Different Drums: Embracing the Strange

The Horn Book Magazine asked Kristin Cashore, "What's the strangest children's book you've ever enjoyed?"

“So very annoying, this volcano,” says Moominmamma with a sigh, flicking soot from her (substantial) nose and thinking of the nice new washing she’s hung out.

The Horn Book Magazine asked Kristin Cashore, "What's the strangest children's book you've ever enjoyed?"

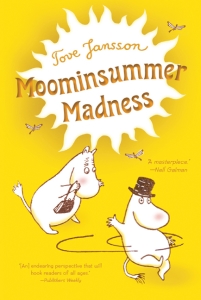

“So very annoying, this volcano,” says Moominmamma with a sigh, flicking soot from her (substantial) nose and thinking of the nice new washing she’s hung out. And it is annoying, as are the associated earthquakes and the flood wave that in Tove Jansson’s Moomin-summer Madness finally inundates Moominvalley and leaves an entire society of Moomins and other odd creatures bereft and homeless.

Strange, eerie, frightening things happen regularly in Moominvalley. Children are separated from parents, innocents are thrown into jail, families lose their homes to floods; the world is populated with malicious and unhappy people. But the Moomins move calmly along, implicitly trusting in one another’s (questionable) competence, feeding and comforting the malicious and unhappy, loving each other, embracing the strange. Says Moominmamma while admiring her golden bracelet, glimmering at the bottom of a pool, “We’ll always keep our bangles in brown pond water in the future. They’re so much more beautiful that way.”

There is the most beautiful, and beautifully restrained, joy in this odd little book, constantly about to tip over into something too strange and frightening. Just when the water is about to cover the last bit of roof on which sit the Moomins and the outcasts they’ve collected, a theater floats by. Everyone clambers aboard, not knowing what a theater is, thinking they’ve found their new home. What a scary and delightful home it is! The floor spins around like a carousel. Bright colored lights illuminate the sitting room at random intervals. Doors stand alone with no rooms behind them, staircases end in mid-air, and the open ceiling area is filled with pictures you can pull down and put back up again. And of course, the entire structure floats along unpredictably, pushed to and fro by the flood waves, landing in a rowan forest, becoming unmoored again. “‘I like it here,’ said the Mymble’s daughter. ‘It’s just as if nothing really mattered here.’”

There is a sense, in this book, that nothing really matters; that in this most terrifying world, there is no point in fear. The lost will be found, or they won’t; the floodwaters will recede, or they won’t; the Misabel who is always overcome with tearful histrionics will discover that all along, she’s been meant to be acting tragedies on stage, and after that, she’ll be happy — or she won’t. Most importantly, within the steady, stable, oddball Moomin family, there exists a paradox. “‘Flee!’ cried Moominmamma,” when the police come looking for her son. “She didn’t know what her Moomintroll had done, but she was convinced that she approved of it.” The paradox? There is no such thing as safety; in our (abundant) ignorance, we’ll make mistakes, we’ll lose each other, we’ll never completely understand what’s happening; yet we are safe here, you are safe here, because I love you and you are mine.

From the March/April 2013 special issue of The Horn Book Magazine.

says

says

says

Add Comment :-

RELATED

RECOMMENDED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.