Minh Lê & Dan Santat Talk with Roger

Talks with Roger is a sponsored supplement to our free monthly e-newsletter, Notes from the Horn Book.

Talks with Roger is a sponsored supplement to our free monthly e-newsletter, Notes from the Horn Book. To receive Notes, sign up here.

Sponsored by![]()

Minh Lê.

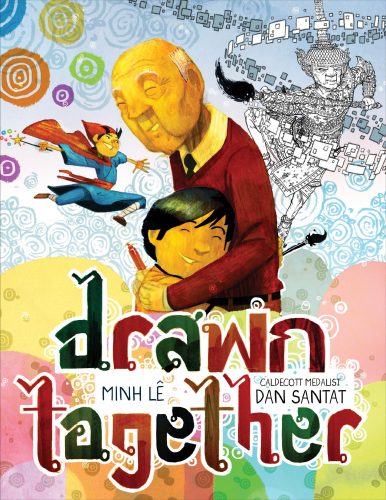

Minh Lê.In Drawn Together, a young boy isn't particularly enthusiastic about spending the afternoon with his grandfather. For starters, they (literally) do not speak the same language. Where can they find common ground?

Roger Sutton: Minh, so much of this story is not in words. How did you communicate that visual narrative to Dan?

ML: When I first had the idea, it was actually a completely wordless book! I wound up putting some light illustration notes into the manuscript to show what the action would be, because like you said, with just the words there's not really much to the story.

RS: It would be a little perplexing. Dan, how did you feel about those notes?

DS: There were more art notes than dialogue — Minh, how many words would you say are in the manuscript? Probably under a hundred, right?

ML: I don't know the exact count, but it took two tweets with room to spare.

DS: From the notes I knew you clearly had a vision of what the world was going to be like. It was important to have those notes in place, because there's something overwhelming about having to create a whole world from scratch. But what I did find intimidating was that you had very simple lines: "We build a new world that even words can't describe." That's quite a task! So I thought a lot about how a young child would contribute and how an older grandfather would contribute to an artistic collaboration. Minh was very loose in the manuscript; the family was of Asian descent, but he was open as to which culture. As an Asian American author-illustrator, I had never really taken the helm of illustrating something that was culturally specific to myself. You have your Grace Lins and your Gene Yangs, who do these very Asian-centric books about culture. And then you have me drawing funny robots and pigs and things like that. This was a good opportunity for me to inject my own Thai culture into a project. I'd have to say there was a little bit of guilt involved, that I hadn't participated more. With that said — because Minh is of Vietnamese heritage I didn't want to overstep my bounds.

RS: So that's Thai I am reading here?

DS: Yes. My parents helped me do the translations. When you see the grandfather's dialogue in Thai in the book, that's my mother's handwriting. I told her I was going to put it in the book, and she ripped up the paper and said no, no, let me write it better. My parents have been living in America for over forty years now, so they were a little rusty. They'd call my aunt back in Thailand to ask, "Did we get this right?" At the same time, I'm not even sure it's really relevant that it's Thai.

ML: Dan, I wish I'd know that you were worried about overstepping by making the family Thai. My hope all along was that that's what you would do. I didn't want to push you in a certain direction, but I had my fingers crossed that you would have a personal connection to the story and make it your own. For this type of manuscript to work, I knew Dan would have to take it to another level.

Dan Santat.

Dan Santat.RS: Were you guys a team from the start for this book?

DS: No, our editor, Rotem Moscovich, approached me with the manuscript. I remember reading it and wishing it was something I had written. Minh has this great way of keeping a manuscript to its bare essentials, just the core of the story. It's difficult for a lot of people writing picture books to trim the fat. It was a no-brainer to take this project. It was one of these things where I looked at my schedule and thought, "I don't know if I have time to do this, but I'm going to make time to do it."

RS: The two of you have one of the best page-turns I've seen this season: "My grandfather surprised me by revealing a world beyond words." And then, "in a FLASH" — page-turn — we see the boy's art and the grandfather's art on facing pages. It's really quite something.

DS: Something about Minh's manuscript very much lent itself to the page-turn. It really pushed my artistic abilities. I'm not drawing the book as Dan Santat, illustrator; I'm embodying the characteristics of the grandson and the grandfather and trying to come up with a style that they would have created together. I was being mindful of what materials a kid would use — markers, watercolors, crayons and about the grandfather probably being a little more disciplined with a pen and ink. Rotem was getting a little nervous towards the end, because the art for the book was taking a lot longer for me to finish than usual. She knows it takes me about a month and a half to fully illustrate a book. This book was running about three months, and Rotem would just pop her head in and say, "Is everything okay? Do you need anything?"

RS: And what were you doing all this time, Minh?

ML: I was just twiddling my thumbs! I feel like I found a cheat code for making books, because I'll write this very spare manuscript that's about a page, front and back, and then hand it off to an illustrator like Dan and watch it slowly unfold into this beautiful book.

RS: Minh, what surprised you the most about seeing the story that was in your head as you see it now?

ML: Dan took the art to a level I couldn't have possibly imagined when I was writing, but at the same time, it's exactly the book I had in mind. The vibe and the sensibility, how he used color, the two different styles. It was amazing to see how his execution at every step mirrored my unspoken hope for the book. There's one image where the grandfather grabs the boy's magic wand, and all of a sudden he's turning from black-and-white into color. After the fact I realized that I had never put that note in the manuscript, but that's exactly how I was hoping the color would come through. It becomes an important part of the story.

RS: On the spread roughly in the middle of the story — with the grandson's drawn character on the left and the grandfather's on the right and the chasm between them — what is "that old distance" that "comes ROARING BACK"?

RS: On the spread roughly in the middle of the story — with the grandson's drawn character on the left and the grandfather's on the right and the chasm between them — what is "that old distance" that "comes ROARING BACK"?ML: For me, that refers to the still-present threat of not being able to communicate. While the two characters do find common ground through their art, I thought it was important to show that things weren't all of a sudden easy or perfect. There are still going to be moments when the characters struggle to connect. The important thing is that, whereas at the beginning of the story they might have given in to that distance between them, now their relationship is strong enough that they both make the effort to bridge that gap.

RS: Forgive my cultural ignorance here, but is there anything traditionally Thai about the medium or the style the grandfather is using?

DS: What's interesting about modern-day Thai culture is that art is not really a profession per se. If you go to Thailand a lot of the art on display is appropriated from other Asian cultures, or borrowed from other cultures and then translated. What do exist in traditional Thai culture are mostly the sculpture, tapestries, and paintings that you would find in Buddhist temples and so forth. My uncle, my father's brother, is a pharmacist, but as a hobby he's an artist, and he paints with ink and pen. So that's where that comes from in the book.

RS: Was that something new for you?

DS: I'm known for working digitally in my picture books — I would say that forty percent of my illustration work is traditional (which I then composite on the computer) and the other sixty percent is enhanced digitally. With Drawn Together, I would probably say it's eighty percent traditional and twenty percent digital. I really wanted to get that hand-drawn feel. As a result, this book changed me as an artist. Now I find that I've gone in the direction of more traditional art. For five years or so I felt stuck, like I was doing the same kind of art for books year after year. I was starting to get stale, maybe a little bit bored. Drawn Together broke my habits and made me evolve into something different. Not to say that I ever took the job of illustrating books lightly, but it's exciting to know that you can still discover new things in your craft after you've been doing it for about fourteen years.

RS: Minh, this is your second book, correct? [Let Me Finish! illustrated by Isabel Roxas]

ML: Yes.

RS: And what does it teach you for the third? What do you know now about making picture books you didn't know before this one?

ML: It's not so much that I didn't know this before, but it's been hammered home — the importance of leaving that room for the illustrator, keeping the text to its most streamlined format. Letting the process play out and seeing what the illustrator comes up with. That's how I like to write. I think very visually. If I had the skill I would illustrate myself, but I don't. The stories I like to tell are told through the illustrations, and it's fun to watch them unfold. Dan shared so many sketches via Twitter or Instagram in real time.

RS: Do you ever regret that, Dan?

DS: I like sharing process stuff. I know there are people who don't want to show anything unless it's perfect. There's a lot of talent that never actually gets published because of that. I think it's important to show that everything you create is a process. Nothing's going to be perfectly polished. In my experience publishers embrace sharing the process, because they know it breeds anticipation for a project. One of my favorite things to do is to show a piece of art that actually hasn't made it into a book. It's like a DVD commentary, where you're showing the thought process behind things. When I'm working on something, I give a lot of thought to why it should be done in a certain way.

RS: Dan, what's the best piece of advice you ever got from an art director?

DS: One of the best art notes I ever got was, "You make the book that you want to make, and then I'll pull you back if you've gone too far." It left me free to go the direction I wanted, and to know the art director would steer me in the right direction if I'm off course. I've had other projects where the art director would say, "Okay, this is how the spreads are. Illustrate this and this." It's very rigid, restrictive, and I don't feel like you get the best product at the end. Being free to express yourself, I think, is the best policy.

RS: Minh, what's the best piece of advice you ever got from an editor?

ML: I've only worked with Rotem, who's amazing. It would probably be something along the lines of, "Trust the process." There's so much that has to move forward between when I, as author, hand things off to getting to the finished book. There's a lot of negative space for a writer to sit and angst over what's happening. Letting go and trusting everyone along the way is the best approach when so much of it is out of your hands.

RS: Not a bad approach to life, either.

More on Minh Lê & Dan Santat from The Horn Book

- 2016 in Review: "The Year in Pictures: Somehow Still Beautiful by Minh Lê"

- Profile of 2015 Caldecott Medal winner Dan Santat by Connie Hsu

Sponsored by![]()

RECOMMENDED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!