A Year with Words and Pictures — but No ALA Annual

Who are we this time of year, without the organizing principle of the various celebrations of books and authors at ALA Annual? Usually, we’d be looking forward to the Coretta Scott King (CSK) Book Awards Breakfast, the Newbery-Caldecott-Legacy Banquet, the Pura Belpré Celebración; running into old friends on the exhibit hall floor; making new friends among our fellow children’s book enthusiasts; and so much more.

Who are we this time of year, without the organizing principle of the various celebrations of books and authors at ALA Annual? Usually, we’d be looking forward to the Coretta Scott King (CSK) Book Awards Breakfast, the Newbery-Caldecott-Legacy Banquet, the Pura Belpré Celebración; running into old friends on the exhibit hall floor; making new friends among our fellow children’s book enthusiasts; and so much more. In lieu of the traditional conference, ALA will hold a virtual event from June 24 through 26, and some of the acceptance speeches, including Newbery, Caldecott, CSK, and Legacy, will be premiered virtually throughout the day on June 28. (See ala.org for more information.) So this issue of the Magazine has somewhat more improvisational coverage than usual, including a few new elements to fill in the gaps (or what we thought might be gaps), to provide a snapshot of this unprecedented ALA Youth Media Awards (YMA) year.

Generally as we’re getting the July/August ALA-themed special issue together, we find ourselves counting on our fingers a lot, trying to remember just how many speeches and profiles we are shepherding into print. This year the counting was less straightforward: “Oh, wait. The same book won the Newbery and the CSK Author Award. And another book won both the CSK Illustrator Award and the Caldecott Medal (and a Newbery honor). Surely this is a first.” It’s times like these when we miss the late Peter Sieruta, who could have told us in a second how much of a novelty this double-Gemini constellation is. Just two individual titles — New Kid and The Undefeated — won a combined four of the top awards! And both winners are African American men; in the twenty years since Christopher Paul Curtis won the Newbery Medal, only two men of color — Kwame Alexander and Matt de la Peña — have done so, and only a very small handful before that. (Not Walter Dean Myers?! you ask; nope. Though men of color are better represented among honor recipients.)

Generally as we’re getting the July/August ALA-themed special issue together, we find ourselves counting on our fingers a lot, trying to remember just how many speeches and profiles we are shepherding into print. This year the counting was less straightforward: “Oh, wait. The same book won the Newbery and the CSK Author Award. And another book won both the CSK Illustrator Award and the Caldecott Medal (and a Newbery honor). Surely this is a first.” It’s times like these when we miss the late Peter Sieruta, who could have told us in a second how much of a novelty this double-Gemini constellation is. Just two individual titles — New Kid and The Undefeated — won a combined four of the top awards! And both winners are African American men; in the twenty years since Christopher Paul Curtis won the Newbery Medal, only two men of color — Kwame Alexander and Matt de la Peña — have done so, and only a very small handful before that. (Not Walter Dean Myers?! you ask; nope. Though men of color are better represented among honor recipients.)

After the announcement, one of our Facebook followers tongue-in-cheekily wondered whether we even still need the Newbery and Caldecott, since the CSK awards have been covering so much of the same ground. This recalls another perennial debate: “Do we still need identity-based awards?” (Short answer: yes.) This isn’t the first time the Newbery and CSK winners have been the same — remember Christopher Paul Curtis’s Bud, Not Buddy in 2000; and in 2017 Javaka Steptoe won the Caldecott and CSK Illustrator Award for Radiant Child, for example. But gone in 2020 is an all-white slate of awardees. All but one of the Newbery winners are people of color; all of the Caldecott winners are people of color. The Robert F. Sibert and Theodor Seuss Geisel medalists are also people of color. These are welcome firsts.

A not-so-welcome observation is about gender. The lack of recognition for women artists, especially, in our field continues to confound. Of the illustration awards (Caldecott, CSK Illustrator, and Belpré Illustrator), only LeUyen Pham (Caldecott honoree), Vashti Harrison (CSK Illustrator honoree), and April Harrison (CSK/John Steptoe New Illustrator winner) — who are all women of color — were recognized. 2018’s lineup of award-deserving women picture-book creators was close to historic (with Sophie Blackall the 2019 Caldecott winner and such creators as Yuyi Morales, Jillian Tamaki, Grace Lin, Laura Vaccaro Seeger, and more as strong contenders). Though this year’s field of eligible titles did not impose the same expectations, still…why does the Caldecott continue to reward male artists in such skewed numbers and so consistently? Since it’s a question we ask every year, there may not be an answer — but we need to keep asking. (For an in-depth look at this and related questions, seek out the work of KidLitWomen* — one of whose founders, Karen Blumenthal, passed away in May; see obituary on page 163.) Women creators do tend to fare better in writing awards, as A.S. King did this year with her astounding Printz Award–winning novel Dig.

Happily, this year’s Caldecott-winning picture books were not just by people of color, they also (mostly; Bear Came Along being the exception) featured people of color in the illustrations — an important point of visibility given the disheartening statistic about picture books featuring exponentially more white people, animals, and nonhuman protagonists than people of color. Other observations about this year’s Caldecott winners: our own mock Calling Caldecott winner Saturday was shut out by ALA — but was awarded the 2020 Boston Globe–Horn Book (BGHB) Award for Picture Book. There were no wordless books on the list this year. We’ve already lodged our objections (see Martha V. Parravano’s January/February editorial) to the citizenship/residency requirement wherein books such as Small in the City (which won Canada’s Governor’s General Literary Award and appeared on several best-of lists) and Birdsong (a BGHB honoree and American Indian Library Association, or AILA, honoree) are ineligible. We also can’t help wondering, given the Caldecott’s past recognition of the graphic novel This One Summer (2015) and illustrated novel The Invention of Hugo Cabret (2008), whether New Kid made to it their discussion table.

We know by now that 2020 is, monumentally, the first time a graphic novel has won the Newbery Medal, an award that has historically, deliberately, and pointedly divorced words from pictures in order to specifically recognize accomplishment in writing. Per the Newbery manual: “The committee is to make its decision primarily on the text. Other components of a book, such as illustrations, overall design of the book, etc., may be considered when they make the book less effective.” (“Less.” God forbid they help.) We also know that this is not how graphic novels work — it’s precisely the interplay between words and pictures that makes the story what it is. How did this year’s committee come to its decision? Did the committee members truly disregard New Kid’s art while considering its words? Were they even supposed to? Did they decide to put that requirement somewhat off to the side? The previous number of graphic novel Newbery honorees has been small-but-not-insignificant (and recent): Roller Girl (2016), El Deafo (2015). Is this a one-off or will we be seeing future Newbery committees recognizing graphic novels with this award?

What else is interesting about this year’s Newbery? A picture-book text, Kwame Alexander’s, was recognized with an honor — which we may think of as unusual but has been a fairly steady occurrence through the decades. And just since the picture book Last Stop on Market Street won the 2016 Newbery Medal, three picture book texts, all by men of color, have been recognized: honorees Freedom Over Me, Crown, and now The Undefeated. Other Words for Home broke ground as a contemporary, U.S.-set Newbery book with an identifiably observant Muslim protagonist — and it also added to the growing number of Newbery verse novels (starting with Out of the Dust, 1998). No historical fiction was recognized, so: no A Place to Belong; no Scott O’Dell winner Butterfly Yellow; no Indian No More (which won an AILA Award; see more of our venting about books that should have won in “Mind the Gap” on page 92).

What else is interesting about this year’s Newbery? A picture-book text, Kwame Alexander’s, was recognized with an honor — which we may think of as unusual but has been a fairly steady occurrence through the decades. And just since the picture book Last Stop on Market Street won the 2016 Newbery Medal, three picture book texts, all by men of color, have been recognized: honorees Freedom Over Me, Crown, and now The Undefeated. Other Words for Home broke ground as a contemporary, U.S.-set Newbery book with an identifiably observant Muslim protagonist — and it also added to the growing number of Newbery verse novels (starting with Out of the Dust, 1998). No historical fiction was recognized, so: no A Place to Belong; no Scott O’Dell winner Butterfly Yellow; no Indian No More (which won an AILA Award; see more of our venting about books that should have won in “Mind the Gap” on page 92).

This year’s Robert F. Sibert Informational Book Award committee made a delightfully bold and refreshing choice with its selection of Fry Bread as winner. To quote ourselves (“How Do You Solve a Problem like Nonfiction?” May/June 2020 issue): “It’s great that those who pick up Fry Bread looking for a good picture book will learn so much about a diverse and varied group of cultures who historically and systematically experience erasure; and it’s gratifying that those who look to the Sibert list for excellence in informational books will find this warmhearted storybook there.” Other Sibert honorees included Antoinette Portis’s picture book Hey, Water! and Lori Alexander’s middle-grade science biography All in a Drop; along with two books awarded by the Boston Globe–Horn Book committee: 2020 honoree Ordinary Hazards by Nikki Grimes; and 2019 winner This Promise of Change by Jo Ann Allen Boyce and Debbie Levy. A few worthy titles not named by the Sibert were recognized by other awards: Barry Wittenstein’s and Jerry Pinkney’s A Place to Land with NCTE’s Orbis Pictus Award; Deborah Heiligman’s Torpedoed with SCBWI’s Golden Kite Award (also a finalist for the YALSA Award for Excellence in Nonfiction for Young Adults, the winner of which was Free Lunch by Rex Ogle); Ashley Bryan’s Infinite Hope was a CSK honoree and BGHB winner.

This year’s Robert F. Sibert Informational Book Award committee made a delightfully bold and refreshing choice with its selection of Fry Bread as winner. To quote ourselves (“How Do You Solve a Problem like Nonfiction?” May/June 2020 issue): “It’s great that those who pick up Fry Bread looking for a good picture book will learn so much about a diverse and varied group of cultures who historically and systematically experience erasure; and it’s gratifying that those who look to the Sibert list for excellence in informational books will find this warmhearted storybook there.” Other Sibert honorees included Antoinette Portis’s picture book Hey, Water! and Lori Alexander’s middle-grade science biography All in a Drop; along with two books awarded by the Boston Globe–Horn Book committee: 2020 honoree Ordinary Hazards by Nikki Grimes; and 2019 winner This Promise of Change by Jo Ann Allen Boyce and Debbie Levy. A few worthy titles not named by the Sibert were recognized by other awards: Barry Wittenstein’s and Jerry Pinkney’s A Place to Land with NCTE’s Orbis Pictus Award; Deborah Heiligman’s Torpedoed with SCBWI’s Golden Kite Award (also a finalist for the YALSA Award for Excellence in Nonfiction for Young Adults, the winner of which was Free Lunch by Rex Ogle); Ashley Bryan’s Infinite Hope was a CSK honoree and BGHB winner.

The Geisel continues to push the envelope, as Tom Wolfe put it, perhaps more than any other ALSC award. This year, it would be hard to categorize any of the winners as a traditional I Can Read–type easy reader. Geisel committees seem to be gravitating to less traditional formats and presentations, with an emphasis on dialogue-heavy texts (especially speech bubbles) and on humor. Seriously, if you are looking for a funny book, head for the list of Geisel winners, including this year’s medalist Stop! Bot! We would have loved to have seen Kevin Henkes’s latest Penny book, Penny and Her Sled, on the Geisel slate, though — and incidentally, its theme of waiting is especially relevant in these COVID-19 times — but we’re thrilled that Henkes won the Children’s Literature Legacy Award.

The Geisel continues to push the envelope, as Tom Wolfe put it, perhaps more than any other ALSC award. This year, it would be hard to categorize any of the winners as a traditional I Can Read–type easy reader. Geisel committees seem to be gravitating to less traditional formats and presentations, with an emphasis on dialogue-heavy texts (especially speech bubbles) and on humor. Seriously, if you are looking for a funny book, head for the list of Geisel winners, including this year’s medalist Stop! Bot! We would have loved to have seen Kevin Henkes’s latest Penny book, Penny and Her Sled, on the Geisel slate, though — and incidentally, its theme of waiting is especially relevant in these COVID-19 times — but we’re thrilled that Henkes won the Children’s Literature Legacy Award.

Last year was the first year that the YMAs included select affiliate awards — the Asian Pacific American Librarians Association (APALA) Literature Award, the Association of Jewish Libraries’ (AJL) Sydney Taylor Book Award, and the American Indian Library Association (AILA) Youth Literature Award. Because of AILA’s frequency of awards (every two years), this was the first Midwinter where the group’s winning books were actually announced during the press conference — and what a great, diverse year for Native #OwnVoices authors. Winners are named in three categories — Picture Book (winner: Bowwow Powwow: Bagosenjige-niimi’idim by Brenda J. Child; translated into Ojibwe by Gordon Jourdain; illustrated by Jonathan Thunder); Middle Grade (winner: Indian No More by Charlene Willing McManis with Traci Sorell); Young Adult (winner: Hearts Unbroken by Cynthia Leitich Smith). All told, including honor books (five for picture book, two for MG, four for YA) and the Sibert Medal, this year’s winners represented a wide variety of Native voices, backgrounds, and experiences. From committee chair Lara Aase (in AILA’s press release): “Many of us grapple with issues of identity; we are grateful to see authors and illustrators represent the myriad identities of young Indigenous readers.”

In the past few years, a number of major publishers have launched imprints focused specifically on publishing diverse books, and this year’s awards show those imprints off to a strong start. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt’s Versify imprint published the multi-award–winning The Undefeated; as well as Pura Belpré Illustrator Honor Book ¡Vamos!: Let’s Go to the Market by Raúl the Third; and Sydney Taylor Honor Book Anya and the Dragon by Sofiya Pasternack. Disney-Hyperion’s Rick Riordan Presents, which publishes #OwnVoices books inspired by the mythology and folklore of underrepresented groups, produced Pura Belpré Author Award winner Sal and Gabi Break the Universe by Carlos Hernandez, and CSK Author Honor Book Tristan Strong Punches a Hole in the Sky by Kwame Mbalia. Penguin’s Kokila imprint published Pura Belpré Illustrator Honor Book My Papi Has a Motorcycle, illustrated by Zeke Peña, written by Isabel Quintero; Schneider Family Book Award Honor Book Each Tiny Spark by Pablo Cartaya; and AILA Picture Book Honor Book At the Mountain’s Base by Traci Sorell, illustrated by Weshoyot Alvitre. From Random House’s Make Me a World imprint, Pet by Akwaeke Emezi was a Stonewall Honor Book; and Salaam Reads, Simon & Schuster’s imprint focused on books with Muslim characters, published APALA Honor Book Bilal Cooks Daal by Aisha Saeed, illustrated by Anoosha Syed.

This is all good news regarding the diverse books conversation — and especially now, given the precarious state of the industry due to COVID-19, it would be a good time to put our money where our mouths are by supporting publishers committed to inclusive representation, including small and independent presses. Same, too, with independent bookstores that may be struggling right now — spend some money at the indies, if you can (and see also our recent online article “Books Beyond Buildings”). We hope you stay healthy, and we hope to see you — in person or virtually — at Midwinter 2021.

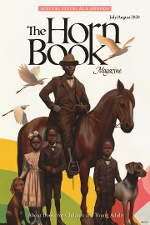

From the July/August 2020 issue of The Horn Book Magazine: Special Issue: ALA Awards. For more speeches, profiles, and articles, click the tag ALA 2020.

Single copies of this special issue are available for $15.00 including postage and may be ordered from:

Single copies of this special issue are available for $15.00 including postage and may be ordered from:

Kristy South

Administrative Coordinator, The Horn Book

Phone 888-282-5852 | Fax 614-733-7269

ksouth@juniorlibraryguild.com

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!