Jodi Lynn Anderson Talks with Roger

Talks with Roger is a sponsored supplement to our free monthly e-newsletter, Notes from the Horn Book.

Talks with Roger is a sponsored supplement to our free monthly e-newsletter, Notes from the Horn Book. To receive Notes, sign up here.

Sponsored by![]()

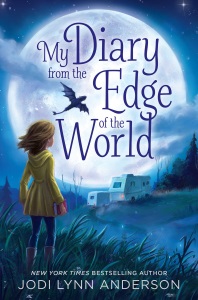

Ambitious but light-handed, My Diary from the Edge of the World is the story of twelve-year-old Gracie, whose family is being threatened by an ominous Cloud, sending them on a road trip to the edge of the world. Literally: while Gracie's world is much like our own, it is also flat. My conversation with Jodi Lynn Anderson (author also of the May Bird trilogy and several books for young adults) turned decidedly cosmic as we explored the Big Questions her novel is unafraid to address.

Ambitious but light-handed, My Diary from the Edge of the World is the story of twelve-year-old Gracie, whose family is being threatened by an ominous Cloud, sending them on a road trip to the edge of the world. Literally: while Gracie's world is much like our own, it is also flat. My conversation with Jodi Lynn Anderson (author also of the May Bird trilogy and several books for young adults) turned decidedly cosmic as we explored the Big Questions her novel is unafraid to address.Roger Sutton: When creating an alternate world, how do you know how much you can do? How much can you change from our world? How much do you leave the same?

Jodi Lynn Anderson: I guess it comes down to choosing the story you want to tell, choosing what you want to focus on. You could go down a wormhole of different aspects for the world, which, in My Diary from the Edge of the World, is basically our world but tweaked.

RS: Right.

JLA: With this book it became a question of how many things did I want to tweak. When did those little changes contribute to the book's momentum and the character-building, and when did they take something away or slow things down?

RS: How much did you know about the world your characters were going to be in when you began?

JLA: Well, I'm a little bit obsessed with old nautical maps. A lot of times when I'm supposed to be working, I'm just Googling old maps, those ones that say "here be dragons," with drawings of mermaids and giant squids and all of those things. The idea for this book started with me thinking: what if those creatures imagined by the people drawing those maps had turned out to actually be out there? What effect would that have had on the way the world took shape? How would it have changed history? The big thing for me was the Industrial Revolution, and how wild beasts could have interrupted things.

RS: I think you did it with aplomb, to say that this major event that created our modern world didn't happen.

JLA: My idea was that the Industrial Revolution happened a little bit, but it got truncated, in some good ways and some bad ways. Everybody has some ambivalence about the Industrial Revolution, what benefits it brought and also what harm, so there's a little bit of that in there.

RS: It must have been difficult to do it with such a light touch, unless you're just one of those irrepressibly funny people — are you?

JLA: I'm pretty goofy. But Gracie is not really me. The first image I had of Gracie was this girl I knew at summer camp who would stand on a picnic table and have everybody throw Cheerios into her mouth. She was just this confident, attention-loving, irresistible person.

RS: Gracie's big sister accuses her of being a psychopath when it comes to seeking attention!

JLA: Yes. And there are many positives and downsides to that, and I wanted those both to be present in Gracie's personality.

RS: I really identified with Gracie when she's talking about writing in her diary and says, "I wonder that if you keep growing and changing like you're supposed to, if you always end up embarrassed about how stupid you used to be." I feel that all the freakin' time.

RS: I really identified with Gracie when she's talking about writing in her diary and says, "I wonder that if you keep growing and changing like you're supposed to, if you always end up embarrassed about how stupid you used to be." I feel that all the freakin' time.JLA: Oh my god. That was definitely straight from my own personality, the best of myself.

RS: Did you write when you were a kid?

JLA: I did, but I was very, very private about everything. I was a quiet kid, and I was secretive about my writing, so I wrote a lot but rarely shared it with people. It just felt so personal and vulnerable. I shoved my notebooks under my bed. We moved from my childhood home when I was thirteen, and I buried my journals under a big boulder in the backyard. I went on to be an English major, and then I moved to New York and worked in publishing. That was where I was forced to share my work.

RS: What did you do in publishing?

JLA: I was an editorial assistant at HarperCollins to begin with, and then I worked at a book packaging company called 17th Street Productions [now Alloy Entertainment].

RS: Oh, they did those paperback series for teens.

JLA: They did, yeah. A lot of that job was sharing creative work and trying to develop ideas and do outlines. That was the first time I really had to expose my own work. It slowly built my confidence.

RS: What did you find that working on the other side of things in publishing did for your writing, or to it?

JLA: It taught me so much — especially about structuring stories — that I don't know that I ever would have learned on my own. On the other side, when I left to write for myself it took me a while to embrace my own quirkiness and weirdness. To not always think, "Who's going to read this?" but instead to trust that this is the story I need to write and that it'll find its audience. That was a challenge, coming from a world where I always needed to think of the audience as one of the primary factors.

RS: I think most publishing is a negotiation between what the author wants to say and what the audience wants to read. Books fall at different spots on that continuum, but both things are always in play.

JLA: It's true, and it's almost like a conversation I'm having with someone else. Maybe it's just that the longer anyone writes, the more they trust their own idiosyncrasies, and trust that somebody else will be able to connect with them. That's been the hardest and most rewarding growth for me as a writer over the years.

RS: One thing that can drive me crazy as a reviewer — and we get a lot of books like this — is when the main character is really just meant to be a stand-in for the reader, so it's kind of a generic kid's voice. Whereas in your book, Gracie really is an individual. She's a true character.

JLA: With Gracie, it was her personality from the start that drove so much of my outlining and structuring of the story. The story came more naturally that way. It was just a joy to sit down to write every day, because I felt like this character was in control, so there was always momentum.

RS: How much did you know about the ending of the story when you began? It's a great ending. I don't know how we can talk about it without giving it away, though.

JLA: The characters are searching for this world, and — actually, that's one major thing I didn't know. I didn't know whether they were going to find it or not, or how I was going to resolve that. I knew from the beginning how the loose ends of the family story tied up.

RS: Did you know how the — let's say vaguely — the business with the Cloud was going to work out?

JLA: I did. There was always this sense of finding acceptance. That is part of what Gracie's journey is about, not prevailing over something inevitable, but instead finding a different way of looking at the inevitable, and finding a way to incorporate it into her life.

RS: And how about the — how do we distinguish the two endings here? When they get where they're going, and they discover that they can't do what they thought they were going to do.

JLA: Right.

RS: As I was reading the book, I thought this must be the first in a trilogy. Because I'm looking at what I've read, and I'm looking at how many pages I have left, and I'm thinking they're not going to be able to do what they need to do here. Can we assume that this is the end of the story?

JLA: It is.

RS: Good for you, girl. I'm tired of these multi-volume things.

JLA: Yes. I've written a few books that had follow-ups, and also a trilogy. That's not where my head is at right now, and I just felt complete about this story.

RS: There's a scene at the end where Gracie's family gets to look at, but not touch, what might have been different for them. That was really powerful. Do you think alternative worlds are out there?

JLA: I do. I get a lot of comfort from reading about those kinds of things, and I think it's because it makes me feel as if time and reality have more meaning than what we can grasp. Especially with losing people. I find that idea extremely comforting.

RS: Did you have any thought about what actually happens to a person in the Cloud?

JLA: I think it's transformation, and what lies at the other side of the transformation is not all that relevant. Up until that moment of transformation, the idea of what is actually happening in the Cloud is subjective. That's why each person sees the Cloud differently, sees a different shape in the Cloud. But then once that threshold has been stepped over, that shape doesn't really matter so much. It's a change.

RS: I like to think that when it happens, we understand it at that moment, and recognize it.

JLA: I would like to hope that as well.

RS: How much of this book would you say is you exploring what you know, and how much is you finding out things that you want to know?

JLA: It's always so much of both. When I was twelve, my family moved from an idyllic little town in the northeast U.S. to Hong Kong. It was just me and my parents, and we were thrown together a lot.

RS: And in such a different world.

JLA: Exactly. A lot of that experience went into this book. Those dynamics of being in close quarters with your family was something I knew very well and was trying to revisit. And then on the other hand I'm always reaching toward things that I don't know. The longer I'm writing, the more certain I am that I'm leaving a lot of things unanswered. That's the most truthful way for me to end things. The book ties up in a lot of ways, but at the same time Gracie's left reaching toward all of her wants, and I think that's the way life is.

RS: I think that kind of an ending allows the character to stay in the reader's mind. You don't want to feel like everything's all wrapped up, because then you don't have to think about them anymore.

JLA: That's such a good point. I totally agree.

RS: It's different from not tying up a plot thread, which is annoying — when you finish reading a book thinking, wait a minute, she made such a big deal out of X. What happened with that? But I think you really crossed your ts as far as the structure of your book is concerned. To leave the characters wondering, or even grieving, is not a bad thing.

Sponsored by![]()

RELATED

RECOMMENDED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy: