2018 School Spending Survey Report

Lift Every Voice: Necessary Foundations

The sound of her voice.

The sound of her voice. The comfort of her lap. The colors and words on the pages of the books tucked around us. My mother read to me from the time I was born. I vaguely remember a poem called “The Rock-a-By Lady.” I found out later it was by Eugene Field, but at the time it didn’t occur to me that someone had to write those magical words that my mother would whisper to me each night.

The sound of her voice. The comfort of her lap. The colors and words on the pages of the books tucked around us. My mother read to me from the time I was born. I vaguely remember a poem called “The Rock-a-By Lady.” I found out later it was by Eugene Field, but at the time it didn’t occur to me that someone had to write those magical words that my mother would whisper to me each night.When I got a little older, Mom would take me to the huge brick library on the corner. It was built like a castle, and treasures were nestled inside. I was allowed to check out ten books each week. I read them all, then checked out ten more the following visit. By the time I was eleven, I had read all the books on the elementary side of the library. I continued to inhale books as I sailed through school, more interested in reading than writing anything. I didn’t know it then, but I was filling my brain with thousands of words and images and thoughts, the necessary foundation for what was to come.

Looking back, although I was unaware of it at the time, I had never read a book with an African American protagonist. It never even occurred to me that there could be one. Our school readers used Dick and Jane, Alice and Jerry — white children who lived in a lovely suburb — as our role models. And at the time I did not question it. I was encouraged to be an outstanding student and not make waves. My parents protected me with strong arms of love and strict standards of decorum.

Finally I found a book called Mary Jane by Dorothy Sterling, a story of a Black girl who suffers discrimination in elementary school. The writer wasn’t African American, but the girl on the cover of the book certainly was. I was intrigued and delighted. I gradually found a few more books by Black writers, but, to be honest, the library on the corner didn’t stock a lot of them.

Finally I found a book called Mary Jane by Dorothy Sterling, a story of a Black girl who suffers discrimination in elementary school. The writer wasn’t African American, but the girl on the cover of the book certainly was. I was intrigued and delighted. I gradually found a few more books by Black writers, but, to be honest, the library on the corner didn’t stock a lot of them.By the time I finished high school, I’d read thousands of books and could read novels in French without difficulty. Still, there were very few novels that featured Brown protagonists. I discovered poetry. Langston Hughes was amazing. Paul Laurence Dunbar was born in Ohio like me! And Zora Neale Hurston wrote with passion about subjects my mother probably would not approve of.

It wasn’t until my senior year of college that my advisor offered me the chance to study anything I wanted. I chose Black poets and writers. In that semester I finally got caught up with all I’d missed, all the books I hadn’t even known existed. It was exhilarating and empowering.

I taught high school English for twenty-five years, covering the requirements of Shakespeare and Wordsworth and Hawthorne and company, but also opening windows to my students so they could feel the breezes of Maya Angelou and Claude McKay and Ernest Gaines.

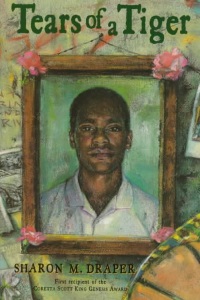

I’d been teaching for many years when I finally decided to write a book. I had zillions of words in my head. And I knew my audience — the teenagers in my classroom. Tears of a Tiger was released in 1994, and when I received the call telling me it had won a CSK Award, I didn’t even know such awards existed. I was thrilled, overwhelmed, and ecstatic. And very, very grateful. I have received a nod from the CSK five times now, for books that have reached young people the way those early books touched me. That thought still brings me to tears. I will always be grateful to the accomplished awards juries, to the Lord, and to my mother, who is ninety-three and still a lover of a good story!

I’d been teaching for many years when I finally decided to write a book. I had zillions of words in my head. And I knew my audience — the teenagers in my classroom. Tears of a Tiger was released in 1994, and when I received the call telling me it had won a CSK Award, I didn’t even know such awards existed. I was thrilled, overwhelmed, and ecstatic. And very, very grateful. I have received a nod from the CSK five times now, for books that have reached young people the way those early books touched me. That thought still brings me to tears. I will always be grateful to the accomplished awards juries, to the Lord, and to my mother, who is ninety-three and still a lover of a good story!From the May/June 2019 Horn Book Magazine: Special Issue: CSK Book Awards at 50. Find more information about ordering copies of the special issue.

RELATED

RECOMMENDED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!