Cynthia Voigt Talks with Roger

Talks with Roger is a sponsored supplement to our free monthly e-newsletter, Notes from the Horn Book.

Talks with Roger is a sponsored supplement to our free monthly e-newsletter, Notes from the Horn Book. To receive Notes, sign up here.

Sponsored by![]()

Photo: Michael Lionstar

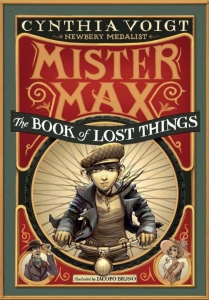

Photo: Michael LionstarCynthia Voigt's latest book, Mister Max: The Book of Lost Things, is a largely comic Victorian mystery that seems miles away from the tough stories of Dicey Tillerman or the Bad Girls. But as I talked to Cynthia, and as I thought more about Mister Max's redoubtable grandmother, I realized some things don't change.

Roger Sutton: We're seeing lots of vaguely Victorian-set mystery series for middle-grade readers, but most of them come accompanied by these unctuous narrators winking at us, winking at the characters. We don't know if we're supposed to take this seriously or not. But you're very straightforward.

Cynthia Voigt: I am. I don't think I can be ambiguous. I'm essentially a very earnest person. I can't write that complicatedly.

RS: When you're writing a light mystery, how do you balance the need for danger with the security that this kind of series has?

CV: This book is not about horrible things that happen. It's a book about the kid and the world he lives in, and I just never wanted to go where there was death and disaster. Not for Max.

RS: And we feel assured, as we're reading it, that you're not going to go in that direction.

CV: That's true. You're probably pretty sure I'm not going to kill him off. Which I've been known to do.

RS: The mysteries will be manageable.

CV: Yes. And they're not so much mysteries, they're problems. Which is one of my messages, over and over, it seems, in my books: you can solve a problem.

RS: Max calls himself the "solutioneer."

CV: The solutioneer, yes. It's a good attitude to life.

RS: Man, I'd like to have one of those.

CV: Yes, on hire.

RS: This book is planned as first in a trilogy. You’ve written several series before, but they weren't planned as such, were they?

CV: No, all of the other ones were accidental. You'd write one book and then the next one would be in your head.

RS: When you wrote Homecoming, you thought it was originally going to be two books, and that you thought of Dicey's Song as the third book.

CV: Yes. I thought of Dicey's Song as Homecoming Part III.

RS: But from the start you didn't say, "Okay, I'm going to write about this family of kids that's going to travel down the coast to Grandma." What's different when you do have something planned out to begin with, as this series is?

CV: Interestingly enough, the original contract was not in place until I had drafts of all three books, which was not like things had been before. Of course when you write a mystery of any kind, I find it always requires a lot of revision, because it's the hardest thing I know to write. To write a mystery, for me, is so anti-intuitive. You have to be so much more self-conscious at the typewriter than I often am when I'm writing.

RS: With a mystery you have to have a certain amount of calculation in your writing.

RS: With a mystery you have to have a certain amount of calculation in your writing.CV: Yes, and if I'm writing by intuition, generally that calculation works itself out. But if I'm writing a mystery, and somebody has to have a reason for doing what he's doing, and it's not anything I can imagine myself wanting to do, things get a little more difficult to write, and careless mistakes are made. Thank God for editors. I knew where the book began and I knew where it ended, and it turned out I couldn't get it done in one book. So I thought of three, and that seemed to work out. And then I thought of four, and then I thought of three. Three is a good rhythm for this particular story. Mister Max is the book of lost things. The next is going to be the book of secrets. I get to play around with a lot of patterns. It's just a different way of plotting things.

RS: Is Max ever going to leave home?

CV: Yes. Don't you like his house?

RS: I do like his house, but I'm worried about his parents.

CV: I know. We should be. But not too much, right? It's not haunting you.

RS: Right. Well, as we said, it's not that kind of book. But it's nice to have these overarching questions — where are my parents, what's going on? — along with the solvable problems that Max takes on very methodically, or sometimes accidentally, but that he manages to fix. And you can watch them go click, click, click?

CV: I love click, click, click.

RS: Things fit together.

CV: Yeah. Clearly, I've had a very good time.

RS: When you're writing a book like this, as opposed to — oh, to be extreme, When She Hollers, which was this horrifying novel for older kids about abuse — does the writing feel different? Are you happier?

CV: It's less painful to be considering what you might be doing in the next scene. But on the other hand you feel less urgent about it. To write with a firebrand in your hand, to feel the utter importance and rightness of every word you're putting on the page — When She Hollers was, in a way, easier to write, because it had all this emotion behind it. But it wasn't as much fun. Even the bad books I write are satisfying. I'm my least critical reader.

RS: So you enjoy sitting down and doing it. You're not like Judy Blume, who hates to write but loves to revise, for example?

CV: I love to write. I love to revise. I don't love to reread. But that's okay. I'm not a suffering artist.

RS: Have you found that your attitude toward your writing has changed over your career?

CV: Yes, my attitude has changed. I no longer have any hope to write the book that will save the world.

RS: I think reading can save the world. It's not writing that saves the world.

CV: I agree with you.

RS: So what's different now for you about writing?

CV: I consider myself plotting-impaired. That's hard.

RS: Especially if you're writing a mystery.

CV: I got used to being a writer. To compare it to teaching — I taught for twenty-five years; Horn Book executive editor Martha Parravano was one of my students! — for the first two or three years it was heady. I was discovering that I could do something and do it well. Be useful to people. It was exhilarating, sort of like the first two weeks of being in love with somebody, and then it becomes like the third bite of pizza. The first bite is wonderful. The second bite is not disappointing. The third? Meh. You get used to it. You know how to do a lot of the stuff. Some things, like the joy of being in a classroom, or teaching Hamlet, never fade. But some things are not so exhilarating. It's what happens when you get accustomed to something.

RS: Right.

CV: So that's what's changed. Nothing essential, I don't think, but the periphery.

RS: I also think that even in those things that you get used to, even though the newness is gone, that exhilaration, there's the satisfaction of knowing what you're doing.

CV: Right. And there's the deep-rooted relationship you have. You become more and more the work that you're doing, in a way that you can rely on and trust. The honeymoon ends, but then in a way love begins.

RS: This is all very philosophical and well reasoned. In the book, your hero Max likes to paint to sort things out. What do you do?

CV: I used to lean back in my chair and light a cigarette, but —

RS: Those were the days.

CV: Those were the days. Now if I just need to sit back and rest or keep a scene from going entirely awry or discover something I've done wrong or right, I might pull up a game of Freecell on my computer screen. Or I might walk around. I'll walk around, or do a jigsaw puzzle. I have a jigsaw puzzle thing that I've taken up recently.

RS: Real or virtual?

CV: Real. Wooden pieces. I'm not messing around here. You set them out on the table and you spend five minutes with your fingers doing things. It's like having a dinner party where you serve lobster. Your hands are busy and the talk flows.

More on Cynthia Voigt from The Horn Book

- "Have a Carrot:" Cynthia Voigt on The Runaway Bunny

- Profiles of Cynthia Voigt to celebrate her Newbery Award win

- Martha V. Parravano runs into three Newbery winners at ALA 2013

Sponsored by![]()

RELATED

RECOMMENDED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy: