Jennifer Donnelly Talks with Roger

Talks with Roger is a sponsored supplement to our free monthly e-newsletter, Notes from the Horn Book.

Talks with Roger is a sponsored supplement to our free monthly e-newsletter, Notes from the Horn Book. To receive Notes, sign up here.

Sponsored by![]()

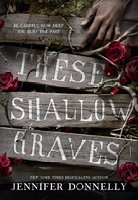

Fans of Jennifer Donnelly's first novel, A Northern Light, will enjoy her return to the Gilded Age in These Shallow Graves, a rich tale of murder and romance set in 1890 Manhattan. Plus: a fascinating presentation of early forensic medicine should draw in devotees of CSI and The Knick.

Fans of Jennifer Donnelly's first novel, A Northern Light, will enjoy her return to the Gilded Age in These Shallow Graves, a rich tale of murder and romance set in 1890 Manhattan. Plus: a fascinating presentation of early forensic medicine should draw in devotees of CSI and The Knick.Roger Sutton: I saw on your website that you said the idea for These Shallow Graves started with an image in your head of a dead man with a tattooed face. How did that turn into this hundred-chapter triple-decker of a novel?

Jennifer Donnelly: There's a bit of a backstory to it. I had written A Northern Light and Revolution, and both of those books had been inspired by ghosts. It's hard dealing with ghosts, because they sit in a room with you, and they keep you company for years, and they give you their stories, but they really do take pieces of your heart in exchange for that. I was very, very weary of ghosts. So I was working on a lovely Disney series about mermaids [The Waterfire Saga], and I was having a wonderful time, and this dead man shows up in my head. I had this sinking feeling, like "Oh no, here we go again." And then the other characters came. That's how it happens — they sort of walk out from my imagination. His story was intertwined with theirs, but most of all with this young woman, Josephine Montfort. I had to get to know these two characters the best, but they're very defiant and made me work hard to understand them, to coax the story out of them. It's a difficult question, and a difficult answer, and I end up sounding like a fruitcake.

RS: I want to ask a slightly theological question. When you talk about ghosts, how literal are we being?

JD: Well, for me it's not like a guy in a sheet howling in the corner of the room rattling chains, a green glow in a haunted house or anything like that. It is just a heaviness. It's a feeling.

RS: So where do you think the ghost came from in this book?

JD: It was this man. He just took up residence in my head. I haven't been able to dig deeper than that into my subconscious to figure out why. Maybe I was missing the past and history, the old streets that I like to walk down in London or Paris or New York — a kind of calling back to that.

RS: Now that it's done, are you surprised by the direction and shape the novel took? When you originally saw this vision of the man with the tattooed face, is this the book you thought it would be?

JD: It is. I knew he didn't get in that coffin of his own free will. There was a dark story behind him, how he died, why he was lying in his coffin, why he had the tattoos. I knew there was something sinister about it. I'm not surprised at all that it took the shape of a murder mystery. A guy in a coffin pops up in your head, it's never going to be good.

RS: There are a lot of elements going on here. It is a murder mystery, and there's also a whole CSI dimension.

JD: Right, with Oscar the forensic medical student. I've fallen in love with Oscar. Nothing can gross this guy out. He amazes me. I just adore him, and I want to find out how he progresses in life. Does he get together with the girl he likes so much? He has taken me on a journey into the history of forensics, and I'm finding out that I love it.

RS: I bet that research just begets more research.

RS: I bet that research just begets more research.JD: Yeah, and it's so much fun. If there were no such thing as a deadline, I would still be researching. It's so compelling. It feeds the story. What you uncover helps you enrich characters and think up new storylines. Story and research are very interconnected for me.

RS: Your book had me go read Nellie Bly's Ten Days in a Mad-House. It's fabulous.

JD: It's amazing. And to think that she was brave enough to do that. She faked this whole breakdown, got herself committed, and wrote about it. She must have known to some degree what she was getting herself into, that it was going to be extremely challenging, dangerous. She actually changed policy, got money directed to the asylums, and changed the way people thought about these institutions and their patients. What a brave young woman.

RS: I think what amazed me most was her resolution that once she was in there she wasn't going to do anything to act crazy. She was simply going to reiterate that she didn't know who she was, but otherwise be completely rational, and that just made her seem crazier to them.

JD: You couldn't talk your way out of it once you were inside. It's terrifying to consider.

RS: I was really worried for your heroine, Jo. I don't want to give away too much of the story, but—

JD: Yeah. Near the end?

RS: Yes.

JD: If you were, I've done my job. I'm very happy about that.

RS: How do you make a Gilded Age heroine like Jo both true to her time but relatable enough to a contemporary young reader?

JD: I just let Jo speak. She is who she is. She is of her time, but she is a strong-spirited person. She's questing and she's restless. She's extremely curious and intelligent. I think you let that character speak, but you also show the stumbles that somebody like that makes as she tries to express herself and grasp what she's reaching for. She's so torn, and with good reason. She comes from a background where there's money, privilege, enough to eat, and there's a lovely life waiting for her if she marries Bram.

RS: Right, Bram's a good guy. It's not like he's the evil rich suitor contrasted against Jo's other man, the upright young journalist Eddie.

JD: Yes, absolutely. He's fantastic. I love Bram. There's nothing horrible about him at all, so it's a true, realistic, difficult choice for her.

RS: You've left a lot for us to wonder about, with her friend, Fay, who goes to Winnetka, and with Jo herself. What will happen to them next?

JD: It's very open-ended.

RS: What's your feeling about sequels?

JD: I would love to do one; we have to see if readers embrace the story. I want to know what happens with Jo. I can only imagine the sorts of challenges and sexism she would come up against as a young female reporter at that time. I'm curious to see what happens with her and Eddie. I want to find out what happens with Fay, and I really want to follow Oscar through the morgue and the streets of New York and see what kind of trouble he gets into.

RS: Oscar could have his own TV show. I think he should branch out.

JD: Absolutely. Why not?

RS: You've written a few historical novels for teenagers and a fantasy series for slightly younger kids as well as books for adults. Do these feel different to you as you write them?

JD: They share similarities. Writing any book is desperately hard for me, so that struggle is common to all the books. But besides that, I'm very aware of the openness of children, their vulnerability. For The Waterfire Saga — my mermaid books — I didn't want much bad language or too many racy scenes, that sort of thing. The message had to be clear and the plot had to be strong and engaging, because kids of that age will get frustrated if you don't get to the point. I feel like I can take a little more time and ramble around a bit more in my YA and adult books. But the commonality among all of them (other than being difficult to write) is that there's a lot of emotion. And hopefully a compelling plot. Hopefully there's something that will inspire the reader as he or she goes through the book as well.

RS: I was just thinking that if you did write a sequel to These Shallow Graves it could almost be published as an adult book. I wonder if that's ever happened before.

JD: That's a good question. I have no idea. Watching the characters get older…

RS: Right. Because this does seem to me to be a true crossover book. An adult would read this with no particular sense of "Oh, I'm reading a book for young people."

JD: I don't worry too much about those distinctions, because you can try to tell readers what to read and where to go in the bookstore, and they're going to do what they want to do. Readers will not be pigeonholed.

RS: Something I think you've done well in These Shallow Graves is to create a world for a reader to go into and wander around. We go uptown. We go downtown. Your characters are inhabiting a real place.

JD: I tried to make the city not just a setting but a character in its own right, someplace palpable that the reader can really orient herself within.

RS: We're having a mini-trend with this era, both in steampunk books and straightforward historical fiction. Often it's London, but some are set in the United States. I wonder if part of the reason is the parallels to our world today. We're in another Gilded Age, where some people are experiencing great wealth and luxury, and other people — most people — are not.

JD: What's going on in the world right now, the gulf between the haves and the have-nots — it almost feels insurmountable. Looking at the strides women have made, though, we've come such a long way. Jo didn't even have the vote. Working outside the home, for a woman of her class and station, was unthinkable. There is still wage disparity in the U.S. and so many issues, such as domestic violence, to be addressed. But then I think of places today where it's so dangerous just for a girl to want to go to school. I think your point is incredibly apt.

RS: Do you find that your novel overlays itself in your imagination when you visit New York now?

JD: Totally. That always happens. I can see an old building or an old facade or an old railing, and standing across the street from it, I just squint my eyes, and suddenly it's back a hundred years, and the person walking out of it is dressed like a Victorian. But certain types endure as well, and you see them today moving along the sidewalks. It's ghosts all over again. And the fact that the city is trying to pave itself over as fast as it can, and build itself up, and yet it can never escape its past. I like this contrast. I like living in that space between them as a writer.

Sponsored by![]()

says

Add Comment :-

RELATED

RECOMMENDED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.