Marla Frazee Talks with Roger

Talks with Roger is a sponsored supplement to our free monthly e-newsletter, Notes from the Horn Book.

Talks with Roger is a sponsored supplement to our free monthly e-newsletter, Notes from the Horn Book. To receive Notes, sign up here.

Sponsored by![]()

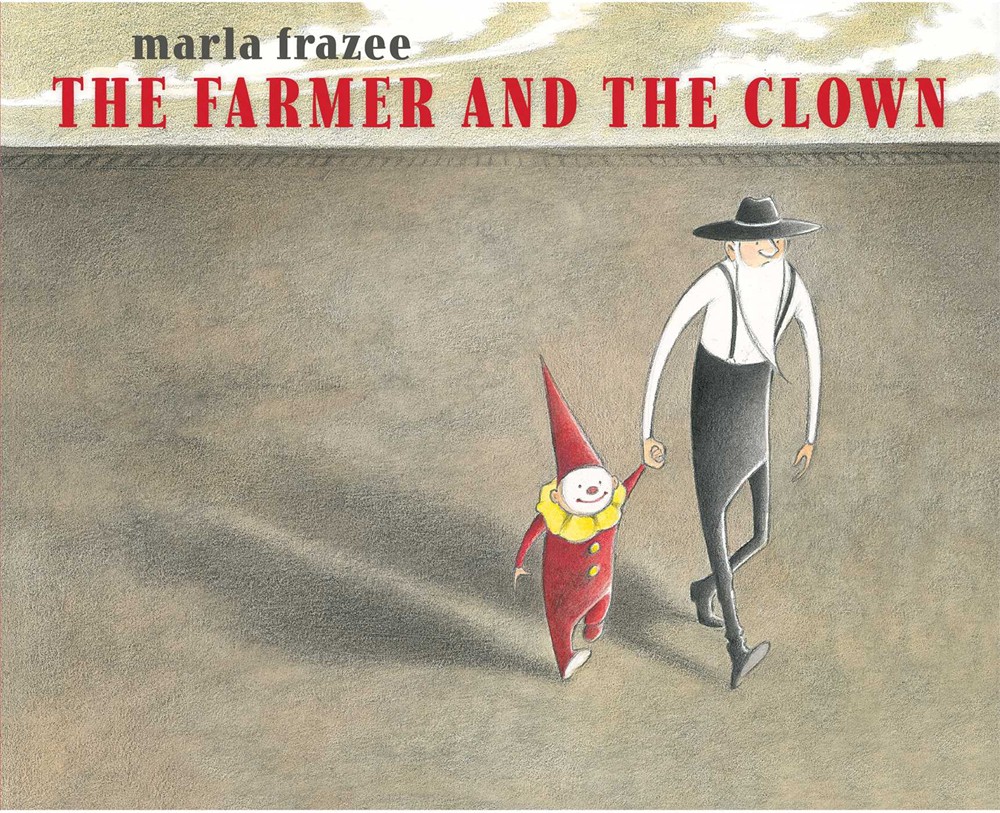

Two-time Caldecott Honor recipient (for A Couple of Boys Have the Best Week Ever and All the World) Marla Frazee's newest picture book The Farmer and the Clown is already garnering talk of award recognition. Wordless, but rich with narrative and emotional resonance, The Farmer and the Clown portrays an unlikely friendship in which one party seems to rescue the other — but maybe that's exactly backwards.

Two-time Caldecott Honor recipient (for A Couple of Boys Have the Best Week Ever and All the World) Marla Frazee's newest picture book The Farmer and the Clown is already garnering talk of award recognition. Wordless, but rich with narrative and emotional resonance, The Farmer and the Clown portrays an unlikely friendship in which one party seems to rescue the other — but maybe that's exactly backwards.Roger Sutton: This is a really amazing book.

Marla Frazee: Thank you so much.

RS: The emotional quality of the story is incredibly powerful. So many of the pictures choke me up — they would probably have me sobbing right now if I didn't have a reputation to maintain.

On your website you ask yourself a bunch of questions that you say people always ask you, and one of them is, "What is more important, style or concept?" Your answer: "I think the most important thing is emotional engagement." How does an artist create that? As you've certainly done in this book.

MF: For me, I think it's through time. If I'm sort of hooked into an idea, I try to play it out in my mind to see whether there's something there to follow — what I would call the beating heart of that idea. If I can't find it, I won't be that engaged in the idea anymore. Even if I do find it, I often don't know until many years later why it was compelling to me. As an example, when I started working on the Santa book [Santa Claus: The World's Number One Toy Expert], in the beginning I just thought it was really funny that Santa would be a toy tester. That was how the book started in my mind, and I played with the idea for years. It wasn't until maybe seven years down the road, when I was on a long drive, that I realized he would have to know children really well, and know toys really well, in order to match the child and the toy, and that it was about gift-giving. It was about something we all aspire to know how to do — to give the right gift at the right time. Once I had that, the book started to make sense to me. Before that, it was just...

RS: This idea.

MF: Yes.

RS: What was the genesis of The Farmer and the Clown, emotionally?

MF: This one was very interesting, because I don't know if you like clowns, but I don't like clowns.

RS: Me neither.

MF: Most people don't like clowns. But for whatever reason, I went to this clown show performance at my kids' high school. The performers had worked on their clown personas for weeks, at least, and then acted in skits. It was set to music (there was no speaking), and it was really compelling and evocative and sublime. I loved it. I couldn't get clowns out of my head afterward. So I thought maybe I should do a book about a clown town. Everybody's a clown. They shop, they go to school. But somebody moves in who isn't, who's a serious person — what would happen? And then I reversed it out. Maybe it should be a serious town and funny neighbors who move in. There's something funny about the new neighbors, and it's a clown family.

RS: The clown comes to town.

MF: Yes. But then I was watching a Modern Family episode where Cam is a clown, and all his clown friends cram themselves into a Mini Cooper after a funeral. And I thought, "Well, there goes that idea." Then I was playing with the idea of a little clown who was teaching a yoga class, but there was no story. And there wasn't a story for a really long time. Then I thought of two characters — a serious, Amish-like farmer holding the hand of a very smiley baby clown, and they were walking together. It just hit me, that image. That's where it started. And I thought, "There they are. Those are my characters." Then it was a question of why are they together? What is the story that brought them together? It came from the fact that they both had such different personas, really, from what they truly were. We think: the clown has a big smile so that means he's happy, and we maybe think the farmer's a grump, but there's more to him than that.

RS: We have that amazing scene of revelation where on the left-hand side of the spread, you see them getting to know each other. They're talking. And then they're eating. And then they're washing up for the night, and the makeup comes off the clown's face. And to the old man, at least the way I'm reading it — and of course, it being wordless, we can read it however we want to — it's like a completely different person he's now encountering. That he finally sees the clown as a baby, or a little child.

RS: We have that amazing scene of revelation where on the left-hand side of the spread, you see them getting to know each other. They're talking. And then they're eating. And then they're washing up for the night, and the makeup comes off the clown's face. And to the old man, at least the way I'm reading it — and of course, it being wordless, we can read it however we want to — it's like a completely different person he's now encountering. That he finally sees the clown as a baby, or a little child.MF: I am so glad that's how it struck you. Because to me that spread was the pivotal moment in the book.

RS: It's huge. Completely unexpected.

MF: The thing that freaks me out about clowns is that they look a certain way, and they maybe act a certain way, but that doesn't mean they necessarily feel a certain way. Underneath it all there might be something else going on. That's true about everybody at times in our lives, and I wanted it to be a revelation about the farmer as well. This obviously isn't what he expected his evening to be like.

RS: Right, and the farmer transforms from being dutiful to actually having an emotional stake in this child.

MF: I was originally thinking maybe it would take a few days for the circus train to come back, so there would be more time for their relationship to deepen and change. But there were issues about that, because I wanted it to be a real child who's lost and scared. Once the child and the farmer got too comfortable with each other, a couple days in and we'd have a different relationship, and that wouldn't work.

RS: It seems like you need to have either a 32-page picture book or a 148-page novel.

MF: Yes.

RS: I think you chose wisely.

MF: Thank you.

RS: You talked about the emotional engagement that brings you into a book, but then how do you create that emotional engagement for the reader? Or do you just cross your fingers and trust they're going to have the same feelings you do?

MF: I don't just cross my fingers. But I feel like that's the big question when it comes to illustration — how do you convey emotion in a picture? Not only over the span of the book, but in each individual image, each spread. What are you trying to say emotionally, and how do you show that emotion? An incredible book that has inspired me on that topic is Molly Bang's perception and composition book Picture This.

RS: That's a great book.

MF: I also think of Trina Schart Hyman's image on the back of the jacket of her Little Red Riding Hood, where she's leaving the forest. It's an incredible example of how the emotion of a scene can hit before the content does. We feel relief that this character — who we may not even see at first as Little Red Riding Hood — is leaving a dark and oppressive place. And then we start to see the elements. Oh, it's Little Red Riding Hood. Oh, it's the woods. Oh, it's the village. I think she was trying to build the image so the emotion hits first. You feel either the loneliness or the joy first, and then you start reading the picture — ah! The emotion kind of smacks us, the viewer, before our brain engages. That's something I aspire to. I don't always get there, but I'm always trying to get there.

RS: Well, you certainly do here. Your ending is a killer. You pull us in with a warmth that keeps increasing as the book goes, but when we get to the end we realize, "Oh my god, these two are going to part." It's horrible!

MF: I know. In an early dummy, I had the farmer on page 32 walking toward us with the clown hat on, kicking up his heels, but that was not a true moment. This is not how he would feel. So I started to draw how I thought he would really feel, which was devastated, and I thought, "This is just a real downer." It took a while to get to the idea of that monkey. I hope it feels somewhat inevitable, but it really did take a lot of soul-searching to figure out the feeling I wanted to leave this farmer with. I didn't want it to be a devastating story.

RS: And it would be, without that monkey. The way the monkey is looking out at us and telling us, "Don't tell the farmer I'm behind him," pulls us into the story, so we feel like we're part of something.

MF: That's really important to me, because I wanted the reader to be part of the understanding of these two characters. It's one of the reasons the book is wordless. I wanted us to perceive the characters a certain way, and to realize over time, after reading the book, that our perception was skewed as well, as maybe the farmer's initially was toward the clown. We don't know exactly how the clown perceives the farmer, but that was an element too.

RS: With the clown — you're really honest about how a child would be when he realizes his family's coming back. The long spread with the two of them and the approaching train, toot-toot, up there in the corner, where the clown is jumping up and down, and he's all excited, and the farmer is protectively holding his hand, and watching out for him, making sure he doesn't run onto the tracks, but the emotion of the kid, who's so — you know, they don't think about other people's feelings, really.

MF: Right.

RS: And he's just excited: "My parents are back!" But in the farmer's posture, and in his little dot eye, you can see the sadness of the impending separation. Then the clown gives him a gift. He races back to say goodbye to the old man. And there's that beautiful hug. And then they kiss. And I'm going to start crying.

When I look at wordless books today, they seem to mostly be becoming more and more elaborate. And this book is really stripped-down.

MF: I didn't set out to do a wordless book. I set out to tell a particular story, and as I was telling it I realized it would be more powerful without words. It's about impressions and misunderstandings of appearances. You get a slow understanding of who these characters are based on their behavior. I don't necessarily think there was a whole exchange of language between these two. It was more about how they were acting with each other, and for me that was somewhat of a wordless exchange. This paring-down was how I arrived at doing the book in a wordless way.

RS: Did you create any kind of a text at all?

MF: In the very beginning I wondered if there should be one, but no, not really. That's not unusual for me. When I did the book Roller Coaster I drew it out in thumbnails without words, and then the words came at a later point in the process. I think I was expecting that to happen with this book, and then I realized it wasn't going to. I truly didn't set out to do a wordless book, although I love them, sometimes.

RS: Sometimes they feel too much like a puzzle, on purpose. The challenge is to figure out what's going on. Whereas this, to me, is more immediate: you don't have to work at deciphering the action, which allows you to just become invested in these characters and their situation. There's no plot puzzle to solve here.

MF: I first came up with these two characters then wondered: How did they end up being in the same place, holding hands like this? As I was thinking about it, it almost offered a little film to me. The beginning pages of the book were very clear, to the point where the farmer walks across the field and sees that clown.

RS: The farmer kind of looks like the long arm of the law as he's approaching.

MF: And I thought, "I have to get this down on paper. I don't want to lose it. But I don't know what's going to happen after this moment." So I worked on thumbnails and little dummies, trying to nail down the story so it didn't disappear. There's something about it operating like a film but then having to freeze. I love animation, and I'm very inspired by it. Sometimes I think certain ideas that I'm playing with would be better done as animation than in a picture book, where you have to choose that exact moment to portray. And you have the page turn, which is unique to the picture book — it's such an incredible tool, but it can sometimes get in your way. I always spend a lot of time in those initial explorations trying to figure out: is this form the right form for this story to be in, and if so, how do I tell it? I feel like those initial explorations are really the architecture. I think that's why I said in the beginning it takes time. I can't imagine doing it any faster. Because some of those realizations just take so long to come to me. It's not immediate.

RS: You just have to let them wander around in your head for a while.

MF: I do. This book was very dreamy. Once I had the picture story in place and it was just a matter of executing it, it was also a really dreamy experience for me to sink into the actual time of making the pictures. The world was so spare.

RS: It's a very dreamy landscape as well.

MF: Thank you. I really wanted it to feel like that. That's how I was feeling about it. There's just something about those two characters being so by themselves, in their own world for that short time

RS: It's kind of amazing when you think about what we can get away with in picture books. If you just described this situation — a child gets tossed off a train, in the middle of the desert, and there's this old man, and he comes and takes the child to his house.

MF: Trust me, I know. Those closest to me will ask, "What are you working on?" and I'll say something like what you just said, and they'll say, "Oh my god. Are you serious?"

More on Marla Frazee from The Horn Book

- "Why We're Still In Love with Picture Books (Even Though They're Supposed to be Dead)"

- "Color Commentary: I’m Not the Boss of Them"

- "Sight Reading: Something Old, Something New: Marla Frazee’s Picture Book Art"

- Select Horn Book reviews of books by Marla Fraze

- "Marla Frazee, wipe that smile off your face!" Talks with Roger outtake

Sponsored by![]()

says

Add Comment :-

RELATED

RECOMMENDED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.