Benjamin Alire Sáenz Talks with Roger

Talks with Roger is a sponsored supplement to our free monthly e-newsletter, Notes from the Horn Book.

Talks with Roger is a sponsored supplement to our free monthly e-newsletter, Notes from the Horn Book. To receive Notes, sign up here.

Talks with Roger is a sponsored supplement to our free monthly e-newsletter, Notes from the Horn Book. To receive Notes, sign up here.Sponsored by![]()

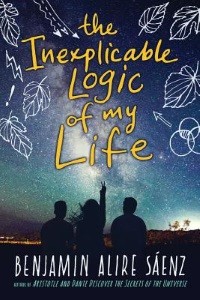

Vicente is the only parent Sal(vador) has ever known. Sal's biological father is a mystery; his mother, Alexandra, died when Sal was three; Vicente was his mom's best friend. But now there is a letter from Alexandra for Sal that she left with Vicente. I will not spoil the story by saying what was in it (although, beware, this conversation is not spoiler free!), but I will tell you that it is just one of the cries from the heart The Inexplicable Logic of My Life explores.

Roger Sutton: While reading your book I thought, I really want to date this dad, Vicente. He is completely perfect.

Benjamin Alire Sáenz: He is who I want to be. Not who I am, but who I would like to be. I do that with all of my characters. They have one of the flaws I have, and I zero in on that flaw.

RS: Is it smoking? Are you a smoker?

BAS: Yeah, I am. It's terrible.

RS: I wanted a cigarette the entire time I was reading the story.

BAS: I quit smoking. I quit twice a year. When my sister died, I started again. I'll quit again, but there's always this thing in me. I think writing books is a way for me to work out certain issues. I write about what matters to me, always. For instance, in this book, I really wanted to focus on family. We have this huge discourse on family in this country, but no one deconstructs it the same way. People talk about "the American family." The right wing has this thing — Focus on the Family. What the hell is that? I don't want to just discuss the issues — I want family to be a real part of the character of the novels I write, and I don't like to write things that feel like issue books.

RS: Yes, this is not a one-thing book.

BAS: There are a lot of things I talk about in this novel that are part of the novel. Family, God, faith, and even the idea of friendship — how men and women who are straight don't really think they can be just friends. But gays like me — I have a lot of women friends. If I were straight, would that happen? It would be nice if society would allow that to happen. So, I enjoyed, in the friendship between Sal and Sam [Samantha], examining a boy-girl relationship that was not romantic.

RS: I really liked the fact that you didn't use that as a narrative hook—will they or won't they?

BAS: Right. No, I never had that in my mind. Not ever. They were always going to be friends, and they'll love each other forever. I also wanted to deal with other issues those kids were facing. They had families. They were well taken care of, in a sense. Sam's mother Sylvia was not a good mother, but they weren't living in the streets, either.

RS: And you show love between them.

BAS: Absent parents aren't abusive per se. They're neglectful. They love in a very imperfect way. There are parents like that, and they do love their daughters and sons, but they're not parents in the way that we might think of it. And yet there are all kinds of parents in the world. In the book, there are the three parents: the good dad, the absent mother, and then the horrible mother who's a drug addict.

RS: Did you know you were going to kill four mothers in this book?

BAS: Actually, no. My editor brought that up. These things seem to happen to me. With my collection of short stories, people said there's not one lovable father in it. But in The Inexplicable Logic of My Life, I didn't do it on purpose. And yet I didn't change it when my editor alerted me because I thought that all of the deaths were necessary to the novel.

RS: They are. And it never felt like, oh God, there goes another one. But when I was done, I realized, oh my goodness. Four dead mothers.

BAS: Well, one of them was dead before the book started, so that doesn't really count.

RS: Okay.

BAS: I couldn't change the grandmother's death, because I wrote that as a tribute to my own mother who had died. My mother was very much like the grandmother, Mima, in the novel. Very kind. And she had a special relationship with my nephew who was adopted. I loved watching them, and I used that for this book. I wanted to talk about relationships between grandmothers and their grandchildren, and I wanted to write about my own mom. There's a line in the book that Vicente uses about his mother. He says, "If living is an art, your Mima is Picasso." I actually used that line at my mother's eulogy. And I wanted to pay tribute to her faith. I don't have her faith, but I wanted readers to understand some people do have that kind of faith, and it doesn't make them clichés.

RS: It seems to me like everybody in this book has faith of one kind or another. Do you share that with your characters?

BAS: Yes, I do. I'm an ex-Catholic priest. I have such a complex relationship to Catholicism. On the one hand, if I called myself a Catholic it would have to be a very unorthodox one, because I just don't believe all of the teachings of the Catholic Church.

RS: I'm the same way, but I think once you're born one, it's kind of hard to get away from.

BAS: But on the other hand, I'm an educated man because the Catholic Church educated me. It gave me something that is really important to me. So I always think about my faith. I always have it, and sometimes I can't talk about it, and sometimes I can. I am like an adolescent in that way. Teens are asking questions: who is God and what does it mean to have faith? That is part of the book, figuring out who you are, what do you believe in. I like the whole examination of the father-son dynamic. When the father's boyfriend comes into the picture, how does the son react? Sal probably thought it would be okay and cool, but he's really uncomfortable with it when it happens, frankly.

RS: You said that the father was who you wished you would be. How do you see yourself vis-à-vis Sal? How much of you is in him?

RS: You said that the father was who you wished you would be. How do you see yourself vis-à-vis Sal? How much of you is in him?BAS: I would say that I was like him in a lot of ways. I was, in my family, the good boy. I mean, I acted out in some ways, but I didn't know how to fight my way out of being the good kid. Sal uses his fists to fight out of it, but he doesn't really know that's what he's doing. He doesn't like that fighting role because he is a good kid. At the beginning of the novel he says that he feels like he's doing all of his living through Sam. Sam knows what she feels. She may be a drama queen, but she's alive. Sal is the kind of kid who is more comfortable with safety, and yet a part of him wants to be more alive. And he doesn't know how to do that, because he thinks the only way to do it is by being the bad boy, which he can't really be.

RS: Is that where you think Sal's punching comes from?

BAS: I do. He realizes that he punches people because he feels so strongly about the people that he loves. It's so visceral. And he's also fighting against a stereotype of the good boy, something he does and doesn't want to be. He knows he's afraid. Ultimately, that's it. His anger does not come out of hate. It comes out of fear. He's facing the unknown, and he's never had to do that before. Unlike people who have always faced the unknown, someone like his friend Fito.

RS: Fito is much more comfortable in his own skin than Sal is.

BAS: Yes. He's very aware. He has to be, because he spends so much time on the streets. He knows what he needs to do to survive, and why. Sal has never had to be that aware. He doesn't have those skills. So in that way, he doesn't know himself. It's also because Fito is gay. Coming to terms with that, he's had to be a lot more aware of himself.

RS: Who were these characters when you began, and who were they when you finished? Was there a difference?

BAS: Yes. Not Sal — I pretty much had him down. He is a kid who loved the world as it was, and he falls apart when it changes, because he doesn't know how to deal with that. But Sam, yes. Something that had not occurred to me until I was actually writing the story is that Sam becomes a woman over the course of the novel. She learns to carry herself with a kind of grace that she lacks at the beginning. She begins to have some discipline in life, starting with her mother's funeral. She takes charge of her own grief, and she changes because of that.

RS: What do you see of yourself in Sam?

BAS: Oh, I'm more like Sam than I'm like Sal in some ways. I'm effusive. I like to talk about my feelings, or at least express them, and not always appropriately. I don't shut up about things. And also, Sam really didn't like the mother that was given to her. She would have liked to have another kind of mother. And I felt like sometimes I would have liked another kind of father, though I loved my mother just the way she was. She was great.

My father was kind of difficult, and I really had to come to terms with who he was, and that he wasn't going to be anybody different. And because I did that, I enjoyed him, actually. I appreciated the kind of man he was, and I accepted his limitations. He was one of the most politically intelligent men I've ever met. He gave me my politics, and they were good politics. I always say that young men and women come of age when they look at their parents and see them not only as their parents but as people. They gain a lot of compassion, and it's easier to accept their flaws. Sam loved her mother, but she didn't like her.

RS: There certainly was something more to that relationship than what Fito had with his mother, for example. That was just a horror show.

BAS: Yes.

RS: I like the way Sal grows up at the end, too, when he agrees to spend time with Dad's boyfriend. It's what you were saying just now. He realizes that his father is a human being, apart from being his dad.

BAS: It's a complex thing when you're writing a novel, because so much of it is conscious and planned and deliberate, and so much of it is not, and it has to be a dance between the conscious and the unconscious. I bring my best instincts to my work. For instance — and I come by this naturally, or I think I do — I am a very good judge of character.

RS: How am I doing?

BAS: You're doing very well.

Sponsored by![]()

RELATED

RECOMMENDED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy: