Jewell Parker Rhodes Talks with Roger

Talks with Roger is a sponsored supplement to our free monthly e-newsletter, Notes from the Horn Book.

Talks with Roger is a sponsored supplement to our free monthly e-newsletter, Notes from the Horn Book. To receive Notes, sign up here.

Sponsored by![]()

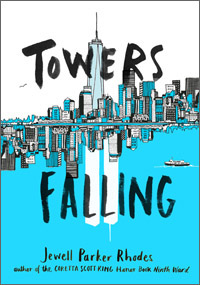

While most adults (for now) count September 11th, 2001, as memory, for today's fifth graders it is history, if known at all. Dèja, whose family has moved from living in a car to staying in a homeless shelter, hasn’t heard of it, although the attack has had a tremendous impact on her life, something she will come to understand as she begins the year in a Brooklyn school with a heartbreaking, inspiring curriculum.

While most adults (for now) count September 11th, 2001, as memory, for today's fifth graders it is history, if known at all. Dèja, whose family has moved from living in a car to staying in a homeless shelter, hasn’t heard of it, although the attack has had a tremendous impact on her life, something she will come to understand as she begins the year in a Brooklyn school with a heartbreaking, inspiring curriculum.RS: What do you remember about September 11th?

JPR: I was in bed in Arizona. I was not in New York City. I think if I had been in the city, I might not have been able to write this book. My husband called me downstairs to watch the coverage on television. The two of us were absolutely grief stricken. It seriously affected my mental health. I went into a depression — I just felt shaken to the core. I think the only thing that got me through was the idea that, given all the people who died or were wounded or lost their loved ones, I should take care to live my life to the fullest, and part of that is being a writer. In that sense, I’m connected to the event by my desire to do something to honor the 9/11 survivors and those who didn’t survive. Something that moves our society forward, something that engages children in what it means to be a citizen and encourages them to love and be inclusive. Because if we don’t live our lives well — if I don’t live my life well — it’s an affront to all the people who were involved in the tragedy of 9/11.

RS: What experience have you had sharing 9/11 with young people? Was there any child in your own life you needed to tell about it?

JPR: No, and in fact the idea for writing this book wasn’t mine at all. It came from Liza Baker, my editor at Little, Brown, at the time. She had seen on 60 Minutes that children were growing up not knowing about 9/11, and she said, “Would you like to try writing this book?” I immediately said, “Nope, I’m not going to do it.” The more I thought about it, though, over several months, it burrowed deep inside my soul. My background is in teaching, and I love the idea of teachers teaching my books. That helped me frame the novel in a fifth-grade classroom, which gave me distance from the event itself. It also gave me room to imagine how an elementary school curriculum would teach it, as well as how the children themselves would perceive what happened, particularly if they find out that 9/11 has affected them quite personally. I think that’s the key to this book. When I actually went and visited schools, I learned they were not teaching 9/11, that the teachers felt the trauma was too immediate. Yet the world has changed so much because of terrorism, so much since 9/11. It seemed wrong to me that children did not have a sense of it, a place to talk about it, to understand how the world they’re growing up in is unlike any other world we’ve ever had before. It should be discussed. It shouldn’t be off-limits.

RS: I was thinking about how when I was a little kid in the early sixties we would play war, like World War II. And it seemed completely separate from our own lives, even though our fathers had fought in that war.

JPR: That’s very interesting. Maybe it has to do with distance, the fact that World War II happened very much abroad.

RS: That’s true.

JPR: In American history, there are only six times that we’ve had actual attacks on our soil. It becomes visceral in a new kind of way. One of the things I was made aware of is that kids today understand their dad or mom is off at war. Iraq and Afghanistan have been such long wars and so many people have been involved in them, that children are aware of things like post-traumatic stress syndrome and redeployment. And if you also look at the phenomenon on YouTube of all the videos of soldiers coming home and surprising their children—

RS: And their dogs.

JPR: And their dogs, yes. Children’s lives are more touched by 9/11 and service people going to war than we think.

RS: I agree.

JPR: That’s what I try to confront in the book. Dèja doesn’t know that her dad’s anxiety and stress come from being a 9/11 survivor.

RS: How do you write a book about 9/11 without people saying, “Oh, it’s an issue book”?

RS: How do you write a book about 9/11 without people saying, “Oh, it’s an issue book”?JPR: I never thought of it as an issue book. I believe in character-driven fiction, and I can’t write a book until I hear a character’s voice. Dèja’s voice came so clearly to me. All of the children’s did. I saw the story as a mystery for her, discovering how this thing that happened fifteen years ago impacted her family’s life to the point where her family is now homeless.

It’s also a story of how adults, when teaching and sharing traumatic events, sometimes tread very, very carefully because they think children aren’t ready. And how kids are often much more ready than we give them credit for. Teachers, of course, are doing a terrific job, but I think kids are far more hungry, far more knowing. It’s about their own individual rites of passage. So I don’t see it as an issue book at all. I see it as kids uncovering mysteries. If readers aren’t caught up in the story, caught up in the journey of these characters, then it would be a failed book. My job is to make kids feel immersed in a world, make them hear the voices and go on these journeys of discovery. That’s true whether I’m writing about Hurricane Katrina, the BP oil spill, or the Twin Towers falling. First and foremost it’s a story that’s centered on children.

RS: That’s why these events stay with us, because of the effect they had on people.

JPR: Exactly. That’s what makes it critical. What happened to the individual, the friend, the community, the society. That’s what I’m writing about.

RS: Throughout your book, you’ve got these Venn diagram maps that the kids make of themselves and their families, friends, community, etc. Don’t you think time works that way too? We build those circles over the length of our lives. What happened to Dèja’s father was years before she was born, but nevertheless, that reverberates with her today. She doesn’t know why for most of the book, but it does.

JPR: Exactly. It underscores the idea that history is always relevant. It’s always personal, because it involves human beings. The way to confront or triumph over adversity, over tragic historical events, is that social network of family, friends, community, nation. The Venn diagrams are also connected to me. I went to visit P.S. 146, where they had a wall of windows and actually saw the towers being hit and then falling. I asked if they teach about 9/11, and the answer was no; the trauma was too real, too recent. But they were teaching a unit on the Holocaust, and one thing that was really critical was starting with the concrete: If you had to leave your home and you could only take one suitcase, what would you bring? And then, of course, as the tragedy marches along, more and more things are given up. That was also an entryway into Towers Falling. Of all the things that are so concrete and so important in this world, we come up with the notion of home as the most important thing. What is home? In the novel, home is not a building. Home is a social network. Home is that community. And from there we build our American home.

RS: I love the way you had the kids acting on their own. As you said, the teacher is very careful about parceling out the information about 9/11, but the kids can just get on a computer and find out anything they want.

JPR: Can you imagine that? Nobody did that for the Revolutionary War, the War of 1812. Children today have access in the blink of an eye. They can see these things happening. For me, watching footage of the towers burning and the towers falling, all I feel is the horribleness of that day. The real truth is that in terms of our country’s response, the bravery, the courage, the sense of patriotism, the unity — our response was beautiful. That beautiful response is based in our founding principles, what has kept us together as a nation over all the different problems we’ve had to deal with. I wanted kids to have context for seeing that horrible footage. I wanted them to feel the patriotism that united us, the sense of inclusivity, of not discriminating against religions. I want that feeling back, and I want to remind kids — and all of us — that we have a tremendous power when we remember our history and our founding principles.

RS: So, how are you feeling about that now, in this election season?

JPR: When I was watching the conventions, I felt that my students in Towers Falling could teach the politicians a thing or two. I really did. Children know you ought to be fair. Especially fifth graders. I love fifth graders. They know that bullying is wrong. They know that you should praise one another, and that differences make a strong community. So sometimes I feel as though I can’t wait for the fifth graders to grow up and rule the world. I think my book is a really good reminder that divisiveness will never work in America. Or if it does work, then we’ll no longer be the country that we think we are.

RS: What do you think, for you, is so special about fifth grade?

JPR: I have to be honest and say it’s the hugs. They’re just at the moment between being a child and growing into that man or woman they’re going to be. It’s a critical, focused time, and yet they’re not shy about sharing affection. They’re not shy about telling the truth. They’re optimistic.

I’ve been waiting a long time to be a children’s book author. I’ve spent decades getting good enough to write for children. When a kid likes my book, or just likes that I'm visiting and talking to him or her, and I get a hug, I feel reborn. That hug that says you made a connection — there’s nothing better in the whole wide world.

Sponsored by![]()

RECOMMENDED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!