Molly Idle Talks with Roger

Talks with Roger is a sponsored supplement to our free monthly e-newsletter, Notes from the Horn Book.

Talks with Roger is a sponsored supplement to our free monthly e-newsletter, Notes from the Horn Book. To receive Notes, sign up here.

Sponsored by![]()

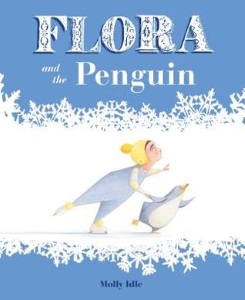

After winning a Caldecott Honor Award for Flora and the Flamingo, Molly Idle and her doughty heroine have jeté-ed from the ballet onto the ice, where Flora and the Penguin engage in an impressive pairs routine.

After winning a Caldecott Honor Award for Flora and the Flamingo, Molly Idle and her doughty heroine have jeté-ed from the ballet onto the ice, where Flora and the Penguin engage in an impressive pairs routine.Roger Sutton: Let's talk about your very wintry book. Have you ever been ice skating?

MI: Yes, twice. Both with terrible results. My mom took me when I was tiny, and I just remember that feeling of the ice being so cold on your hands when you fall that it would burn. The other time was with my best friend. I'm a good roller

skater, and she said, "We should try ice skating." I managed, just, to hold on to the edge of the rink to get myself around. When the session was over I was on the opposite end, and the rink referee thought I was playing for time. She pulled me away from the wall, sort of swung me out into the middle of the rink, and let me go. And I promptly fell down. And I'm crawling on my knees, trying to get across the rink as the Zamboni is slowly, slowly coming. It was like a terrible horror film.

RS: What persuaded you to put Flora on skates?

MI: It was my art director, Amy Achaibou. We were working on Flora and the Flamingo, talking about how I was going to treat the water that they were dancing in, and she said, "You know, the way you're handling it makes me think of ice." I said, "If it were ice, she'd be dancing with a penguin." And we looked at each other and went, "Oh! I think we are going to make another book."

RS: It's really amazing to me the amount of movement that you get in here — not only within each picture, but then from one page to another, and then with the flaps. You're balancing an awful lot of elements.

MI: For me, these books are all about movement. I'm very conscious of trying to keep the poses moving, and to utilize the flaps for times when one pose just isn't enough to convey what's happening.

RS: How do you decide between a flap and a page turn?

MI: I tend to use flaps when there is a moment of choice for both characters. With page turns, the characters are more in sync. They're — this is a terrible pun — I was going to say they're on the same page. So it seems natural that we turn the page and we find them together. I tend to use the flaps when the characters are making choices that may put them at odds with each other, or when I want the reader to be able to make a choice as to how the story progresses. It's like this tightrope of control. I want the story to go a certain way, but I also want the readers to be able to play a very active role.

RS: With any wordless book each reader has to make a choice about what "this happens" actually means. You're giving up an awful lot of control by not directing the narrative with words.

RS: With any wordless book each reader has to make a choice about what "this happens" actually means. You're giving up an awful lot of control by not directing the narrative with words.MI: But I also think it's really powerful to give up that control, and that's something that I struggle with — I think all artists struggle with — in their work. It's a collaborative process, making books. It would be so easy to keep hold of this little idea that is precious to you. But in sharing it, collaborating with editors and art directors, it becomes something even more. And hopefully better than you could ever have come up with if you had just kept it all to yourself. And that happens again, exponentially, when you give it over to the reader. You've controlled how it started, and where it's going to end up. How you get there, give that to the reader. It’s tremendously empowering for them.

RS: They get to make their own choices. Certain actions are on the page, and you can't really argue with the actions, but you can argue with the motivations for the actions.

MI: The motivation and your interpretation. I love watching kids, or listening to kids, tell me the story. Sometimes it's totally different than what I imagined.

RS: Flora has run away from her horrible mother. She finds herself...

MI: ...alone, in the Arctic tundra. Yeah, I haven't stopped to think about the backstory.

RS: What did that flamingo do to her?

MI: She left the tropics and went someplace to cool off.

RS: Do you think you'll take her anyplace else?

MI: Right now I am working on Flora and the Peacocks.

RS: What are they going to do?

MI: They are going to deal with the dynamics of relationships of three. It's tricky, because often somebody feels left out. How do you keep everybody happy, or at least working along together?

RS: Threesomes are really complicated.

MI: Yeah, even when you're a grownup.

RS: How did Flora and the Penguin evolve? You said you had the idea while you were still working with the art director on the last book?

MI: With the first book I brought a complete dummy. There was no background, no flowers, it was just the characters and all their poses. And that was very much the same with this one. We started with a brief conversation. I said, "I think it would be nice if we had Flora be a bit of the antagonist this time." Then I went back and worked on the poses. We knew we wanted to use flaps again but in a different way. That was really important to me. These are double-sided, and they move back and forth. We knew the characters were going to be on ice, but how was everything going to be divided? And in fact the entire book was run through once before we ever had the idea of having the schooling fish go around underneath.

RS: That's a great parallel story going on underneath there.

MI: Thank you. That was many hours spent, wondering about the motivation of fish.

RS: They go this way. They go that way. Then they change direction.

MI: We just wanted them to be fish, and we had very deep conversations — were the fish characters, or were they more of a background element? Did we want to become terribly attached to the fish, given how it ends? But I think, thanks to Jon Klassen, the way has been cleared for fish being done away with.

RS: Right. And penguins do love fish.

MI: They do. And I didn't feel bad about letting him get one in the end, because that's what they do. It felt very natural.

RS: Flora has her moment of squeamishness.

MI: Unfortunately I don't like to fish, and I projected that onto her.

RS: How do you get this really beautiful sense of movement from our two characters? It's amazing.

MI: I'm heavily influenced by my background in animation. After I figure out (using thumbnail sketches) what the choreography is going to be, I take all the actual drawings, even the ones that don't have flaps, and lay them one on top of the other or flip them, like animators do, to make sure that they can move. So you could — well, I couldn’t, because I can't ice skate — but if you could ice skate, Roger, you could actually do this whole dance.

RS: That's what it looks like.

MI: Pose to pose. It's like a puzzle for me. I'm sure we could skip steps, but I enjoy trying to figure out how to move the story along while actually physically moving the characters into different poses. I block it out like an animated scene in my mind. Dance and choreography really lend themselves to the wordless picture book in that way. You can strike these wonderful, exaggerated, slightly theatrical poses, but it still feels genuine in a way it wouldn't be if your character was just standing in the middle of, I don't know, a classroom, and suddenly jazz hands. When the story's about movement, somehow that movement feels more sincere than if you just slap it on top.

RS: What are the different freedoms and limitations of working in animation as opposed to creating a page-turner, so to speak?

MI: The upside of animation is that there are all of these drawings per second to flesh out a film — something like twenty-four drawings per character per second. There are a lot of drawings that you have to make to get you from point A to point B that aren't really too beautiful — they're called "in-betweens." For a picture book you have to pick just those really important moments to illustrate. But then when you have it, I think it's more powerful visually. When something is playing for you on a screen, you only get one person's vision of how that story plays out. In a picture book, the reader gets to be the director. You get to choose how long you're going to linger on that page, in that moment, before you turn.

RS: And a reader can go back and forth, too.

MI: Yes, exactly. To your heart's content. With Flora and the Penguin you can have them skate back and forth for an hour if you like.

RS: I'm intrigued by what you're saying about the in-between sketches. One thing you do really well is get from one big moment to the next. How do you choose?

MI: It comes down to thinking about how the characters would react. There are no words to bridge the gap, so I have to put myself in the mind of this penguin. How does he feel? When you step through it this way, emotionally, that also helps with stepping through the poses. Inasmuch as this is a book about ice skating, it's really about body language, which is something we're all familiar with on an instinctual level. There's one pose near the end of the book — I don't want to give anything away — but when Flora's taking off her skates, and the penguin is totally dejected. I wanted very much for it to feel like they were done, finished. I said that to my art director, and she said, "I didn't think that at all." And I asked, "Why not? Is it the pose? The composition?" And she said, "No, I just know Flora's a nicer person than that." So that was her interpretation. That gives us a choice. Even though I was thinking something totally different, she felt like when we turned the page, it was anticipatory of the solution, and I felt that it was instead building up the tension, and it turned out that we could both be right. And I thought, "Well, that's good, because no matter how kids are feeling when they're reading it, they're going to be right when they turn the page."

RS: Right. When I first went through the book, on that spread I thought the penguin was just worn out.

MI: Oh, see, there's another good one.

RS: But if you look closely, he does have this mean little look in his eye, grrrrr, like he's frustrated and irritated with her.

MI: Yes. Then she comes along on the next page. "I'll help you. You're tired. You're angry, I'm here to say I'm sorry." I'm anxious to see what kids think when they turn the page.

RS: Have you shared, in a storyhour kind of setting, either of the Flora books with kids?

MI: Yes.

RS: How do you do it? When I was a librarian, wordless books were always tough.

MI: I generally just say, "This is a wordless book so I'm not going to talk. We'll all just look at it together." It works best with small groups, no more than fifteen or twenty, so they can all get up close. But then suddenly everyone feels like they need to be quiet, and that's no fun. You want to hear what they're thinking. You want them to be able to laugh if they want to. So sometimes I'll turn a flap and go, "Oh!" and raise an eyebrow, and suddenly they're doing it too. It's really wonderful to see — or hear, actually, because almost nobody voices anything with words. It's all a lot of sound effects, like aw or oh or ha ha ha. And when it's over they usually clap, which is interesting to me, because that doesn't normally happen at storytimes. I think it's viewed as more of a number, which ends in applause. I love that they're so excited when none of us has said anything — it's all the story in their heads. Each kid could be totally excited about a whole different thing having played out.

RS: Well, if you wanted words you would've put in the damn words.

MI: I want these books to be about something so big that any words you would add couldn't be enough; it's a feeling we can't necessarily put into words.

More on Molly Idle from The Horn Book

- Starred review of Flora and the Flamingo

- Molly Idle on Flora and the Flamingo

- Calling Caldecott: Lolly's thoughts on Flora and the Flamingo

Sponsored by![]()

RELATED

RECOMMENDED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy: