Year at the Bookshop for Boys and Girls and its offshoot, The Horn Book Magazine. Partly this was a reflection of the world peace movement, to which Mahony and her colleagues adhered; partly it carried on a long tradition in American children’s books, articulated in Jane Andrews’s 1867 bestseller, Seven Little Sisters: Who Lived on the Round Ball that Floats in the Air. Whatever their color or clime or customs, they were sisters under God, and equals in merit.

In the mid-1920s the gallery held an exhibition of artwork by Mexican children, a nice complement to regular exhibitions of American children’s art, and a show of watercolors by promising young Native Americans, some of whom later won renown for (among other things) illustrating Ann Nolan Clark’s Indian Service primers. The grand-and-glorious Dolls’ Convention, in 1929, was attended by delegates from Poland, Sweden, England, and France; like the old St. Nicholas, the young Horn Book had a number of foreign subscribers. And throughout the twenties and thirties, book after book was prized for its foreign setting, for embodying the values of a foreign culture.

Mahony believed, indeed, that the Horn Book had a responsibility for the world’s children as well as for the world’s children’s books. To her, English children and English children’s books were virtually indistinguishable; or French children and French children’s books. Inevitably, the Second World War, the world’s first Total War, made that concern more acute.

On September 1, 1939, German aircraft and troops attacked Poland; in late November, Russian troops invaded Finland. Neither event is mentioned in the January 1940 Horn Book, but they permeate the issue. Mahony’s editorial, “Finlandia,” stirringly invokes Finnish hero tales; also included is Eric Kelly’s heartfelt “Krakow Is Still Singing,” datelined November 1939; for receptive readers, a list of the Finnish tales is appended.

The next few years brought crushing reverses and new heroes. Finland was forced to surrender to Russian forces and later to accept German occupation. Poland was overrun by Germany in the west and by Russia in the east. Germany attacked Russia, its erstwhile ally, and Japan, Germany’s ally, attacked the U.S. With most of Europe under German control and Britain in danger, Americans found themselves in life-and-death partnership with Russia, Communist Russia, and the numberless, unknown Russian people.

For twenty years the Horn Book had put out feelers for an article about Russian children’s books and in 1943 one arrived, from a Soviet information agency in New York. “Children’s Books in Wartime Russia,” published in the March issue, is boilerplate propaganda by one P. Miller Budnitskaya that concludes with a reference to Arkady Gaidar’s Timur and His Gang, which spawned a patriotic movement among Russian children and which was just then being published in the U.S. More interesting was the follow-up: an article on the young Timurites (published the following January) by Kornei Chukovsky, then known only sketchily as the author of a few translated picture books. He had spent the war years, we’re told, recording the experience of children.

In March 1945, with victory in sight, Mahony launched a series of articles that she had been planning for some time, on the lives and thoughts of children in occupied countries — each to be accompanied, she announced, “by a short reading list.” The first up, fittingly, was Poland.

In a sense, the postwar world caught up with Mahony and other champions of world childhood. The United Nations was organized, UNICEF was founded, and in a few years holiday cards appeared — by the likes of Roger Duvoisin, Joseph Low, and Leonard Weisgard, by Bemelmans, Bettina, and Edy LeGrand — exemplifying the one world of children’s books. In its simple, encompassing reverence, d’Harnoncourt’s 1930 greeting to Bertha Mahony would make a perfect UNICEF card.

From the November/December 1999 issue of The Horn Book Magazine

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy: